The two names of this hill – Pukeahu and Mount Cook – reflect its rich history. Māori have had a long association with Pukeahu, from pre-contact times until the present day. European settlers, recognising its prominent position, began using and changing the hill as early as 1840.

What does Pukeahu mean?

Pukeahu is an old name and there is no record of why the hill became called this. In te reo Māori, ‘puke’ means hill, and ‘ahu’ is to heap up, so the meaning is ‘raised hill’. ‘Ahu’ may derive from the kupu ‘tūāhu’, which can refer to an altar or stone platform, or the central stone of a marae. So Pukeahu (sometimes spelt ‘Puke Ahu’) may suggest the idea of a ‘sacred hill’ – a place to perform rituals.

Honiana Love (Te Āti Awa) suggests Pukeahu had connections with two other significant peaks, Puke Ariki (in Belmont) and Pukeatua (above Waiwhetū). Since European settlement began in earnest in the 1840s, Pukeahu has been heavily modified, leaving little of the pre-colonial landscape intact. Over the years, construction projects flattened off the cone-shaped hilltop lowered it by around 30 metres, so any remnants of Māori use, and occupation are likely to have long since disappeared.

Honiana Love, Taunaha Whenua Naming the Land – Ngā Taonga Sound & Vision

George Leslie Adkin, The great harbour of Tara (1959) – Wellington City Recollect

New Zealand Electronic Text Centre

Detail of a 1916 map of Wellington showing Māori place names compiled from information supplied by ethnographer Elsdon Best.

Why Mount Cook?

European settlers renamed Pukeahu as Mount Cook, after the British explorer Lieutenant James Cook, whose ship Endeavour first sailed around New Zealand in 1769–70.

Between the ridges

Pukeahu sits between two dominant ridgelines. The first, Te Ranga a Hiwi, extends from Point Jerningham (Orua-kai-kuru) up to Matairangi (Mount Victoria), then runs south to Haewai (Houghton Bay) and Uruhau, above Island Bay. The other ridgeline runs from Te Ahumairangi (Tinakori Hill) to Te Kopahou (Red Rocks) on the south coast. This ridge connects with Te Rimurapa (Sinclair Head) in the west and the Tawatawa Ridge, which separates Island Bay from Ōwhiro Bay.

Beside the flats

The name Huriwhenua represented the flat area of Te Aro, between Pukeahu and Wellington Harbour. The Waitangi Stream flowed through the valley to the east of Pukeahu, with the Waimāpihi Stream to the west. The low-lying Basin Reserve area was a repo (swamp) known as Hauwai.

Vegetation

Forests of pukatea, tōtara, northern rātā, rimu, kohekohe, tawa, hīnau and mānuka once covered the area between the harbour and the south coast. Various paths ran through this area, and from the earliest settlements Māori cleared land for gardens.

New Zealand Company draughtsman Charles Heaphy, recalling his first visit to Port Nicholson (as Wellington was then known by Europeans) in 1839, before the arrival of European settlers, said Tinakori Hill was ‘densely timbered … the rata … being conspicuous’. Wellington Terrace (where The Terrace is now) was ‘timbered chiefly with high manuka’, around 12 metres high. High fern and tutu covered Te Aro, while Hauwai was a ‘deep morass’. [1]

A changing landscape

The 1848 Marlborough and 1855 Wairarapa earthquakes both changed the landscape of the area. The earthquakes raised land around the harbour and the authorities used prison labour to drain Hauwai and then transform it into a cricket ground that is known today as the Basin Reserve.

First settlement and iwi migrations

Alexander Turnbull Library, A-049-001

Ngāti Mutanga first established Te Aro pā in 1824. Other iwi occupied it in later years. This drawing is from around 1842.

Te Kāhui Maunga

The first tangata whenua of this area are said to have been Te Kāhui Maunga, who have also been called Kāhui Tipua and Maruiwi.

