New Zealand Federation of Women's Institutes

1921 –

Theme: Rural

Known as:

- Women's Institutes

1921 – 1952 - New Zealand Federation of Country Women's Institutes

1952 – 2004 - New Zealand Federation of Women's Institutes

2004 –

This essay written by Rosemarie Smith was first published in Women Together: a History of Women's Organisations in New Zealand in 1993. It was updated by Rosemarie Smith in 2018.

1921–1993

Up to the 1990s, the Federation of Country Women's Institutes (CWI) frequently claimed to have the largest membership of any women's organisation in New Zealand. Named the Women's Institutes (WI) until 1952, its aim was 'the improvement and development of community life' in rural areas, by bringing women together to discuss matters of mutual concern. [1] Membership was always firmly non-sectarian, non-party political, and open to all women of the community: 'All pay the same small subscription, have the same rights, the same responsibilities, the same privileges.' [2]

The WI began in Canada in 1897 as a grass-roots domestic education programme. Imported into Britain in 1915, it was given substantial state support in order to encourage women's productive role in agriculture and horticulture, and thus increase wartime food production. The emphasis was on village-based production of necessary goods and services, marketed through co-operatives.

The WI in New Zealand traced its origins to Anna Elizabeth (Bessie) Jerome Spencer's attendance at a WI craft exhibition in London in 1919. An avid craftswoman herself, she was 'deeply impressed', [3] and investigated the WI movement with a view to establishing it in New Zealand after her return from voluntary war service in Britain.

A former principal of Napier Girls' High School, Jerome Spencer was a woman of great physical and intellectual energy who had for some years been searching for a mission in life. Before the war she and her friend Amy Hutchinson (whom she later described as the 'spiritual founder' of the WI) [4] were involved in a progressive group with wide interests, based at Havelock North. Their interest in the WI probably reflected the goals of this group, which valued crafts not just for their usefulness, but as a means of developing the intellectual, cultural and spiritual potential of both the individual and society.

The first meeting of a Women's Institute in New Zealand was held at Hutchinson's home at Rissington, near Napier, in January 1921, with Jerome Spencer elected as president. The first annual report of the Rissington Institute provided a model for WI programmes until the 1990s: its list of activities included addresses, homecraft demonstrations, a gift afternoon, a public entertainment, a lantern lecture, an exhibition and a sale of produce. Although each institute was autonomous, there was considerable consensus over the years on programmes developed to suit members' interests. There was a strong emphasis on practical knowledge, thrift and self-sufficiency, and frequent competitions encouraged members to participate and to strive for excellence. Then as in the 1990s, the formula was, 'Something to see, something to hear, something to do', with the added injunction, ‘if you know a good thing, pass it on.' [5]

The movement spread slowly at first. By the first WI conference in 1925 there were six institutes, all in Hawke's Bay. Jerome Spencer, and later English WI organiser Agnes Stops, made extensive speaking tours around the country. Although the government refused Jerome Spencer's 1926 request for financial assistance to develop new institutes, farming newspapers began to promote the movement in their recently established women's pages. 'Tui' of The New Zealand Dairy Exporter told her readers that the WI would be a 'god-send' to them, [6] and the paper later financed one of Stops' tours. The New Zealand Farmer helped publish the WI newsletter; in 1927 it became the magazine Home and Country. In 1929 Mabel Christmas gave radio talks about WI on 2YA, beginning a relationship with local radio stations which was to last into the 1960s.

Jerome Spencer hoped the WI would train women to take their place in all aspects of New Zealand life, and from the outset there was an emphasis on learning correct meeting procedure. But the very broad programme outline, the initially fragmented nature of the movement, and its emphasis on local autonomy meant it was some time before a clear direction emerged. The pre-eminent concerns which developed were reflected in the organisation's educational, social and cultural programmes, although it also approached the government over the years on a wide range of issues affecting all women – in health, education, communications and justice.

The WI, in conjunction with the Women's Division of the New Zealand Farmers' Union and the adult education authorities of the day, brought adult education to the rural community. Major festivals of drama, choral singing and writing, and displays of domestic arts, became a regular part of rural life. Women were encouraged to develop their skills, though always within the limits of the acceptable female role of wife and mother.

Over the years WI women have worked together to generate a massive amount of goods, services and funds for numerous causes, both local and national. Major projects included the purchase in 1950 of WI's national headquarters in Wellington (known since 1959 as Jerome Spencer House), and the medical research scholarships awarded since 1971. In the 1980s, the CWI and the New Zealand Wool Board ran a joint project to teach primary schoolchildren to knit.

