On the afternoon of 19 November 2010, an explosion ripped through the remote Pike River mine on the West Coast of the South Island, killing 29 men. Their bodies have not been recovered, and remain in the mine.

Underground coal mining has always been a dangerous occupation. In addition to the risk of asphyxiation and the danger of falling coal, there is the threat of an explosion of methane gas, which is continuously expelled by coal seams and becomes potentially explosive when mixed with air. Mines must have good ventilation to prevent methane building up.

Major mining disasters

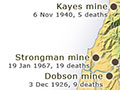

Pike River is the latest major New Zealand mining disaster. Previous mass mining tragedies include:

Kaitangata mine, South Otago:

21 February 1879, 34 dead

Brunner mine, West Coast:

26 March 1896, 65 dead

Ralph's mine, Huntly:

12 September 1914, 43 dead

Dobson mine, West Coast:

3 December 1926, 9 dead

Glen Afton mine, Huntly:

24 September 1939, 11 dead

Strongman mine, West Coast:

19 January 1967, 19 dead

Read more on the New Zealand disasters timeline.

Since coal mining began in New Zealand, there have been 211 recorded deaths from nine separate explosions, the most recent at the Pike River mine. Although the coal company’s management believed that their mining methods, using modern technology, were both safer and more efficient than those used in the past, the explosion on 19 November 2010 bore a tragic resemblance to previous coal-mine explosions.

The report of the subsequent Royal Commission of Inquiry revealed a combination of errors within the mine, including inadequate methane drainage, non-functioning gas sensors, flawed electrical and ventilation design, and inaction on hazard warnings. These failings were compounded by the failure of government regulatory authorities to effectively inspect the mine and act to remedy the problems.

This article marks the fifth anniversary of the explosion at the Pike River mine. The human tragedy cannot be undone, but it is hoped that documenting the events leading up to the disaster will help future generations to avoid making similar mistakes. These events are recorded in the report of the Royal Commission and in a book by investigative journalist Rebecca Macfie, Tragedy at Pike River mine: how and why 29 men died.

The path to a coal mine

Coal at the top of a mountain

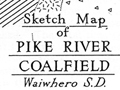

Harold Wellman made the first geological examination of coal seams near the crest of the Paparoa Range, from which the Pike Stream flows into the Grey Valley, in 1946-47. [1]

Wellman recognised that there was a large resource of bituminous coal in these seams, which were exposed along a steep escarpment in the headwaters of the Punakaiki River that extended east to the Hawera Fault. He had previously examined coalfields all over the West Coast, and was struck by the fact that the highest-grade coal was found at high elevation — an unusual situation, because the formation of high-grade coal requires deep burial.

In his report on the Pike River coalfield, Wellman developed the idea that West Coast coalfields had a two-stage history: maximum burial in small basins about 35 million years ago, then later uplift to form the present mountains. This had important practical implications, because the later uplift phase was responsible for much of the faulting and fracturing that complicates underground mining on the West Coast.

The exploration phase

Because of its remoteness and the low price of coal, there was little interest in the Pike River coalfield for the next 30 years. The government-owned State Coal Mines held mining and prospecting leases over all the major coalfields except Pike River. In 1979, geologist Terry Bates and assistants explored the area. Six drill holes confirmed the presence of a large area of coal. The Pike River Coal Company was formed in 1982 to hold exploration rights; in 1988 the company was bought by New Zealand Oil and Gas Ltd.

When Paparoa National Park was created in 1987, the area of the Pike River coalfield was deliberately excluded from it. The permission of the Department of Conservation was, however, required for access and other activities outside the boundaries of the coalfield.

Over a 13-year period, the Pike River Coal Company undertook further exploration and acquired the necessary authorisations to develop a mine, including a mining permit, an access arrangement and resource consents.

Decision to open a mine

From the mid-1980s, there was a growing overseas market for West Coast coking coal — more than 1 million tonnes was exported in 1994, and more than double that in 2002. The high-quality coal commanded a good price because it was in demand for specialised metallurgical use. The board of New Zealand Oil and Gas decided that the time was right to open a mine. Initially they intended to develop the mine in partnership with an established mining company, but those they approached considered the venture too risky. So it was decided that the Pike River Coal Company should undertake the mining venture itself.

At that stage no one in the company had any expertise or experience in coal mining. Gordon Ward, the managing director, was an accountant and financier. Everything the company did had to be designed from scratch or purchased. Peter Whittall, a mining engineer with 24 years’ experience with Australian mining giant BHP, was appointed technical manager in 2005. Starting with an empty office in Greymouth, he had the task of creating a working coal mine.