Ngāi Tara

Ngāi Tara was the first iwi to settle in this area. Possibly as early as the late 13th century, its Ngāti Hinewai hapū (subtribe) established the major pā (fortified village) of Te Akatarewa on the slopes of the hill Europeans named Mount Alfred, above where Wellington College and Wellington East Girls’ College are today.

Ngāti Rangi and Ngāti Ira

Ngāti Rangi displaced Ngāi Tara over time. They were in turn displaced by Ngāti Ira – the descendants of Ira-kai-pūtahi – who lived on the Huriwhenua flat and in other places around Te Whanganui-a-Tara (the great harbour of Tara, or Wellington Harbour).

Taranaki iwi

Ngāti Ira were displaced from Te Whanganui-a-Tara by iwi from Taranaki – firstly Ngāti Mutunga and Ngāti Tama, and then Te Ātiawa and other Taranaki peoples. These migrations were prompted by Ngāti Whātua and Ngāpuhi war parties making forays into Taranaki from the north between 1818 and 1821 – a period of conflict popularly known as the Musket Wars. Te Akatarewa pā and the area around Pukeahu may have been unoccupied when Taranaki iwi arrived.

Te Aro pā

Te Aro pā was on what was then the waterfront, in the area where Manners Street and Taranaki Street now meet. Ngāti Mutunga established the pā in 1824 and occupied it until they left to settle in the Chatham Islands in 1835. Ngāti Tupaia and Ngāti Haumia, along with their Te Āti Awa kin were the next occupants.

People moved between pā and Te Āti Awa occupied much of the Wellington area, with coastal settlements at Paekawakawa (Island Bay), Ōwhiro, and Waiariki and Ōterongo, both on the coast between Sinclair Head and Cape Terawhiti. Te Āti Awa also had settlements around the harbour at Kumutoto (present-day Woodward Street), Pipitea (Thorndon Quay), Kaiwharawhara, Ngauranga, Pito-one (Petone), Hikoikoi/Waiwhetū and on the coast towards Pencarrow Head.

Alexander Turnbull Library, E-455-f-034-1

This 1852 painting shows two Māori figures standing on the road to the Mount Cook barracks. The flax bushes at the side of the road show what the vegetation in the area was like before Europeans arrived.

Cultivations

Ngakinga (gardens) for the nearby Te Akatarewa pā covered the land around Pukeahu. This was a major pā for Ngāi Tara, so they developed garden sites to feed its occupants. Taranaki iwi from Te Aro pā used these same gardens centuries later.

The earliest gardens cultivated aruhe (bracken fern) for its edible roots. This simply involved clearing the forest and allowing the regrowth of ferns. Māori later terraced the hills to grow kūmara (sweet potato). They planted potatoes, melons, and corn following contact with Europeans. These garden clearings extended into Aro Valley and Newtown and were in active use when the New Zealand Company’s surveyors arrived in 1839.

The Hauwai cultivation area bordered the Hauwai swamp and ran up the hill to around where the entrance to Wellington College is today. Hauwai swamp was a mahinga kai (food-gathering area) for tuna (eels) and other fish from the swamp’s streams.

Ngā Kumikumi clearing was an old cultivation area in the bush around what is now lower Nairn Street. Nearby, around Central Park and Maarama Crescent, was a Te Āti Awa kāinga (village) known as Moe-i-te-rā or Moe-rā.

The arrival of Europeans

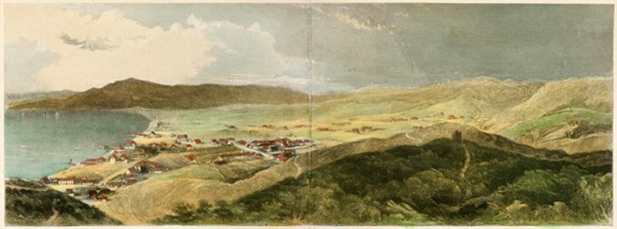

Alexander Turnbull Library, C-025-009

Charles Heaphy painted this picture of Wellington in 1841 for the New Zealand Company. Pukeahu Mount Cook is in the middle of the picture, with a dirt road winding towards it.

