How can we interrogate the memorials and markers from our past to better understand our history?

Elsewhere in the Te Akomanga we discussed how the impact of the ‘Black Lives Matter’ of 2020 prompted debate as to the ongoing relevance of our historical monuments and statues. The question was asked whether the time had come to have a serious conversation about the markers from our colonial past. As we move towards the compulsory teaching of New Zealand history in 2022, Tony Ballantyne from Otago University reminds us that colonisation is the ‘central fact of New Zealand history and cultural life’; it must be prominent in what is taught. Katie Pickles, Professor of History at the University of Canterbury, highlighted how ‘removing monuments to an imperial past is not the same for former colonies as it is for former empires’. Such action ‘drills to the very bedrock of colonial history. It shakes the imperial foundations’.

Giacomo Lichtner of Victoria University contends that now is not the time for such a conversation, but a rare opportunity for action. He compared this to how in the days after the Christchurch mosque attacks, it was not a time to discuss weapons, but a time to ban them. Lichtner maintained that confronting the ongoing hurt these statues still cause is the ‘responsibility of the descendants of those who erected them, not those who suffer because of them.’ In deciding what should be kept and what should go, communities should be guided by tangata whenua and mana whenua. For Lichtner, the idea that statues are there to ‘teach history, or that tearing them down is the prelude to burning books’, is lazy. ‘Statues do not teach; teachers teach.’

Armistice Centenary National Ceremony at Pukeahu National War Memorial, November 2018.

In our education programme at Pukeahu National War Memorial Park, we recognise the value of the site as a transformative space where teachers and educators can explore with students a range of perspectives, and challenge and extend the way they think. As with the debate about ‘statues and memorials from a racist past’, it must be recognised that commemoration is contested. People have different values about such matters, which are often about more than the commemoration of war. We frequently ask visitors to Pukeahu to consider ‘whose voices, values, and experiences are missing here?’

Pukeahu, like many of the monuments called into question in recent times, is inherently ‘perspective-laden’ and therefore controversial. If we accept that ‘controversy is essential to democratic life’, then we need knowledgeable, articulate and politically engaged citizens. We can help meet the goal of the New Zealand Curriculum that students become ‘critical, informed, and responsible citizens.’

A framework developed to support learning at Pukeahu can easily be adapted to provide a guide on how to interrogate other monuments and memorials from our past. This guide helps students to use the site to develop historical thinking skills. Students need to be encouraged to think of such objects as sites of analysis, places with multiple layers of history that need to be peeled back and critically interpreted, not merely accepted.

Historical monuments represent particular views of a community’s past and present. They can convey a sense of who or what is important or not. They are, typically, an expression of the perspectives of the politically, socially and economically powerful. They can impose a sense of who were the aggressors and who were the victims, the victors and the defeated, or more crudely – the ‘Good Guys and the Bad Guys’.

Manatū Taonga Ministry for Culture and Heritage

Matawhero memorial, near Gisborne, 2016.

The Matawhero memorial just outside Gisborne, with its inscription dedicated to ‘the memory of those massacred by Te Kooti’ in 1868, immediately conveys such a simple sense of right and wrong in understanding what occurred there through the emotive word ‘massacred’.

There is nothing new about the desire to pull down such monuments or move them out of sight. Many revolutions or regime changes have seen people act as though destruction of a monument exorcises its power and its ‘removal banishes the power from their midst.’ The Incas removed icons of conquered peoples’ gods, keeping them in a temple in their capital, Cuzco. The post-Soviet Russian government removed many statues of Lenin and others and relocated them in Muzeon Arts Park in Moscow. It would be interesting to consider the response in New Zealand to the idea of creating a public park where we could deposit what might be seen as symbols of racism.