The public image

From the outset, Pike River Coal mounted a vigorous public relations campaign to persuade investors, politicians and West Coast residents that the mine would surpass any seen previously in New Zealand. Speaking to a mining conference in 2006, Whittall cast its lack of experience as an advantage:

Pike will not have the shackles of past operational and management errors at the mine; it has a clean sheet to plan, design, construct and operate the mine with state-of-the-art technical and management systems; the opportunity to recruit and develop a workforce with aligned goals for the project’s success; and to achieve benchmark environmental standards for an underground operation. [2]

The construction phase

Final approval of the concept

In July 2005, a joint report by Ward and Whittall to the board of Pike River Coal proposed a plan and development strategy for the mine.

DoC requirements

During the construction phase, it was often stated that Department of Conservation (DoC) requirements and restrictions resulted in extra costs and delays. Evidence to the Royal Commission, however, showed that DoC had agreed to every request made by the mining company over several years.

Largely based on earlier consultants’ reports, this envisaged an ambitious project involving the construction of an access road across steep, bush-covered hillsides to the mine entrance. From there a 2.3-km tunnel would be driven uphill at an angle of approximately 5° through solid rock until it crossed the Hawera Fault and penetrated the coal seam. Only then could mine development and coal production begin. Targets were set for the completion of each phase; both road and tunnel would be completed by September 2006.

In practice, almost every phase of construction was dogged by delays and cost overruns. Most of the problems resulted from the failure of the company to undertake adequate geological and geotechnical investigations before starting work. New Zealand rock formations are often more deformed and broken than those in Australia, and the company seemed to be largely oblivious to the potential problems.

Construction problems

Work on the 11-km access road, which involved building several bridges, began in December 2005. The final, steep section to the mine portal included taking the road around a steep, gorgy part of Pike Stream, across a mixture of jointed hard rock and landslide debris. [3] Considering the difficulties, it was remarkable that the road was completed in 10 months. Work on the 2.3-km tunnel through stone could then begin.

The company’s assumption that it would be tunnelling through strong rock that would require little support proved to be misguided. Nearly 80% of the tunnel passed through broken rock that required costly bolting, mesh-covering and concreting. Building the tunnel took twice as long as anticipated, and cost more than twice the amount budgeted. The tunnel crossed the Hawera Fault into coal in November 2008, and on the 27th the mine was officially opened to mark the imminent start of coal production.

Ventilation

A major ventilation shaft was sunk close to the Hawera Fault in late 2008. [4] [5] Powered by a large fan, this was designed to extract methane-rich gas from the mine and draw in fresh air along the tunnel. Mining could not begin until the ventilation system was working. In February 2009, however, the bottom part of the shaft collapsed and filled with fallen rock. The company decided to abandon the collapsed section and construct a new bypass shaft.

The original plan was to install the ventilation fan at the top of the shaft. Because of operational difficulties, it was decided to re-site the fan within the mine at the bottom of the shaft. This was not normal industry practice as it made the ventilation system vulnerable to power failure, fire or explosion.

Although adequate ventilation is critical to the safe running of a coal mine, the Pike River mine did not have a dedicated ventilation officer — this was one of the many responsibilities of the mine manager. The appointment of a ventilation officer is a statutory requirement in Australia and most other countries with a coal-mining industry, but it was not a requirement in New Zealand.

Preparing for coal mining

Hydro-mining

At the planning stage, it had been agreed that coal would be extracted by a combination of coal-cutting machinery and hydro-mining — a system that uses a high-pressure water jet to carve out the coal seam and wash it downhill to storage facilities. Hydro-mining had been used effectively elsewhere on the West Coast, but did pose problems. In particular, collapse of the coal face could cause large and unpredictable methane pulses in the mine.

The coal-cutting machines initially obtained for the mine kept breaking down in the rugged conditions. More worryingly, they also sparked small methane explosions when the cutting tool hit hard sandstone.

Ongoing problems

Although coal was being extracted from the Pike River mine from November 2010, it was still in start-up mode and considerably behind schedule. Costs blew out because of the problems with the ventilation and hydro-mining systems, and machinery breakdowns. The company needed to go back to its investors and other lenders for more funds. Because of the continuing delays, the board dismissed Gordon Ward, the general manager, in mid-2010 and replaced him with Peter Whittall.

By 2010, there was ample evidence of dysfunction at senior management level at the mine. Six different people held the statutory position of mine manager in 2009-2010, and there was a very high turnover of experienced technical staff.