Early European visitors

From the early 19th century, the European whalers and sealers working in New Zealand waters established shore stations around Te Moana-o-Raukawa (Cook Strait), and on Mana and Kāpiti islands. The first European vessel known to have entered Te Whanganui-a-Tara was the sealing brig Wellington under Captain John Day in mid-1823. This was a ‘curious coincidence’, given the name of the city that later grew around the harbour. Captain Barnett if the ship Lambton charted the harbour in 1826 and presented it to the Sydney harbour master Captain John Nicholson, after whom Barnett had named the port.

By the 1830s whaling ships operated in Te Moana-o-Raukawa. There are reports of Europeans living with local iwi, operating as traders, before formal settlement began in late 1839.

Port Nicholson (Wellington Harbour) – Te Ara The Encyclopedia of New Zealand

The New Zealand Company

In August 1839, the sailing ship Tory arrived in Te Moana-o-Raukawa carrying representatives of the New Zealand Company, which intended to purchase land and prepare settlements for the British emigrants the company was recruiting.

Te Āti Awa chiefs Te Puni and Wharepōuri signed a deed of purchase with the New Zealand Company in September 1839, although there were later concerns about the validity of this transaction. The deed promised that Māori would retain their pā, kāinga, cultivations and mahinga kai. Furthermore, ‘A portion of the land ceded by them, equal to one-tenth part of the whole, will be reserved by … the New Zealand Company … and held in trust by them for the future benefit of the said chiefs, their families, and their heirs for ever.’ [2] These ‘native reserves’ included ‘Cooks Mount’ (Pukeahu) and two neighbouring acres.

The New Zealand Company’s first settler ship, the Aurora, arrived at Pito-one (Petone) on 22 January 1840, and a community was set up there. However, after this settlement flooded in early March, the settlers moved across the harbour to Thorndon and Te Aro. By the end of the year, 1,200 British settlers had arrived in Wellington, outnumbering the Māori in the area.

The New Zealand Company parcelled up the land into sections for settlers, each of whom was to get one town acre (0.4 hectares) and an accompanying 100 country acres (40 hectares). There were 1100 one-acre town sections in the plan for Port Nicholson. The New Zealand Company surveyors took little account of the sites promised to Māori and, as the city grew, Māori moved away.

From Pukeahu to Mount Cook

Alexander Turnbull Library, A-292-071

An 1849 sketch of Wellington, done from near where the Beehive is today. Mount Cook is in the distance, with the military barracks on its levelled but still prominent peak.

The arrival of European settlers saw Pukeahu renamed Mount Cook, after the British explorer James Cook. In the period since, a range of functions have shaped the hill’s form and identity.

The impact of European settlement

New Zealand Company surveyor Captain William Mein Smith recognised the strategic advantage of the hill. By late 1840 a prison was situated on Mount Cook, even though the land was still a native reserve. In 1842 there were reports of 60 prisoners held there, although the building was ‘a wretched maori building, large enough for twelve or fifteen human beings at the most.’ [3]

As well as serving as a site for a succession of prisons and a police station, the military used Mount Cook in the 19th century. It was the site of a brickworks and educational institutions. Lesser-known uses included being the site of an official observatory for the 1882 transit of Venus and Wellington City Council’s dog pound. Today, Pukeahu/Mount Cook is most associated with the Dominion Museum building, a high school, a university, and the National War Memorial.

Law and order and the military

Alexander Turnbull Library, PA1-f-019-17-3

View of Te Aro in 1858. It shows the upper Mount Cook barracks on the hill in the background at right, and the lower Mount Cook barracks and Buckle Street at the foot of the hill.

There has been continuous military presence at Mount Cook for over 180 years, and military and policing functions have often gone hand in hand.

First military presence on Mount Cook

As early as 1841, Governor William Hobson approved plans for military barracks on the summit and a gaol on the southern boundary of Mount Cook. The first unit stationed at Mt Cook – 55 men of the 96th Regiment – did not arrive until July 1843, following the Wairau incident near present-day Blenheim. They camped in tents at the base of the hill, surrounded by light palisades in case of Māori attack.