Alexander Turnbull Library, MNZ-0957-1/4-F.

Meeting of the first federation council of Women's Institutes at Rissington, Hawke's Bay, 1925. Bessie Jerome Spencer is seated centre front and Amy Hutchinson is standing second row, fourth from right.

The WI's structure, rules, badge and much of its character were adapted from the British model. Local institutes co-operated within provincial federations that were administered by an elected executive; Hawke's Bay was the first federation (1925), followed by Auckland (1927) and Wellington (1928). The first Dominion conference was held in Wellington in 1930, and the 1933 conference adopted the constitution of the Dominion Federation. Expansion was particularly rapid during the Depression years. Membership had reached 38,000 by 1964, in 1032 institutes and 52 federations. In 1992, there were 19,000 members in 740 institutes.

In the WI's efforts to include Māori women, a shared interest in crafts and the performing arts provided common ground. Māori women tended to belong to Māori Institutes, the first being Te Awapuni at Kohupātiki (1929). The WI was genuinely interested in Māori crafts, and its attempts to understand and assist assimilation were well-meaning. However, Māori women were rarely acknowledged by name in WI records, suggesting that social distance was maintained. There appears to have been a falling away of interest among Māori women, followed by a switch of allegiance to the Māori Women's Welfare League when this was formed in 1951.

The WI's international links were always important, especially those between individual institutes in New Zealand and Britain. The New Zealand WI was one of the first three members of the Associated Country Women of the World (ACWW), formed in 1933, and a major supporter of its development projects for women in the Third World.

The original aims and objects of the WI were specifically to increase opportunities and activities available to rural women and so reduce the allure of the town, in order that 'New Zealanders may continue to be a race of contented country dwellers'. [7] But although this aim was reaffirmed in 1952 when the Women's Institutes added 'Country' to their name, it was already being eroded by demographic change. That year the rule confining institutes to towns with populations under 4000 was changed to an upper limit of 6000; some towns with established institutes had already grown beyond that. Exceptions had also been made after 1931 for urban institutes catering for retired rural women.

The CWI's urban membership rose steadily, as more rural women moved to the towns and urban women clamoured for institutes of their own – despite the spread of Townswomen's Guilds, founded by Jerome Spencer in 1932. In the 1990s urban members outnumbered rural, and the 'Country' label was once again under discussion. Although CWI still asserted its particular mandate to speak for rural women, it was by then saying that 'Country' referred to the nation as a whole, not just to the rural community.

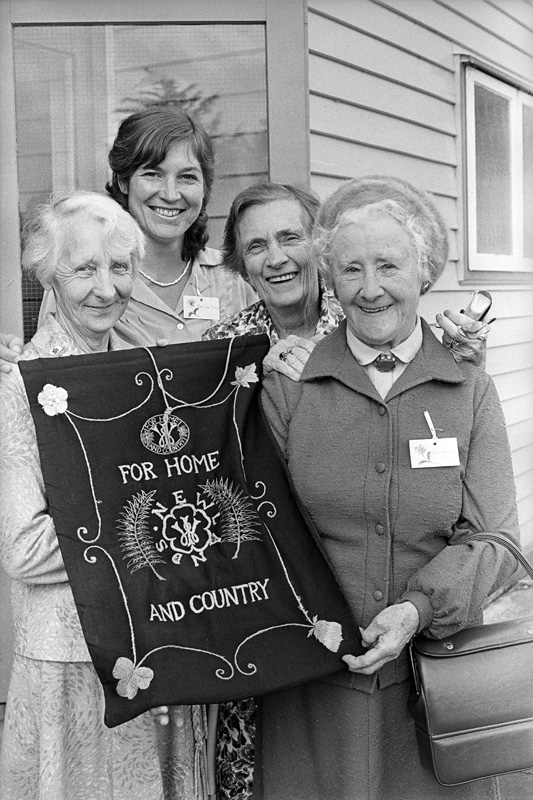

Alexander Turnbull Library, EP/1984/1220/22-F.

Members of the Newlands Country Women’s Institute display the original banner made by some of the first members, 1984.

