Using this page

This page will help teachers and students to think about the concept of history through a ‘What is history?’ diagram and the use of metaphors to describe history. Hopefully the diagram and the metaphors can ignite interest, discussion and understanding about what history is. What other diagrams, metaphors and images could you use in class?

Curriculum

Linked to the process of metacognition, which encourages learners to ask reflective questions about the nature of knowledge, this page relates to the ‘thinking’ competency in the New Zealand Curriculum.

Asking questions about the nature of knowledge connects with the purpose statement outlined in Te ao tangata | social sciences learning area of Te Mātaiaho | the refreshed NZ curriculum, which encourages students to ‘observe, to wonder and be curious about people, places, and society, and to take an interest and engage in social issues and ideas.’

- Te Mātaiaho | the refreshed NZ curriculum – Ministry of Education

- Te ao tangata | social sciences – Ministry of Education

Examples outside of history

Teachers can use other diagrams, metaphors and images to describe the acquisition and creation of knowledge. The poutama pattern, the harakeke plant, and woven whāriki and kete are great examples. Having these metaphors visible in the classroom will allow students to draw inspiration from them.

What is history?

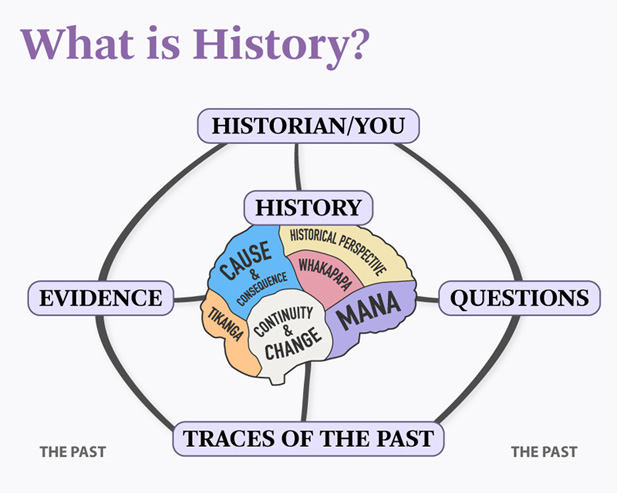

The description of history as ‘an argument without end’ is not that helpful in describing to students the process of making history. I find the diagram below useful when talking with students about what is involved when ‘doing history’. It serves as a springboard to discussion and further understanding.

Wānanga | Discussion

- Before showing them the diagram, get students to brainstorm what they think history is.

- Create a T-Chart (two-column table) on what is history and what is not history.

- Show the ‘What is history’ diagram and compare it with their ideas.

- Interrogate the diagram as you explore each step. Students can modify questions after considering evidence and narratives shift in response to further evidence.

- It is a basic diagram you can change and challenge. Adapt it for your class. With younger students, I talk about history rather than ‘historical narratives and interpretations.’ You may choose not to include the brain.

History is not the past

The diagram effectively shows that history and the past are not the same. This is a key point for students to understand. Historians create history in the present to understand and explain the past. As much as we might dream of travelling through time, the past itself is unobtainable. So, what is the process through which the past becomes history?

The historian

Putting the historian/you (i.e., the student) first invites discussion. How important is the question of authorship? British historian Raphael Samuel hoped to de-centre the role of the historian when he wrote: 'History is not the prerogative of the historian, nor … a historian’s invention. It is, rather, a social form of knowledge; the work, in any given instance, of a thousand different hands.' [1]

Kaitiaki o te pō

At a history teachers conference, Justice Joe Williams (Ngati Pūkenga, Waitaha and Tapuika) described the historian as kaitiaki o te pō – guardian of the night, charged with a responsibility to care for and look after stories from the past.

History is usually not a process of teasing out authors’ intentions or situating texts in a social world, but rather one of gathering evidence, with texts merely serving as the bearers of information. But if we remember that these texts are human creations, what people say becomes inseparable from the person who says it. It is worth remembering a maxim of E. H. Carr, who in 1961 said: ‘Study the historian before you begin to study their facts....When you read a work of history always listen out for the buzzing. If you can detect none, either you are tone deaf or your historian is a dull dog. The facts are really not at all like fish on the fishmonger’s slab. They are like fish swimming about in a vast and sometimes inaccessible ocean; and what the historian catches will depend, partly on chance, but mainly on what part of the ocean [they] choose to fish in and what tackle [they] choose to use – these two factors being, of course, determined by the kind of fish [they] want to catch. By and large, the historian will get the kind of facts [they] want. History means interpretation.’ [2] There is no history without the historian, and we must consider their interests and intentions.

