Ruapekapeka (1845)

Last battle of the Northern War

Tensions increased after Governor William Hobson’s transfer of the capital to Auckland in 1841 and an Australian depression created an economic recession in the Bay of Islands. Ngāpuhi resentment manifested itself most dramatically in July 1844 when the highly symbolic flagstaff above Kororāreka was felled. Three more times, in January and March 1845, Ngāti Rāhiri leader Hōne Heke Pōkai sent the Union Flag tumbling down, precipitating the First, or Northern, New Zealand War.

Soon more than flagstaffs were falling. After Heke and his ally Kawiti sacked Kororāreka in March 1845 the British reinforced their units and deployed Ngāpuhi allies led by Tāmati Wāka Nene. The Royal Navy easily controlled the seas, but it took longer to tackle Heke and Kawiti on the ground. Each side had to learn rapidly and each made mistakes in the battles of Puketutu (May 1845) and Ōhaeawai (July), the former a marginal British victory, the latter a bloody defeat.

The final battle was at Ruapekapeka, the Bat’s Nest. Like Ōhaeawai, Ruapekapeka was a new type of pā, designed to counter bombardment. Late last century, historian James Belich made much of these artillery-proof pā, in which underground bunkers, communications tunnels and rifle pits replaced palisades and fighting towers as the key defensive measures. He credited northern Māori with inventing trench warfare. Perhaps. Māori had certainly adapted pā to suit the musket, but others dismissed Belich’s claim as baseless post-colonial revisionism.

Conservator Fergus Clunie offered a third explanation. Buried like a musket ball in a footnote in Hugh Carleton’s 1877 book The Life of Henry Williams, Archdeacon of Waimate is a reference to the recent death of ‘Tapara, a native of the East Indies’, a non-European ‘Pakeha Maori’. ‘It was he who drew the lines of the fortified pas, the scientific tracing of which caused so much surprise’, Carleton commented. If Tapara had acquired ‘the rudiments of Hon. East India Co. fortification techniques’, Clunie speculated, it might have given him ‘an irresistible opportunity [decades later but no less the sweeter for it] to give the sahibs a goodly kick in the balls for old times’ sake’.

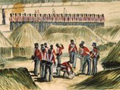

Whatever the engineering inspiration – and the debate is far from over – we can say with certainty that the next round of ball-breaking took place at Ruapekapeka, about 10 km inland from naval gunfire, atop a broad ridge in densely forested land. Designed to lure government forces, it had no strategic value and simply formed the nexus of a killing field. Behind a heavy wooden palisade of 7-m puriri trunks embedded almost 3 m in the ground was a warren of spaced rifle pits and bomb shelters, deep pits roofed over with timber and earth.

On 10 January 1846, while the new Governor George Grey watched, Colonel Henry Despard’s guns began battering the site, huge 32-pounders rocking the earth, a lighter 18-pounder and several 12-pounder howitzers and Congreve rockets adding to Kawiti’s misery. By next morning part of the defences had been breached and most of the defenders melted away, allowing the British and allied Māori forces under Nene to storm in.

Why? Old yarn-spinners had the defenders out in the bush, observing the Sabbath, but more likely this was (1) a ruse to lure the British to where they were more vulnerable, (2) a ploy to protect the evacuation of their wounded, or (3) a belief that they had wasted enough time taunting the redcoats.

Shortly afterwards Kawiti, Heke and Nene came to an accommodation. Grey, the arch spin-doctor, revoked martial law and pardoned everyone, ending the Northern War. Taking a part-deserted pā was not the Boy’s Own triumph Grey tried to make it, but nor are revisionist attempts to portray the Northern War as a Māori victory. Bay Māori never again took up arms against the Crown. Historian Matthew Wright observes that ‘it was as much a Ngā Puhi war as it was British. Nene’s forces stood across Heke’s key resource areas, and both Nene and the British were able to continue the war after Ruapekapeka, whereas Heke and Kawiti were forced to a halt.’

DOC manages Ruapekapeka, which is remarkably well preserved, enabling visitors to inspect both the pā and the British forward position about 300 m to the north. Local sensitivities made interpreting the site a minor battle in itself, but there is now an extensive set of signboards and markers.

Further information

This site is item number 17 on the History of New Zealand in 100 Places list.

Websites

- DOC information

- Northern War – NZ History

- Ruapekapeka Roadside Story (video)

- Biographies of Kawiti, George Grey, Henry Despard and Tāmati Wāka Nene - Te Ara

Books

- James Belich, The New Zealand Wars and the Victorian interpretation of racial conflict, Auckland University Press, Auckland, 1986

- Matthew Wright, Two peoples, one land: the New Zealand Wars, Reed Books, Auckland, 2006

Community contributions