The CWI engaged in controversial issues at times, for example campaigning against the ratification of CEDAW in 1984. When other rural pressure groups proposed a Ministry of Rural Affairs in 1991, CWI rejected this as potentially compromising and 'divisive', on the grounds that the ministry would cater for CWI's rural members at the expense of its large urban membership. [8]

In such debates, the CWI increasingly emphasised the size and spread of its membership, as it voiced the concerns of a large section of New Zealand women in the face of growing pressure for change from other, urban-based women's organisations. In 1986 it held a 'CWI Woman of the Year' competition to draw attention to the organisation and the calibre of its members. After 70 years of 'Homemaking, Co-operation, Citizenship', [9] the CWI continued to hold a powerful attraction as a meeting place for women where their identity as homemakers and caregivers was upheld and affirmed.

Rosemarie Smith

1994–2018

In the later 1990s, declining numbers and aging membership were already taking their toll, not least on CWI finances. Successive national executives and their advisors continued with strenuous efforts to effect more substantial change, exhorting members to recruit and institutes to publicise their work more effectively.

Avelda Howie, who in 1994 became the youngest national president to date, was adamant change was necessary. She spoke of CWI ‘conserv[ing] good values and principles … but to succeed as an organisation we must recognise and acknowledge change in women’s lives.’ [10] Despite hopes that Howie’s youth and sense of fun would be sufficient to coax members out of their comfort zones into a new era, two decades later 2014 national president Kay Hart was still discussing how to attract younger members while ‘maintaining our phenomenal tradition’. [11]

In 2004, the CWI finally dropped the ‘Country’ label it had inserted in 1952, once again becoming the New Zealand Federation of Women’s Institutes (WI). Unlike Rural Women New Zealand, it wished to promote a wider, more urban identity in the struggle for relevance – and survival. Marketing initiatives such as ’Women on the Move’ promotional brochures in 1999, ‘Feel Alive with CWI’ t-shirts in 2003 and Project Renew in 2006 (with a communications plan from public relations firm WHAM) all pushed for being more outward-looking and dynamic.

Slower than some other large organisations to enter the technological era, CWI computerised its national office in the 1990s, secured a domain name in 2003, began to update its very primitive website in 2005 and added a Facebook page in 2013. The effectiveness of the national magazine Home and Country had been impaired by low circulation numbers, and in 2018 planning began for change in its production and distribution.

One especially painful enforced change was the 2006 sale of Jerome Spencer House in Wellington, after modern earthquake codes, plus health and safety standards impinging on both guests and staff, made the necessary upgrading financially impractical. The loss of this convenient, inexpensive and woman-friendly accommodation in central Wellington was keenly felt by members. National executives had found it especially valuable to stay there together for meetings, and many members of Parliament had boarded there – a useful connection. WI bought an office in central Wellington in 2007, then in 2017 moved to Lower Hutt.

Meanwhile the organisation largely continued with business as usual, keeping its original motto, ‘For home and country’, and adopting in 2016 the vision statement: ‘To encourage and support all women within their communities’, offering friendship and fun, homemaking and craft skills, community involvement and training in meeting procedure. Despite their PR efforts, members felt that the modern WI was overlooked by the media, in which reports of backward-looking events such as anniversaries and long-service awards tended to dominate. For example:

[Mangawai Women’s Institute] follows the time-honoured traditions of other women’s institutes both here and overseas. Emphasis is given to traditional home skills such as baking, making of pickles and jams, crafts, flower and produce growing and presentation. There is a social and political focus too and recommendations are made to Central Government on issues of importance of the day. Above all, the women’s institute is a place where friendships are forged and a support network develops. [12]

‘Political work’ referred to remits resulting in letters to ministers and submissions to Parliament. At times these conveyed a view of modern society as a dangerous, morally degenerate place, for example in this submission supporting harsher penalties for young offenders: ‘Many of our young people, both male and female, have lost respect of our laws, and flout them constantly without redress. A stronger example is required.’ [13] In 2018, the last recorded national submission was made on the Alcohol Reform Bill in 2011. [14]

By 2012 a Home and Country reader was daring to ask the unthinkable: ‘Are we past our use by date?’ [15] Financially, alarm bells had already begun ringing, and were still doing so in 2018. By then WI had shrunk by 80 per cent since 1992, with 4000 members thinly distributed across 245 institutes. Once-vibrant federations such as Eastern Southland had evaporated.

Besides clinging to old forms, the greatest barrier to change had been older women’s difficulty grasping the changes in women’s lives. As professional housewives with limited finances, they were thrifty experts on making do. By contrast, younger women were time poor, extremely busy juggling jobs and families, and had different priorities, as well as different views on gender roles and on religion.