Before the arrival of the 96th Regiment, work had already begun on a two-storeyed brick gaol on the hilltop, which was to be ‘made as strong as bricks and mortar can make it.’ Prisoners from the Pipitea Street penitentiary levelled the ground and prepared the foundations. However, there were people who believed that this would be the best site for a barracks, and even before completion of the gaol there were calls to remove the ‘eye sore’.

The military base expands

In 1846, fighting between Māori and the Crown in the Hutt Valley and Pāuatahanui saw more troops stationed at Mt Cook. Space was now at a premium. Authorities erected two wooden barracks and a powder magazine in 1847, with the expectation of a permanent garrison of the 65th Regiment and attached Royal Engineers and Royal Artillery units.

The military base then expanded. Engineers lowered the hill by around 14 metres, and two acres of land earlier reserved for Māori confiscated. The addition of barracks and other buildings on the harbour side of Buckle Street at the foot of Mount Cook led to a distinction between ‘Upper’ and ‘Lower’ Mount Cook.

The 1848 Wellington earthquake interrupted this expansion and forced the closure of the prison. Wooden buildings, which suffered less damage in earthquakes, replaced the brick ones. Military ordnance stores in Manners Street were also severely damaged so, in 1850, the Board of Ordnance assumed control of 13 acres of land at Mount Cook, starting its long association with the area.

Mount Cook was now Wellington’s main fortification. However, an 1852 report by the Royal Engineers stated that, because of its location on the outskirts of the built-up area, ‘It … affords no protection to the Town which is entirely without defences.’

Constabulary at Mount Cook

In 1859 the 14th Regiment of Foot relieved the 65th Regiment. They were then replaced by the Militia and Volunteers Office in 1865 as British regiments withdrew from New Zealand. Two years later, authorities formed a permanent colonial fighting force, the Armed Constabulary (a forerunner of both the New Zealand Army and the New Zealand Police). It was based at Lower Mount Cook.

Before the transformation of Hauwai swamp into the Basin Reserve in the late 1860s, Lower Mount Cook was a venue for public cricket matches. The military built further structures, including drill halls, a gymnasium, and an artillery depot, on the site during the 1870s and 1880s.

In the 1870s, the barracks at Upper Mount Cook became temporary quarters for immigrants who arrived under a government scheme. Reports stated that the barracks were ‘better or more comfortable quarters in any way are seldom, if ever, provided for the accommodation of immigrants.’ [4] In the late 1870s they were a temporary prison, most notably for the men arrested at Parihaka after passively resisting the confiscation of their land by the government.

The expansion of the New Zealand Constabulary Force (the renamed Armed Constabulary) in the 1880s, saw more buildings added, along with coast defence guns for training purposes. In 1892 there was a typhoid outbreak due to the insanitary state of the wooden buildings, prompting the abandonment and quarantining of the complex for 15 months.

Police station

Te Aro was the fastest growing suburb in Wellington in the 1880s, with a crime rate to match. Newtown had acquired a police station with a sole-charge constable in 1878, but there was a need for increased policing in the area. The Mount Cook police station was one of three opened in Wellington in 1894. Like other buildings in the area, the police station was built from bricks made by prison labour.

New prison

Alexander Turnbull Library, EP-3276-1/2-G

This photograph shows the derelict Alexandra Barracks in 1929. The original purpose of the building was as a prison.

In 1883 planning started for a new prison on the summit of Mount Cook. The prison would replace the immigration hostel, which had closed following the ending of assisted immigration in 1881. Construction saw the hilltop lowered by another ten metres. The design was based on Pentonville Prison in London, which enabled round-the-clock observation of inmates. The building used bricks made on site by prisoners marched across Te Aro each day from the Terrace Gaol.