New Zealand historian Ewan Morris, in a blog entitled Controversial monuments: doing the maths, suggests that when it comes to thinking about such monuments it is a case of applying the ‘language of basic arithmetic’: addition, subtraction, multiplication and division. Morris contends that when historical monuments come under attack, it is easy to accuse the monuments’ critics of stirring up division. It could be argued that debates over statues and other memorials reveal divisions that already exist within communities or as Morris contends, ‘divisiveness, is built into the landscape’.

Removing or subtracting contentious monuments from public places, ‘on the grounds that they celebrate past oppression and so help to entrench injustice in the present’ is, in many respects the simple approach. We saw this here with the removal of the statue to Captain John Hamilton from the CBD of the city named after him. In July 2021 statues of Queen Victoria and Elizabeth II were toppled in Canada as part of protests at the treatment of Indigenous children in residential schools. Between 1828 and 1997, at least 150,000 Indigenous children were taken from their families to attend these schools. This was a deliberate policy aimed at forcefully assimilating indigenous children into Canadian society. The recent discovery of 182 human remains in unmarked graves at a former residential school — the latest in a series of grim discoveries that have shocked the country – saw an outpouring of anger that included action against monuments to the two monarchs who were head of state during the time of this policy. Morris, and others, while perhaps understanding the sense of anger and outrage, questions such an approach, as destroying evidence is not the historian’s mission – and nor is ‘sanitising the past’.

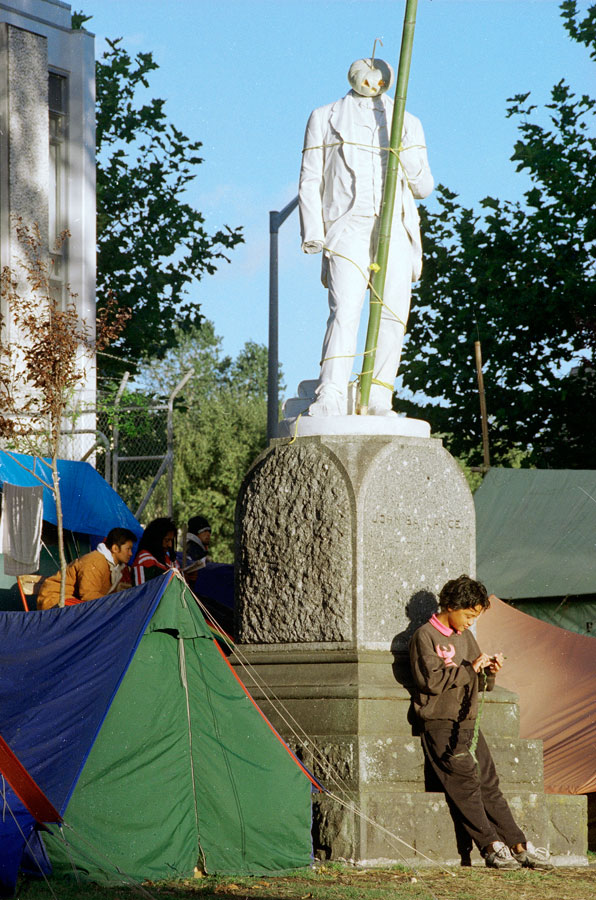

Alexander Turnbull Library, EP/1995/0789/15a

Beheaded statue of John Ballance during Moutoa Gardens (Pākaitore) occupation, Whanganui, 1995.

Another example of subtraction, with a little creative addition thrown in for good measure, can be found with the statue of John Ballance, a local MP and ex-premier of New Zealand (1891-93), which had stood in Moutoa Gardens (Pākaitore). During the 79-day occupation of the gardens by Te Rūnanga Pākaitore in 1995, the statue was beheaded. Ballance was blamed for policies that had led to the loss of Māori land. The missing head was replaced by a pumpkin. The body was also removed from its plinth and neither head nor body were ever recovered. A new bronze statue of Ballance was unveiled outside Whanganui’s civic centre in 2009.