Evaluating information with LEGIT – Te Akomanga

Questions

The diagram suggests that questions drive and direct the historian as they seek to come to an understanding of the past, which although inherently unobtainable, they can see through traces of the past, namely evidence.

Communicating information: writing focus questions – Te Akomanga

Evidence

Historical narratives are the product of an ongoing process of selecting and reconstructing traces of the past (research). What traces can we find – what evidence is available? Whenever we find evidence, we encounter issues around memory and bias. Evaluation and comparison of evidence is important. Certain sources of evidence are more dependable, and/or more useful, than other evidence. Sometimes there is little or no evidence; sometimes it is overwhelming. Why?

Evaluating information with LEGIT – Te Akomanga

Historical narratives and relationships

The diagram of the brain signifies the different relationships that happen when we research and create historical narratives and interpretations. Māori historians identify whakapapa, mana and tikanga as important whenu/strands. Western concepts include cause and effect, significance, change and continuity, past and present, and empathy.

Historical concepts – Te Akomanga

Te Pouhere Kōrero is a valuable resource that includes iwi approaches to the teaching of the past, citizenship education, and Te Tiriti o Waitangi.

Te Pouhere Kōrero 10 – Te Pouhere Kōrero

Te Takanga o te wā is a framework designed to support teachers teaching Māori history.

Te Takanga o te Wā Māori History Guidelines Year 1−8 – Ministry of Education

Georgia Palmer’s thesis critiques Te Takanga o te wā and outlines key concepts in Māori and iwi histories.

While the diagram concludes with ‘History’, it can be good to talk with students about the different histories that exist. Bain Attwood, for instance, writes about three ‘lives’ (or types) of history:

- the public life of history (Attwood credits Dipesh Chakrabarty with this term, which refers to the debates and discussions about history that occur in the public domain)

- the cloistered life of history (the history that occurs in the universities)

- the private life of history (the way history works as an emotional force, and the role that subjective factors play in the practices of historical research and writing).

Head, hand, and heart

The diagram of the brain illustrates historical relationships, but what about the hand and the heart? Do not overlook the emotional and active aspects of learning.

Connecting the head to the heart to the hand – Te Akomanga

The medium is the message

The diagram does not indicate what medium should communicate the historical narrative. In what ways can we express histories today? People can speak, sing, or perform history. Artist’s draw, carve, or film stories from the past. While new formats such as podcasts are becoming popular for packaging history, a preference for written accounts persists. For most senior students, the preferred medium remains an essay.

To accept one’s past – one’s history – is not the same thing as drowning in it; it is learning how to use it. An invented past can never be used; it cracks and crumbles under the pressures of life like clay in a season of drought.

James Baldwin, The fire next time (1963)

Silences in history

What about omissions or silences, things people do not mention, gloss over or simply forget, lost in the stream of time? Michel-Rolph Trouillot has shown how power works to produce history. He notes four crucial moments where silences enter the process of historical production:

- the moment of fact creation (the making of the source)

- the moment of fact assemblage (the making of archives)

- the moment of fact retrieval (the making of narratives)

- the moment of retrospective significance (the making of history in the final instance - e.g., Anzac commemorations).

Trouillot reminds us that any historical narrative is a bundle of silences: ‘Facts are not created equal: the production of traces is always also the creation of silences.’ [3]

Archivist and author Jared Davidson, recognises Trouillot’s moment of fact assemblage described above. Davidson agrees that archivists are not neutral gatekeepers of the truth. Archivists, like historians, make judgements on promoting and demoting aspects of history. Power mediates the historical relationship between past and present.

Using metaphors to describe history

Magnifying glass

It can be tempting to think of history like a magnifying glass. Historical evidence is examined closely, allowing the past to come into focus, neatly framed and in plain sight, with even minutiae writ large. This is true in a sense – history does bring the past into focus.

But it is not a straightforward single story.

Kaleidoscope

History is like a kaleidoscope – fractured and partial, its coloured crystal patterns shifting and changing the moment you twist it. The subject and the context are both intimate parts of the pattern, so that if we take turns looking through the kaleidoscope, we are likely to glimpse different configurations. Each turn constructs new, ever-evolving shapes.

Wānanga | Discussion for younger students

- It would be brilliant to have access to a physical magnifying glass and a kaleidoscope so students can play and experiment with them.

- Using the magnifying glass metaphor, describe how history has detective-like qualities: hunting down evidence and looking closely to find out about a person, place, or thing, accumulating evidence steadily until you have a clearer picture.

- Pass the kaleidoscope around the class (or look at patterns online), allowing students to describe or draw their own patterns. Compare these patterns, paying attention to the similarities and differences that emerge. These patterns are like history – never just one thing, and sometimes conflicting or competing ‘contested histories’.