When construction work stopped in 1900, builders had only completed one wing and the basements of two other wings. Local opposition to its forbidding design and prominent location saw prison plans shelved. Authorities considered other options for the building, including a museum, an asylum, and a relocated Victoria University College (later Victoria University of Wellington Te Herenga Waka).

The military takes over

In the end the military took over the prison, using it for stores and barracks. Further excavation works brought the underground basements up to ground level. Renamed Alexandra Military Depot in 1903, it became popularly known as Alexandra Barracks. The front offices of the barracks housed the General Headquarters of the Permanent Artillery (New Zealand’s small standing army) and the Council of Defence for a period.

By 1907 older buildings in Lower Mount Cook needed replacement. Work started on new brick buildings, including the Defence Stores Office (later called the General Headquarters Building), which still stands on the corner of Buckle and Taranaki streets.

The Mount Cook complex served as a base for the mounted special constables who were popularly known as ‘Massey’s Cossacks’ during the 1913 waterfront strike. Violent clashes between strikers and special constables occurred around the Defence Stores Office. Machine guns were on open display in Buckle Street to intimidate the local working-class population.

The 1913 Great Strike – NZHistory

The First World War

During the First World War, the existing Mt Cook store facilities proved inadequate in equipping the overseas New Zealand Expeditionary Force, which numbered 24,000 by the end of the war. In late 1914 the army opened temporary stores at their Trentham (Upper Hutt) training camp. The stores moved permanently to Trentham in 1930, allowing General Headquarters to move into the stores building.

Between 1917 and 1919, Alexandra Barracks held conscientious objectors. Future Labour Party leader Harry Holland, who was then editor of the socialist newspaper Maoriland Worker, reported that ‘Fourteen lads … had been flung into prison here … [T]he three Baxter brothers were each sentenced to 28 days in Alexandra Barracks, then to 84 days in the common jail, and again to 28 days in Alexandra Barracks.’ [5]

Gallery, museum, and war memorial

In 1931 authorities demolished the unoccupied and now derelict Alexandra Barracks to make way for the National Art Gallery and Dominion Museum building, and the National War Memorial Carillon. The carillon was dedicated on Anzac Day (25 April) 1932, and the Hall of Memories below it finally completed in 1964.

The National Art Gallery and Dominion Museum opened in 1936 in an imposing neo-classical building. The institution closed in 1996, reopening in 1998 on reclaimed land on the Wellington waterfront as the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa.

The Second World War and after

During the Second World War, expanding military needs put further pressure on Lower Mount Cook. The military enlarged existing buildings in June 1942 the War Cabinet took over the art gallery and museum building, basing the Royal New Zealand Air Force there from late 1943 until mid-1946. Air-raid shelters, both tunnels and trenches, were dug into the hill, and underground bunkers built behind the museum.

A new building constructed behind the General Headquarters building in 1941–42 served as the headquarters of the army’s Defence Transport Services. The Defence Services Transport Pool used this building, known as the Home Command Building by the late 1970s, until 1986. It was the home of the Wellington division of the Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve from 1978 to 2015. The Wellington division was known as HMNZS Olphert after its first commander, Captain Wybrants Olphert. This earthquake-prone building was demolished in 2019.

Brick-making

Alexander Turnbull Library, 1/4-015511-F

Enoch Tonks’s brick factory on Webb Street, near Pukeahu. This photograph shows what a typical brick factory looked like in the 1890s.

From the 1860s until the 1950s Mount Cook boasted major brick-making sites, both at the prison and on surrounding streets, including Wallace Street (Hill Bros), Taranaki Street (Murphy Bros), Webb Street (Tonks) and Hanson/Tasman Street (Back/Overend). The hilltop provided a plentiful supply of clay for prison bricks. The Murphy Bros works continued to operate on Taranaki Street until 1952, on the site that is now Wellington High School’s playing field.

Prison bricks

Alexander Turnbull Library, 1/2-104075-F

Alexandra Barracks and Mount Cook Prison brick factory with its tall chimney in the centre of this 1899 photograph of Wellington city.

