New Zealand’s path to Gallipoli began with the outbreak of war between the United Kingdom and Germany in August 1914. Prime Minister William Massey pledged New Zealand’s support as part of the British Empire and set about raising a military force for service overseas. The 8454-strong New Zealand Expeditionary Force (NZEF) left Wellington in October 1914, and after linking up with the Australian Imperial Force (AIF) steamed in convoy across the Indian Ocean, expecting to join British forces fighting on the Western Front.

In early November 1914, the Ottoman Empire entered the war on the side of the Central Powers (Germany, Austria-Hungary and Bulgaria). This changed the strategic situation, especially in the Middle East, where Ottoman forces now posed a direct threat to the Suez Canal – an important British shipping lane between Europe and Asia. The British authorities decided to offload the Australian and New Zealand expeditionary forces in Egypt to complete their training and bolster the British forces guarding the canal. In February 1915, elements of the NZEF helped fight off an Ottoman raid on the Suez Canal.

Gallipoli invasion

The NZEF’s wait in Egypt ended in early April 1915, when it was transported to the Greek island of Lemnos to prepare for the invasion of the Gallipoli Peninsula. The peninsula was important because it guarded the entrance to the Dardanelles Strait – a strategic waterway leading to the Sea of Marmara and, via the Bosphorus, the Black Sea. The Allied plan was to break through the straits, capture the Ottoman capital, Constantinople (now Istanbul), and knock the Ottoman Empire out of the war. Access to the straits and the Sea of Marmara would also provide the Allies with a supply line to Russia, and open up new areas in which to attack the Central Powers.

Following the failure of British and French warships to ‘force’ the straits, the Allies dispatched the Mediterranean Expeditionary Force (MEF) to capture the Gallipoli Peninsula. New Zealanders and Australians made up nearly half of the MEF’s 75,000 troops; the rest were from Great Britain and Ireland, France, India and Newfoundland.

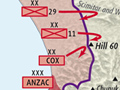

Led by Lieutenant-General Sir Ian Hamilton, the MEF launched its invasion of the Dardanelles on 25 April 1915. While British (and later French) troops made the main landing at Cape Helles on the southern tip of the peninsula, Lieutenant-General Sir William Birdwood’s Australian and New Zealand Army Corps (ANZAC) – soon to become known as Anzacs – made a diversionary attack 20 km to the north at Gaba Tepe (Kabatepe). Because of navigational errors the Anzacs landed about 2 km north of the intended site. Instead of a flat stretch of coastline, they came ashore at Anzac Cove, a narrow beach overlooked by steep hills and ridgelines. The New Zealanders, who were part of the New Zealand and Australian Division, followed the Australians in and took up positions in the northern part of the Anzac sector. Read more about the Gallipoli invasion.

Stalemate

The landings never came close to achieving their goals. Although the Allies managed to secure footholds on the peninsula, the fighting quickly degenerated into trench warfare, with the Anzacs holding a tenuous perimeter against strong Ottoman attacks. The troops endured heat, flies, the stench of unburied bodies, insufficient water and disease.

Early in May 1915, the New Zealand Infantry Brigade was ferried south to Helles, where it took part in an assault on the village of Krithia (now Alchiteppe) on 8 May. The attack was a complete disaster; the New Zealanders suffered more than 800 casualties but achieved nothing. Read more about the Gallipoli stalemate.

August offensive and Chunuk Bair

In August 1915, the Allies launched a major offensive in an attempt to break the deadlock. The plan was to capture the high ground overlooking the Anzac sector, the Sari Bair Range, while a British force landed further north at Suvla Bay. Major-General Sir Alexander Godley’s New Zealand and Australian Division played a prominent part in this offensive, with New Zealand troops capturing one of the hills, Chunuk Bair. This was the limit of the Allied advance; an Ottoman counter-attack forced the troops who had relieved the New Zealanders off Chunuk Bair, while the British failed to make any progress inland from Suvla.

In the aftermath of the Sari Bair offensive, the Allies tried to break through the Ottoman line north of Anzac, which was now linked up with the beachhead at Suvla. New Zealanders were also involved in this fighting, participating in costly attacks at Hill 60 in late August. Read more about the Sari Bair offensive.

Evacuation

Hill 60 turned out to be the last major Allied attack at Gallipoli. The failure of the August battles meant a return to stalemate. In mid-September 1915, the exhausted New Zealand infantry and mounted rifles were briefly withdrawn to Lemnos to rest and receive reinforcements from Egypt.

By the time the New Zealanders returned to Anzac in November, the future of the campaign had been determined. Following the failure of the August offensive, the British government began questioning the value of persisting at Gallipoli, especially given the need for troops on the Western Front and at Salonika in northern Greece, where Allied forces were supporting Serbia against the Central Powers. In October, the British replaced Hamilton as commander-in-chief of the MEF. His successor, Lieutenant-General Sir Charles C. Monro, quickly proposed evacuation.

On 22 November the British decided to cut their losses and evacuate Suvla and Anzac. In contrast to earlier operations, planning moved quickly and efficiently. The evacuation of Anzac began on 15 December, with 36,000 troops withdrawn over the following five nights. The last party left in the early hours of 20 December, the night of the last evacuation from Suvla. British and French forces remained at Helles until 8-9 January 1916. Read more about the evacuation.

Aftermath

Gallipoli was a costly failure for the Allies: 44,000 Allied soldiers died, including more than 8700 Australians. Among the dead were 2779 New Zealanders – about a sixth of those who fought on the peninsula. Victory came at a high price for the Ottoman Empire, which lost 87,000 men during the campaign.

Shortly after the October 1918 armistice with the Ottoman Empire, British and dominion Graves Registration units landed on Gallipoli and began building permanent cemeteries for the dead of 1915-1916. During the 1920s, the Imperial War Graves Commission (now the Commonwealth War Graves Commission) completed a network of Anzac and British cemeteries and memorials to the missing that still exist on the peninsula today. In 1925, the New Zealand government unveiled a New Zealand battlefield memorial on the summit of Chunuk Bair. The battlefields are now part of the 33,000-ha Gallipoli Peninsula Historical National Park, or Peace Park.

Legacy

The Gallipoli campaign was a relatively minor aspect of the First World War. The number of dead, although horrific, pales in comparison with the casualties on the Western Front in France and Belgium. Nevertheless, for New Zealand, along with Australia and Turkey, it has great significance.

In Turkey, the campaign marked the beginning of a national revival. The Ottoman hero of Gallipoli, Mustafa Kemal, would eventually become, as Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, the founding President of the Turkish Republic. In New Zealand (and Australia), Gallipoli helped foster a developing sense of national identity. Those at home were proud of how their men had performed on the world stage, establishing a reputation for fighting hard in difficult conditions.

Anzac Day grew out of this pride. First observed on 25 April 1916, the date of the landing has become a crucial part of the fabric of national life – a time for remembering not only those who died at Gallipoli, but all New Zealanders who have served their country in times of war and peace.