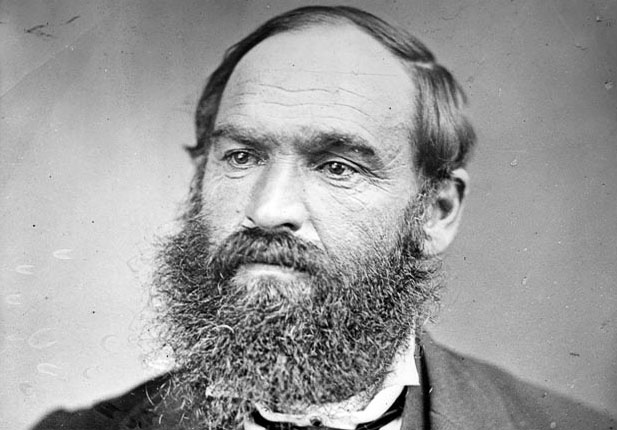

The career of John Bryce, known to many students of 19th-century New Zealand history as the Native Minister who led the invasion of Parihaka, is an interesting example of how to approach historical perspective. In the eyes of many Māori he was Tangata Kōhuru – The Murderous Man, while in his own settler community he was referred to in much kinder terms as ‘Honest John’.

On the west coast of Te-Ika-a-Māui (North Island), Ngāti Ruanui leader Riwha Tītokowaru began fighting a battle of resistance against land confiscation by the settler government in the winter of 1868. Local European settlers formed the Kai Iwi Yeomanry Cavalry Volunteers to help oppose Titokowaru and his ‘Hauhaus’ (followers of the Pai Mārire religion founded by Te Ua Haumene). This new religion, based on the principle of ‘goodness and peace’, became known as Hauhau (Te Hau – the breath of God). Pai Mārire disciples travelled across the North Island in the mid-1860s. To settlers, followers of Pai Mārire were at best troublemakers, and more likely ‘rebels’. Tītokowaru – a former Methodist lay preacher – became a Pai Mārire adherent following Te Ua’s death in 1866, and was seen by some as Te Ua’s successor. So was Te Whiti-o-Rongomai III, who at this time began to develop Parihaka as a site of passive resistance.

Rusden, G.W., History of New Zealand, Melville, Melbourne, Mullen and Slade, London, 1895

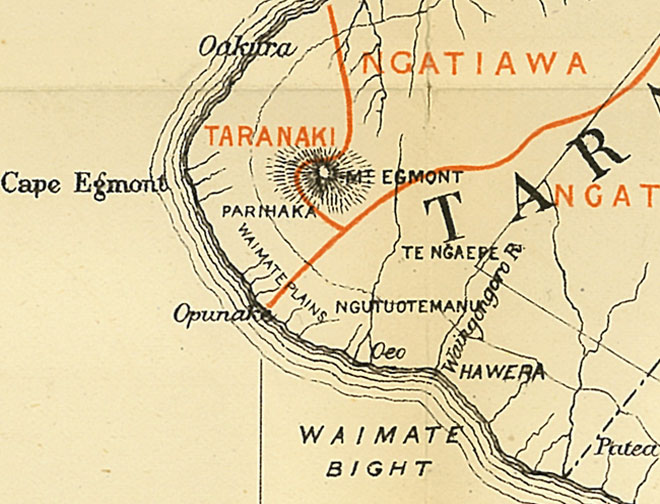

North Island map showing the government's understanding of iwi boundaries. This section of the map shows the location of the Parihaka settlement. Download a hi-res pdf (29 mbs).

John Bryce, a local farmer, was commissioned as a lieutenant in the Kai Iwi Volunteers. An official report published in a Whanganui newspaper said that on 27 November 1868, Bryce and his volunteers came upon a group of Māori at William Handley’s woolshed at Nukumaru (near Whanganui), and killed eight ‘Hauhaus’ with ‘sabre, revolver or carbine’.