By the 2010s a new model was tentatively emerging, with meetings at times and places to suit younger women, organised and promoted through digital media. The change was most obvious in South Auckland, where Federation President Sarajane Crookes was tapping into an unmet need for social connection (‘friendship with a purpose’) and founding large, lively new institutes.

Another new champion, national gardening personality Lynda Hallinan, was using her social media platforms to promote her ‘freshly minted institute in Hunua meeting for posh nosh and a few bevvies at the local winery’. Hallinan’s grandmothers had both been Institute stalwarts; she invoked nostalgia for their era, while also poking fun at past pieties. [16]

In 2018 the colourful WI website and Facebook pages showed younger women having creative fun, celebrating events such as Suffrage 125, and, above all, promoting kindness – for example, the ‘Lonely Bouquet’ campaign to celebrate Awareness Week, where members pooled resources to create small floral posies to be left in random public places, with notes attached inviting the finder to give them a home.

Jess Paton, Districts Post

Women from the South Auckland Federation of Women’s Institutes marching to celebrate the 125th anniversary of women’s suffrage in September 2018. Note that as well as a modern banner, the women also carry a historic banner, both with the organisation’s motto ‘For Home and Country’.

Despite membership shrinkage, the Federation still punched above its weight in charitable work, giving $15,000 scholarships every two years to medical research projects and grants to Kidney Kids cumulatively totalling $110,000, plus donating goods and time, with a staggering 110,805 volunteer hours reported to the Charities Commission in 2016. Ironically, the Commission’s reporting standards not only cost WI more than $20,000 per year in professional fees, but were one of the reasons for many smaller institutes closing.

The energies being marshalled for the 2021 centennial gave members a chance to determine whether WI was a spent force, or was finally reinventing itself to continue enriching women’s lives – and their communities – in the 21st century. Certainly some younger women, while hugely enthusiastic for the social and community connections they had formed in their new local groups, made It clear that members were eyeing the national affiliation critically, measuring its value and pondering whether they might operate just as well independently.

Rosemarie Smith

Notes

[1] A goodly thing, pp. 1–2.

[2] Harper, 1960, p. 9.

[3] A goodly thing, p. 6.

[4] Rissington Scrapbook.

[5] Mabel Christmas, Tui's Annual, 10 October 1929.

[6] New Zealand Dairy Exporter, 22 January 1927.

[7] Harper, 1960, p. 10.

[8] Val Eliason, letter to National Farming News, 22 April 1991.

[9] Outline of history and annual report 1931–32, front cover.

[10] Home and Country, Sept/Oct 1995.

[11] Home and Country, Jan/Feb 2015.

[12] Mangawai Focus, 25 June 2018. Available from: http://www.mangawhaifocus.co.nz/Archives/25th+June+2018/Mangawhai+Womens+Institute+celebrates+80+years.html

[13] Raupare Women’s Institute, Submission to the Law and Order Select Committee on the Sentencing and Parole Reform Bill, 2009.

[14] New Zealand Federation of Women’s Institutes, Submission to the Justice and Electoral Committee on the Alcohol Reform Bill, 3 March 2011.

[15] Home and Country, May/June 2012.

[16] Hallinan, Lynda, ‘Meghan Markle and NZ's Women's Institute agree on one thing’, Stuff, 8 April 2018. Available from: https://www.stuff.co.nz/life-style/102811322/lynda-hallinan-meghan-markle-and-nzs-5000strong-womens-institute-agree-on-one-thing

Unpublished sources

Country Women's Institute collection, Napier Museum (includes Rissington Women's Institute minutes; annual reports 1922–1926; Rissington Scrapbook; A. E. J. Spencer diary transcripts)

New Zealand Federation of Country Women's Institutes records, 1921–2018, NZFWI Headquarters, Lower Hutt, Wellington

Holt, Margaret, former Dominion president, interviewed by Rosemarie Smith, February 1992

Published sources

A goodly thing [a history of the WI 1921–1946], Women's Institute, Wellington, 1946

Courtney, Janet E., Country Women in council, Oxford University Press, London, 1933

Harper, Barbara, The history of the Country Women's Institutes in New Zealand 1921–1958, Whitcombe & Tombs, Christchurch, 1960

Home and Country, 1927–2016

New Zealand Country Women’s Institutes, Portrait of change: a record of Country Women's Institute in New Zealand, New Zealand Country Women’s Institutes, Wellington, 1996

Outline of history and annual report, 1931–32, Women's Institute, Wellington, 1932

von Dadelszen, J.H., 'The Havelock Work, 1909–1939', Archifacts, No. 2, June 1984, pp. 39–46

Community contributions