If attitudes and historical scholarship have moved on since a memorial was created, why not add to the existing text and imagery? A new plaque on the memorial itself or an information board nearby could provide missing context and new information, including alternative perspectives on the past. This could also be achieved digitally, allowing for ‘new layers of interpretation without destroying the old ones’. While subtraction might seem the easiest response, addition seems to have gained favour recently with a number of people.

Alternatively, Morris wonders if we could think about multiplication, ‘creating new works of public art that tell different stories from those represented by older memorials.’ What these new memorials might look like would be an interesting task to set a class. At Pukeahu National War Memorial we frequently employ this approach, asking visitors, ‘if the National War Memorial fell down tomorrow, would we rebuild it and if so, what would it look like?’

Leonie Hayden, writing in the Spinoff, also considered Morris’ multiplication approach, suggesting that it was time to ‘Put up more statues – of New Zealanders who deserve them’, just as settler governments had in the late 1800s. She also wondered if a little ‘subtraction was in order’ by ‘maybe taking some of the stink ones down.’ Recent examples of multiplication can be seen in the approach of Te Tairāwhiti iwi to the Tuia 250 commemorations of 2019, which acknowledged the first onshore meetings between Māori and Europeans. Puhi Kai Iti, the site of Cook’s landing in 1769, now tells the story of that encounter from an iwi perspective and acknowledges the history of the site as a landing place for the Horouta and Te Ikaroa-a-Rauru waka. Iwi-led and designed public monuments now honour Ngāti Oneone ancestors such as the expert navigator Maia and Te Maro, who was killed in the first encounter with Cook’s crew.

In July 2020, speaking as part of a panel discussing ‘Memorials, names and ethical remembering’ (the full panel discussion can be found here), Morris suggested a series of questions to pose when considering whether to remove a memorial:

- Does the memorial represent someone responsible for crimes against humanity?

- What was the purpose of and context for the memorial’s creation?

- Are the inscriptions or imagery offensive?

- Is the location of the memorial problematic?

- Does the memorial dominate the landscape?

- Has the memorial become a rallying point for hate?

- Does the memorial cause significant offence to a substantial number of people?

Mark Hatlie, in Deconstructing Historical Markers, looks at how to ask questions of historical places, monuments, memorials and museums. These are ‘created sites of historical memory’ where people encounter constructed reminders of past events, usually tragedies, that in many cases still serve their original function. Hatlie explores how ‘historical markers create a link between three different situations’: the event or person to which the marker refers; the building of the marker itself; and the ‘now – you standing in front of the marker and “learning” from it. All three of these layers or situations have a wider context which is important for the monument.’

Hatlie advises the visitor to a historical marker such as a memorial to question it and not accept, passively and perhaps without even being aware of it, some intended or unintended ‘message’ offered by that marker. The monument’s builder had an intent which we should question. These markers occupy ‘overlapping and complex places in history, not just places in public space.’ They become most interesting when we actively consider that space.

Local researcher and teacher Michael Harcourt, who developed the framework to support learning at Pukeahu, suggests another set of criteria for interrogating such places or memorials to determine their geographical significance. These criteria are:

- Power – Is it a place which reveals power relations in society? Its meaning for some people might have been silenced or marginalised in the past. Perhaps some people felt or continue to feel a sense of belonging there, while others feel excluded.

- Legendary – The place or monument is ‘storied’. People tell legends there and it is used to sustain myths.

- Affected by change – How has the place or memorial changed over time, whether physically or in terms of how it is used or viewed?

- Contested and connected – Was this place or monument argued over? Is it still a source of debate? People may feel a strong sense of connection to it, often for different reasons.

- Evocative – The place or monument is one where you can ‘feel’ history.

Whatever strategy you employ, consider how visiting such sites – whether they be monuments or street names - can be an opportunity not only to examine an important aspect of our past, but to develop historical thinking skills around perspectives – and to also, as Hatlie puts it, ‘engage the monument in a dialogue’.

Steve Watters, Senior Historian-Educator, 2020

Community contributions