Methane hazard

While the mine management was dealing with a range of problems, the methane hazard was largely overlooked.

Safety issues

Many catastrophic mining accidents are preceded by situations in which warning signs are normalised, dismissed as intermittent or simply ignored. At Pike, however, a lot of safety information was not assessed at all. It simply remained unnoticed in the safety management system. [6]

From the time the tunnel penetrated coal there had been frequent alarms about methane levels and many small ignitions, but these warning signals were often not acted on because of the pressure to increase coal production. The planned methane detection system was never fully installed or calibrated.

At one stage the Inspector of Mines, employed by the Labour Department, considered closing down the mine until the methane and ventilation problems were sorted out, but the mine management convinced him that they had these issues under control.

The explosion

On the afternoon of Friday 19 November, men employed by the Pike River mine were underground alongside employees of five different contracting companies. As on any workday, men entered and left the mine at different times. Chance played a big part in deciding the 31 men who were underground at 3.44 p.m. when an explosion disabled power and communication into the mine.

Daniel Rockhouse was refilling his loader in the tunnel when he was blown off his feet by the explosion. He soon lost consciousness. When he came to in the smoky atmosphere, Rockhouse groped his way down the tunnel in darkness. After about 300 m he found Russell Smith on the ground, and together they struggled to the mine entrance, with Rockhouse holding Smith up and grasping a rail for support with his free hand. Both were suffering from carbon monoxide poisoning, and they were the only survivors. The other 29 men in the mine were either killed by the force of the explosion or suffocated by noxious gases.

CCTV footage showed a pressure wave and flying debris blasted out of the mine entrance. A subsequent inspection by helicopter found that the back-up fan at the top of the ventilation shaft was badly damaged and the surrounding vegetation charred.

The immediate aftermath

Over the next three days, there was confusion about the possibility of re-entering the mine. The last major underground mine explosion, at Strongman mine, had occurred more than 40 years earlier and there was little experience of dealing with this type of incident. It was apparent to those with experience of coal mining that the men left in the mine could not have survived, but there was public pressure to attempt a re-entry. The highly publicised rescue of 33 men trapped underground in a Chilean copper mine a few months earlier raised false hopes that a rescue mission might be feasible.

Further explosions on 24, 26 and 28 November made it clear that it would be too dangerous to attempt re-entry, and the mine was subsequently sealed.

Remembering the Pike River 29

A public memorial service for the 29 men killed was held at Omoto racecourse, near Greymouth, on 2 December 2010. A permanent memorial, listing the names of the men killed, has been erected near the junction of Atarau Road and the road up to the mine and a memorial stone was unveiled in Greymouth on 19 November 2011.

In 2013, the Orpheus Choir of Wellington commissioned Dave Dobbyn to write a piece dedicated to the men who died in the disaster. In writing This love, Dobbyn chose to focus on the love and memories of the families rather than evoke the events leading up to the disaster.

A group representing the families of those killed in the 2010 explosion proposed that the Pike River mine site and surrounding area be added to the Paparoa National Park, with a designated Great Walk established between the mine and Punakaiki. This proposal was accepted and a three-year project to complete a Great Walk between Blackball and Punakaiki, with a side track to the mine, was announced by Environment Minister Nick Smith on 15 November 2015.

Lessons from Pike River

Soon after the explosion, a Royal Commission was established to examine the circumstances that had led to the tragedy. In 2012, the Commission produced a comprehensive report that identified both the immediate cause of the explosion and the longer-term factors leading up to it.

Immediate cause of the explosion

The Commission’s report has a chilling similarity to the reports of enquiries into the previous eight coal mine explosions in which men were killed. In each case, the mine’s management had overlooked or played down the risk of a methane explosion.

There is little doubt that the first explosion on 19 November was caused by the ignition of a large volume of methane. The Brunner coal seam had long been known to be highly gassy, and there had been many small ignitions during 2009-2010. Managers under pressure to increase coal production in the face of a financial crisis had overlooked safety issues. With no access to the mine the precise location of the explosion remains uncertain, so the Commission was only able to suggest possibilities.

Design of the Pike River mine

The project to mine coal at Pike River was flawed from the start. The vision of driving a 2.3-km tunnel uphill though solid rock, across a fault into a gassy coal seam, with no alternative tunnel or shaft for ventilation or exit, ignored international coal-mining experience. This was probably the only mine in the world in which the main ventilation fan was sited underground.