- Ask students: If someone wrote the history of your life so far, what evidence would it be good for them to use, and why?

- Encourage students to think up questions they could ask if they were interviewing someone about their life.

Wānanga | Discussion for older students

- What do we know about the magnifying glass and the kaleidoscope? What is the history of these objects?

- How could you use these objects to describe history?

- What is truth?

- Can we ever know the truth about something?

- What is subjectivity?

- What do you think the purpose of history is?

- Complete the sentence: History is …

Oral history guide – NZ History

Wāhi: place-based education – Te Akomanga

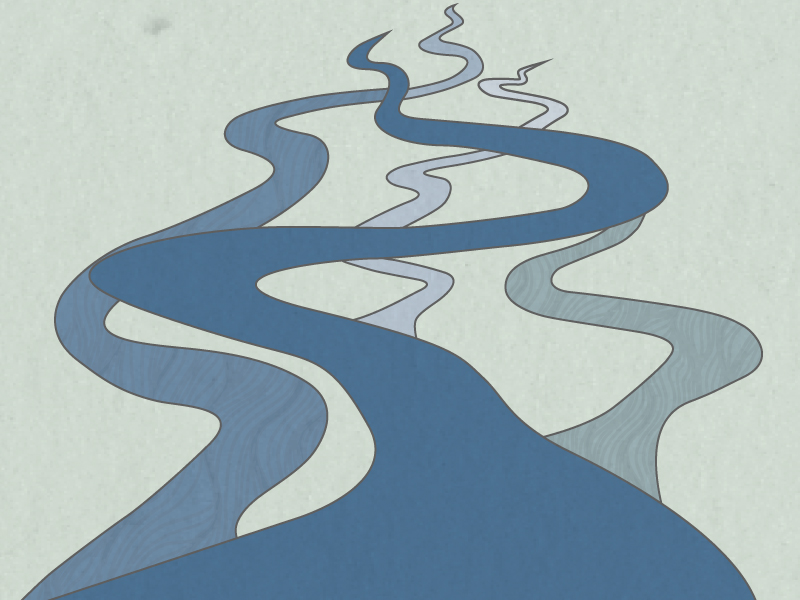

Water as a metaphor for history

E. H. Carr likened the past to a vast and often inaccessible ocean. So too did Jacob Burkhardt, who felt the challenge and weight of history when he compared it to going to sea in a boat he did not trust: ‘As soon as we become aware of our position, we find ourselves on a more or less rickety ship, driven on one of a million great waves.’ [4]

Fernand Braudel also compared history to an ocean and was interested in analysing its depths. For Braudel, the deepest layer was humans’ relationship with the environment, which involved slow change, constant repetition, and recurring cycles. Big history, the longue durée. Braudel’s second layer involved the swelling currents of social history, a history of groups and groupings. The top layer was a history of events and individuals, transient ripples, and waves on the surface of a vast and deep expanse of water.

Fish metaphor

History professor Jill Lepore uses a fish metaphor to illustrate to her students the importance of questions, evidence and planning when writing history. See How to Write a Paper for This Class (PDF, 75KB)

It makes sense that water can be a descriptor for history. We are the blue planet, and the human body is around 60% water. As Teresia Teaiwa so eloquently said: ‘we sweat and cry salt water, so we know that the ocean is really in our blood’. [5] Water is a connector, forever evaporating and condensing between earth and sky. The regeneration of the water cycle is an apt metaphor for the way history connects and moves us between time and place, the past and the present flowing in dialogue through the ages. History is a way for us to come into a deeper relationship with ourselves.

Ngā Uruora

For an ecological history of Aotearoa New Zealand see Ngā Uruora, by Geoff Park. This history is also available on Radio New Zealand.

The braided river is a relevant metaphor for history. Aotearoa New Zealand has stunning braided awa (rivers), such as the Rakaia. The braids illustrate the interweaving of analysis and storytelling in history, and their multiple water channels represent the different perspectives of these stories. These channels can be dominant or diverge to form ‘counter-narratives’ that also tell powerful stories.

While the Rakaia is an important touchstone from the Canterbury region, in Wellington, culverted streams provide an effective metaphor for silences, hidden stories and marginalised perspectives people have covered up or ignored.

Notes

[1] Raphael Samuel, Theatres of Memory: Past and Present in Contemporary Culture (1994), p. 15.

[2] Edward Hallet Carr, What is History? (1961).

[3] Michel-Rolph Trouillot, Silencing the Past : Power and the Production of History (1995), p. 29.

[4] Jacob Burkhardt, Historische Fragmente (1957).

[5] Epeli Hauʻofa, We are the Ocean: Selected Works (2008).

Community contributions