In reality, the Kai Iwi Volunteers attacked a group of unarmed Māori children aged between six and 12. James Belich gives an account of this attack in ‘I shall not die’: Tītokowaru’s War New Zealand 1868–1869. He describes the brutal killing of a 10-year-old Ngā Ruahine boy, Kingi Takatua, whose head was cut in half in the attack. Another young boy, Akuhata Herewini, was also killed. According to Vincent O’Malley (2019) the other children were seriously injured. Belich maintains that the Kai Iwi cavalry admitted later they could see they were going after children ‘and charged in for the kill, not despite the fact that their quarry were unarmed children, but because of it’.

It is said that because of this incident, Bryce was known to local iwi as Tangata Kōhuru – ‘the murderous man’. Bryce would become Native Minister and many in the settler community referred to him as ‘Honest John’. He was to lead the violent invasion of Parihaka by colonial troops on 5 November 1881.

Some time between that incident in 1868 and the Parihaka invasion, a map was produced by the Defence Office in Wellington. It marked tribal boundaries, confiscation lines, and sites such as ‘Gate Pah’ (where there had been a battle on 29 April 1864), ‘Te Kooti’s Landing Place’ at Whareongaonga (July 1868) and Parihaka itself (established in 1866).

Two years after the invasion of Parihaka, G.W. Rusden published a three-volume History of New Zealand in which he outlined the brutal attack at Handley’s woolshed. He reported that Bryce and Sergeant G. Maxwell had dashed upon women and children and ‘cut them down gleefully and with ease’ (Rusden, History of New Zealand, vol. 2, 1883, pp. 504–5). Rusden’s account of this event prompted debate in New Zealand’s House of Representatives, with one member giving notice of a ‘resolution that the government should pay the expenses of prosecuting the author’ (Rusden) for bringing the New Zealand government into disrepute. According to the New Zealand Parliamentary Debates of 1883 the resolution was not carried. Instead, Bryce took a civil case, suing Rusden for libel in the High Court in London. Bryce won his case on the basis that he personally had not carried out the killings and that no women were involved, as Rusden had claimed.

While Bryce was never charged over the matter, as an officer in the Kai Iwi Yeomanry Cavalry Volunteers he bore some moral responsibility for the events of that day. Irrespective of the legal arguments, a unit in which Bryce was a commissioned officer had murdered innocent children, and Bryce and his superior had covered this up. Māori knew about this widely enough to dub him the ‘murderous man’, or the Murderer Bryce (Kōhuru Bryce).

Rusden’s history has been largely lost to Pākehā memory. Papers Past is a rich repository of the media record of the time. It is worth looking at how the ‘attack’ at Handley’s woolshed was described in the Wanganui Herald. This account bears little relationship to the truth which was revealed during Rusden’s trial.

I wonder if the incident is not discussed more in historical circles because Māori (oral) memory is, in the eye of the courts and the academic world, usually considered inferior to Pākehā written histories. Dr Nepia Mahuika explores this idea in much of his work. Māori knew Bryce was a murderer in spirit as a leader of the volunteers who had killed those children. Parihaka proved him to be a brutal man indeed – but the settler government managed to largely suppress that story too. In The Parihaka album: Lest we forget (2009), historian Rachel Buchanan points out how in Taranaki and other iwi oral traditions, many children are still named to keep alive the memory of what happened to their tupuna – Toto (blood) and Mamae (hurt) as well as Mōrehu (survivor) are names given to children to remember their history. Other ways of remembering and sharing knowledge are through kōrero on the paepae and with the whānau, through whakairo and ngā mahi o te whare pora – as Lillian Hetet Owen puts it, ‘In the absence of a written literature, carving and weaving is our visual literature.’