The plans for the mine received virtually no independent scrutiny because government authorities no longer had any responsibility to check that mine design was prudent or safe.

Failure of oversight

The report of the Royal Commission highlighted widespread, systemic problems in the mining industry. The specific issues at Pike River were exacerbated by inadequate oversight of the mine by regulatory organisations and deficiencies in the laws covering health and safety. Since 1992 the level of regulatory oversight had been progressively reduced, and by 2010 there were only two mine inspectors for the whole country.

The coal market collapses

In 2012 the international price of coking coal fell dramatically, leading to the closure of a number of coal mines. Solid Energy, New Zealand’s main exporter of coking coal, went into voluntary administration in 2013 and is currently being wound up. Had there been no explosion, it is likely that Pike River would have shut down by 2013 as there was no longer a market for the coal it was producing.

Under the heading, ‘A failure to learn’, the report noted that 'New Zealand’s health and safety record is inferior to that of other comparable countries. The rate of workplace fatalities is higher than in the United Kingdom, Australia and Canada, worse than the OECD average and has remained static in recent years'. [7]

After the Commission’s report was released in November 2012, Prime Minister John Key publicly apologised for the shortcomings that had been revealed. [8] In a letter to the families of the victims, he wrote, 'On behalf of the Government, I want to reiterate my apology to the families, friends and loved ones of the deceased men for the role this lack of regulatory effectiveness played in the tragedy'.

Following recommendations from the Royal Commission, the government established WorkSafe New Zealand, a Crown Agency dedicated to safety, with an independent board.

Legal action

After the Royal Commission completed its report, the Department of Labour laid charges against the Pike River coal company under the existing Health and Safety in Employment Act. The company, then under the control of receivers, did not appear at the hearing. In finding the company guilty, Judge Jane Farish commented on 'a systematic failure of the company to implement and audit its own (inadequate) safety plans and procedures'.[9]

Subsequently, in December 2014, charges against Peter Whittall under existing health and safety legislation were dropped. It was agreed to pay the remaining funds from the Pike River Coal company ($3.41 million) to the families rather than proceed with legal action.

Later developments

In 2014 the National-led government accepted a decision by Solid Energy, the new owners of the mine, that ‘potentially fatal risk factors’ made it too dangerous to re-enter it and attempt to recover the bodies. The Labour-led government which took office in 2017 reversed this decision. The Pike River Recovery Agency recovered the tunnel as far as the roof fall at the end of the drift in February 2021 at a cost of $51 million, more than double the original budget. No bodies were recovered and the access tunnel was sealed.

Further information

This web feature was written by Simon Nathan and produced by the NZHistory team.

Books

- Rebecca Macfie, Tragedy at Pike River mine, Awa Press, Wellington, 2013. More information on the Awa Press website.

- Paul Maunder, Coal and the Coast: a reflection on the Pike River disaster, Canterbury University Press, Christchurch, 2012

Links

- Royal Commission on the Pike River Coal Mine Tragedy report

- Coal and Coal Mining (Te Ara)

- Harold Wellman (Dictionary of New Zealand Biography)

- Commissions of inquiry (Te Ara)

Footnotes

[1] H.W. Wellman, ‘Geology of the Pike River coalfield, north Westland’, NZ Journal of Science & Technology B30(2), 1948, pp. 84-95.

[2] P. Whittall, ‘Pike River Coal – Hydraulic mine design on New Zealand’s West Coast’, Proceedings of the AusIMM (NZ Branch) conference, 2006, pp. 83-93.

[3] C. Anderson, D. Macfarlane and T. McMorran, ‘Development of the Pike River Mine Access Road’, Proceedings of the AusIMM (NZ Branch) conference, 2007, pp. 247-53.

[4] E. Giles, T. Moynihan and P. Whittall, ‘Pike River coal mine – No 1 shaft’, Proceedings of the AusIMM (NZ Branch) conference, 2009, pp. 157-67.

[5] J. Edwards and E. Giles, ‘Constructing a shaft top in near-Alpine conditions: Pike River coal mine #1 shaft’, Proceedings of the AusIMM (NZ Branch) conference, 2010, pp. 229-39.

[6] Royal Commission on the Pike River Coal Mine Tragedy, vol. 2, ch. 13, sn 15, p. 175.

[7] Royal Commission on the Pike River Coal Mine Tragedy, vol. 1, p. 15.

[8] NZ Herald, 'PM gives formal apology for Govt's contribution to Pike deaths' (Youtube)

[9] Judgement by Judge Farish, 13 May 2013.