As the Mount Cook prison did not house any prisoners, Terrace Gaol (on the site of Te Aro School) prisoners, marched to Mt Cook in irons each day, made the bricks.

The prison bricks, marked with an arrow to indicate that they were government property, were of ‘superb quality’ and ‘without equal’. [6] Used in buildings on Buckle Street, including the 1894 police station, the 1907 Garrison Hall and the 1911 Defence Stores, other buildings in the city used the bricks with the arrow markings concealed, including the interiors of Parliament House. The arrows are visible on the bricks used in the retaining wall on Tasman Street, built around 1900.

Closure of the brickworks

While other private brickworks in the area closed or moved, the Mount Cook prison brickyard remained in operation until 1920. Before leaving the site, the prisoners had one last task – to demolish the brick kiln, gaolers’ quarters, and workshop in preparation for the construction of Wellington Technical College.

Education

First schools on Mount Cook

In the early 1870s, small public schools or private tuition were the only educational opportunities for school-aged children in Wellington. Then in 1875, separate girls’ and boys’ schools started in a building on the northern side of Buckle Street, at its intersection with Tory Street. Two years later, Mount Cook Infants’ School for three- to eight-year-olds opened on the opposite side of Tory Street. This was New Zealand’s first kindergarten school.

Rapidly increasing rolls at both the boys’ and girls’ schools soon put pressure on the space. In 1878, Taranaki Street Boys’ School opened on a site opposite Webb Street. Buckle Street Girls’ School remained at the Buckle Street site. In 1906, all three schools came under the leadership of one principal. From the late 1880s until the 1920s there were ongoing issues with overcrowding and, later, with the standard of the buildings.

In 1925 construction started on a new building to accommodate all three schools. A year later, Mount Cook Main School opened on Buckle Street. In the mid-1970s Mount Cook School moved again, to a wooden building a short distance down Tory Street from its intersection with Buckle Street. The old brick building on Buckle Street was demolished.

Wellington City Council had long felt that Mount Cook was more suited to an educational role than a penal or military one. In 1895 the council asked the government to set aside the Mount Cook reserve for a university or other educational institution, instead of a prison or asylum. Despite overcrowding at Mount View Lunatic Asylum (on the site of today’s Government House), Inspector of Asylums Dr Duncan MacGregor rejected the option of moving the institution to Mount Cook.

The idea of using Mount Cook for educational purposes emerged again in 1898, when Victoria University College, founded the previous year, was looking for a permanent site for their campus. In the event, the college was based briefly in Thorndon before moving to its present location in Kelburn.

Wellington Technical College

Wellington College of Design was founded in 1886, and by 1905 it was starting to outgrow its premises on the corner of Mercer and Wakefield streets. Now renamed Wellington Technical College, it was increasingly popular with primary school leavers after it became the first New Zealand school to provide a general secondary education with a technical bias. College director William La Trobe proposed Mount Cook as a location for a new campus.

The government initially rejected this use for Mount Cook, even though they no longer required the site for penal purposes. Wellington City Council favoured the John Street site where Te Whaea (the New Zealand National Dance and Drama Centre) is now located. La Trobe persevered with his advocacy of Mount Cook, envisaging a vast multi-purpose campus: ‘There is ample room for technological laboratories, museum, art galleries, storehouses for the archives of the country, on the same site.’ [7]

In February 1918, an ‘influential deputation’ representing education, business and industry bodies lobbied the government to ‘place at the disposal of the educational authorities ... about four acres of land at the southern end of the Mount Cook reserve … [S]ufficient grants in money [should] be provided to enable the college, without long delay, to be established on that site.’ [8]

Alexander Turnbull Library, 1/1-023103-G

The main Wellington Technical College building is in the centre of this photograph taken in 1934 during the construction of the National Art Gallery and Dominion Museum building in front of the college.