Rusden, G.W., History of New Zealand, Melville, Melbourne, Mullen and Slade, London, 1895

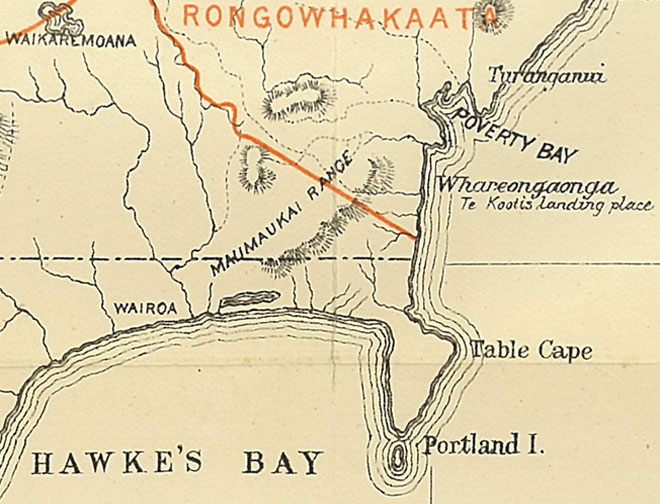

North Island map showing the government's understanding of iwi boundaries. This map was based on a copy produced by the government Defence Office in the late 1860s. Download a hi-res pdf (29 mbs).

I stumbled upon this map when I looked at physical copies of the 1895 second edition of G.W. Rusden’s History of New Zealand, revised after he was found guilty of libelling Bryce. It has not previously been available in digital form; although the main text had been digitised, the map had not. This just goes to show that going back to original sources is sometimes worthwhile! The map is reproduced here as a classroom resource, since most teachers and students don’t have the privilege of working just along the road from the National Library, where these books are held. It can be printed A3 or larger and is a useful tool for discussing the New Zealand Wars, and some of the battles which occurred between Northland and Wellington over three decades.

The Defence Office felt they were facing major internal threats. This map was created in the wake of two significant conflicts in the North Island: Tītokowaru’s campaign against confiscations on the west coast and the violent pursuit of Te Kooti on the east coast. In 1868 Te Kooti had escaped from the Chatham Islands (can you find the area marked ‘Te Kooti’s landing place’?) where he had been exiled without trial since 1866. For nearly four years he waged a guerrilla war unlike any previous conflict in the New Zealand Wars. Māori and colonial troops pursued him across the central North Island and Te Urewera until he was granted sanctuary by the Māori King, Tāwhiao, in 1872.

Emma Jean Kelly, Educator

Discussion / teaching points

The map offers a way into a wider or a more specific conversation about the New Zealand Wars in which connections could be made, different viewpoints considered, evidence assessed, and explanations and interpretations built. Kaiako could discuss the following questions:

Why do you think the Defence Office produced a map like this at this time?

Find the black straight lines in various areas on the map. These are confiscation lines. Whose land was being confiscated? Why was the government confiscating land?

Investigate the way that iwi Māori viewed landscape and how they defined iwi boundaries. How would Māori have represented boundaries at this time?

Te Puni Kōkiri have created this map of iwi boundaries today. Look at this map and compare it with the Defence Office map. Are there noticable differences?

A version of this map is held at the Alexander Turnbull Library. It is a primary source document, one of many held in our national institutions. It records the Defence Office’s perspective on what was happening in 1860s New Zealand. The Wanganui Herald also presents a secondary source of ‘evidence’ regarding what happened at Handley’s woolshed.

Where is the iwi perspective recorded?

How do students work out which evidence to believe?

In considering historical perspective, consider why it is possible for people to see John Bryce in such contrasting terms – as ‘Tangata Kōhuru’ or as ‘Honest John’?

Further information

Waitangi Tribunal, Taranaki report, 1996 (.pdf)

Belich, James. ‘I shall not die: Titokowaru’s War New Zealand 1868–1869, Allen & Unwin, Port Nicholson Press, Wellington, 1989

Buchanan, Rachel. The Parihaka Album: Lest We Forget, Huia, Wellington, 2009

Owen, Lillian Hetet, in Hanahiva Rose, ‘Whānau Hetet’, Capital Tales of the City, no. 62, Winter 2019, p. 48

O’Malley, Vincent. Ngā Pakanga o Aotearoa / The New Zealand Wars, Bridget Williams Books, Wellington, 2019

Rusden, G.W. Preface to the Second Edition, History of New Zealand, Melville, Melbourne, Mullen and Slade, London, 1895

Community contributions