Work started in 1920, with prisoners from the Terrace Gaol used to clear the brick kilns, level the ground, and remove a gaolers’ quarters and workshop. Governor-General Lord Jellicoe laid a foundation stone in March 1921. In May 1922, the first students moved in, while building work continued around them. Building finished on the main two-storey block in 1924, when the new school officially opened. Over the next 10 years, the college relocated in stages to the new facilities following the addition of other buildings and wings.

Wellington Polytechnic and Wellington Technical High School

By 1960 there were 1,100 students at the day school and 5,000 adult students taking technical courses in the evening. The Education Department decided to divide the secondary and tertiary strands into separate institutions – Wellington Technical High School (later Wellington High School) and Wellington Polytechnic, respectively. The high school would retain the existing buildings, while the polytechnic would move south into new facilities on adjacent land on Wallace Street.

During the construction of the new campus, the polytechnic shared rooms in the high school and added prefabricated buildings. It began occupying the new buildings in 1970, and completely vacated the high school building two years later. The polytechnic continued to develop and expand on its new site.

From polytechnic to university

From 1992, the polytechnic’s School of Design and Victoria University of Wellington conjointly delivered New Zealand’s first university design degree course. In 1997, Wellington Polytechnic and Massey University agreed to a merger. They completed the merger in 1999, the same year Massey added the former National Art Gallery and Dominion Museum building to its Wellington campus.

Wellington High School rebuilds

The expansion of Wellington High School started in 1967, with land on Taranaki Street purchased and plans for a new school drawn up. It was not until 1977 that the rebuilding began, with the main classroom and administration block completed and occupied in 1980. Completion of the remaining blocks occurred in 1983. The school made the decision to demolish the original brick block during the 1984–85 summer holidays but retain the hall and an adjacent cafeteria. The cafeteria reopened in 1985 as PolyHigh early childhood education centre, and the hall refurbished in 1995.

Pukeahu National War Memorial Park

Created in 2015, Pukeahu National War Memorial Park is the national place for New Zealanders to remember and reflect on this country’s experience of war, military conflict, and peacekeeping. The park commemorates New Zealanders who have died during or served in wars or conflicts. The park is rich in local history and includes the following memorials:

- National War Memorial

- Carillon Tower

- Hall of Memories

- Tomb of the Unknown Warrior

- Ngā Tapuwae o te Kāhui Maunga The Footsteps of the Ancestors

- Australian Memorial

- Turkish Memorial

- United Kingdom Memorial

- French Memorial

- Belgian Memorial

- Pacific Islands Memorial

- United States Memorial

- 1918 Influenza Pandemic Memorial Plaque

Further information

Visiting Pukeahu – Te Akomanga

Pukeahu Park guide – Manatū Taonga Ministry for Culture & Heritage

Pukeahu: An exploratory anthology – Massey University & Alexander Turnbull Library

Notes

[1] Major Charles Heaphy, 'Notes on Port Nicholson and the Natives in 1839' in Transactions and Proceedings of the New Zealand Institute. Vol. XII, 1879 https://www.wcl.govt.nz/heritage/heaphy.html (last accessed 8 August 2024)

[2] Wellington Tenths Trust, 'Our history' https://wtt.maori.nz/about-us/history/ (last accessed 8 August 2024)

[3] New Zealand Gazette and Wellington Spectator, 9 March 1842, p. 2 https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/NZGWS18420309.2.6 (last accessed 8 August 2024)

[4] 'Upper Mount Cook Barracks', Wellington Independent, 12 March 1872 p. 128 https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/WI18720312.2.10 (last accessed 8 August 2024)

[5] 'N.Z. Conscientious Objectors' Maoriland Worker, 20 February 1918 p. 4 https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/MW19180220.2.18 (last accessed 8 August 2024)

[6] Peter Cooke Mt Cook, Wellington – A History, 2006 (PDF, 124KB)

[7] 'More room needed' Evening Post, 2 May 1917 p. 2 https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/EP19170502.2.14 (last accessed 8 August 2024)

[8] 'Too long a Cinderella' Evening Post, 13 February 1918 p. 6 https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/newspapers/EP19180213.2.33 (last accessed 8 August 2024)

Community contributions