The public service was the engine of New Zealand’s military war effort between 1914 and 1918. It took charge of signing up – and later conscripting – men for service abroad, training them, clothing them, housing them and transporting them to the northern hemisphere, where they became the responsibility of the British military.

While the Defence Department was the arm of the service most directly responsible for getting men to war, the Census and Statistics Office, the Post and Telegraph Department and the newly formed Munitions and Supplies Department played essential roles in supporting the process. By the end of the war they had recruited, trained, equipped and transported nearly 100,000 men to the northern hemisphere. This article examines how this massive task was accomplished.

Preparing for war

By 1914, New Zealand had been actively preparing for war for five years. In Europe, the darkening geopolitical skies of the century’s first decade had led all the major powers to gear up for a conflict. Since 1907 Britain had been lining up its dominions to assist in a major war, and New Zealand agreed to play its part. From 1909 it undertook a major reorganisation of its military forces to bring them into line with British practices and formations so its fighting units would slot seamlessly into a British expeditionary force.

New Zealand needed to transform its loose network of local volunteer units into a single Territorial Force with a clear chain of command and manned through a system of compulsory military training. The Imperial General Staff lent British officers to New Zealand to help the dominion reorganise its defences, and to make detailed preparations for a major war. Mobilisation and home defence plans were drawn up, and a large training and education infrastructure was created.

This ambitious and complex task fell to the Defence Department, which was reorganised into a national command along the lines of the British War Office. Defence Headquarters in Wellington’s Buckle St supervised four district commanders, who in turn controlled a series of smaller sub-districts (there were initially 16 of these, and 21 by 1916). The 1912 Public Service Commission (Hunt) Report described the department as ‘an entirely new organization’ following the 1909 reforms.

The Defence Department had a highly unusual leadership structure. It was headed by senior military officers subject to military discipline and regulation, not by traditional public servants. Lieutenant-General Alexander Godley was both General Officer Commanding the New Zealand Forces and (effectively) the administrative head of the department. To further confuse matters, many of the department’s clerical staff were conventional public servants working under the more lenient but less remunerative Public Service Regulations. It was a sometimes awkward hybrid of two quite different working cultures and traditions. This did not prevent Defence performing its functions as a department of state, and was probably a difference of style as much as substance.

The outbreak of war

The pre-war preparations allowed the Defence Department to quickly and efficiently create an expeditionary force in 1914. A 1400-strong Samoan Expeditionary Force was despatched almost immediately, and volunteers flooded Defence Department offices in the hope of becoming one of the 8000 men needed for the Main Body of the New Zealand Expeditionary Force (NZEF) that was expected to be sent to Europe.

The department obtained much of the necessary equipment from the Territorials, and moved quickly to purchase other items or find people willing to donate them. Each military district accommodated its section of the Main Body in a temporary camp while they waited to sail for the front. Refresher training filled what turned into two months of waiting before the men boarded newly fitted-out troopships.

The department had managed to contract enough vessels from the main shipping companies to transport the Main Body. These ships were stripped and fitted out to accommodate troops and horses, a process which would have to continue if reinforcements were to be supplied. In late 1914 the department established a Transport Board, chaired by its director of movements and quartering, which was responsible for chartering suitable vessels and getting them fitted out to carry troops. Most of the ships were refitted at the Union Steam Ship Company’s yard at Port Chalmers, where the old fittings were stripped out and hammocks slung up for the men.

Territorial Force training would continue throughout the war, but now the department would have the far greater additional challenge of finding, equipping, training and transporting regular drafts of reinforcements to keep the expeditionary force up to – from early 1916 – divisional strength. The pre-war plans had worked well, but maintaining the supply of reinforcements would test them to the utmost.

The 1915 crisis

Keeping the NZEF reinforced was a straightforward business in late 1914 and early 1915, when volunteers were still rushing to enlist, but managing the process grew more difficult as the number of men needed grew. Every man who donned a uniform had to be provided with basic military training, clothed, fed and transported, and much would go wrong before the Defence Department mastered this massive task.

The task of despatching reinforcements should have dropped to the manageable proposition of supplying two-monthly drafts of about 776 men after the Main Body left. The department opened a national training camp at Trentham in Hutt Valley. This was designed to accommodate no more than 1500 men in tents, but by November 1914 the government had already raised the size of reinforcement drafts to 3000 every two months. The number of troops in camp at any one time crept up steadily in the following months, as new units for the expeditionary force were established.

By May 1915 Trentham Camp housed 7000 men, and its basic facilities were soon overwhelmed. The ground turned into mud, and the manufacturers supplying uniforms and other gear were unable to keep pace with the ever-increasing numbers. Disaster struck that winter, when 27 recruits at Trentham died of infectious disease.

The Trentham crisis created a major scandal and undermined faith in the Defence Department at a time of public anxiety about the growing Gallipoli casualties. In early July, Defence Minister James Allen ordered the evacuation of the camp. Thousands of men were moved to a string of impromptu canvas camps during heavy winter rains.

The Defence Department quickly began rebuilding Trentham and constructing a larger camp at Featherston to share the load. The Public Works Department assembled massive teams of carpenters who assembled the camps within a few months under the supervision of the Railways Department’s E.H. Hiley.

The overhaul of the camp system was supported by the creation of a Munitions and Supplies Department to relieve some of the Defence Department’s growing responsibilities. Munitions and Supplies completely revised the process of purchasing uniforms and stores, signing up manufacturers to a new system which quickly relieved the camp shortages. It also supplied food, medicine, forage and other items to the camps and troopships.

The standing camp system

Featherston Camp and the remodelled Trentham Camp were extensive and modern facilities. With a combined capacity of 17,000 men, the two camps would provide for all foreseeable needs and train the bulk of the recruits for the remainder of the war. Each covered hundreds of acres, and maintaining these pop-up towns was a logistical exercise without precedent in New Zealand history.

The two camps included a wide range of buildings, training grounds, rifle ranges and infrastructure such as roads, railways, electricity, water supplies and underground drainage. Guardhouses at the gates kept the public out, and nearby roads and private homes came under military control.

Both camps had their own dedicated staffs. By 1918 Trentham had 967 staff and Featherston 1183, only a small proportion of whom were actually involved in training. They were a mixture of clerical workers maintaining records and pay arrangements; quartermaster’s staff responsible for provisions and food; workshop staff maintaining camp equipment; and others responsible for maintaining weapons and buildings, transporting the men and looking after their teeth and general health.

Most of the camps’ food was purchased locally from farmers and merchants. Both camps set up pig farms to dispose of food scraps and raise some income, while huge incinerators burnt their general rubbish. By the end of the war the government had spent £227,388 14s 2d on the two main camps (equivalent to more than $23 million in 2015).

The ‘standing camp’ system was completed by two much smaller specialist camps. From 1915 medical recruits trained at Awapuni Camp, at Awapuni Racecourse in Palmerston North. Narrow Neck Camp, on a military reserve near Takapuna, accommodated Māori, Pacific and Tunnelling Company recruits.

The paper trail

Keeping track of all the men who had enlisted, entered camp, departed overseas and been wounded, killed or demobilised was a massive task. By the end of 1914, 12,500 men had left the country. The figure climbed to 30,000 by the end of 1915, 61,000 by the end of 1916, 88,000 by the end of 1917 and nearly 100,000 by the end of the war. The department maintained a separate personnel file for each soldier. This outlined his postings to different units, his health and casualty status, his misdemeanours and promotions, his movements, and so on.

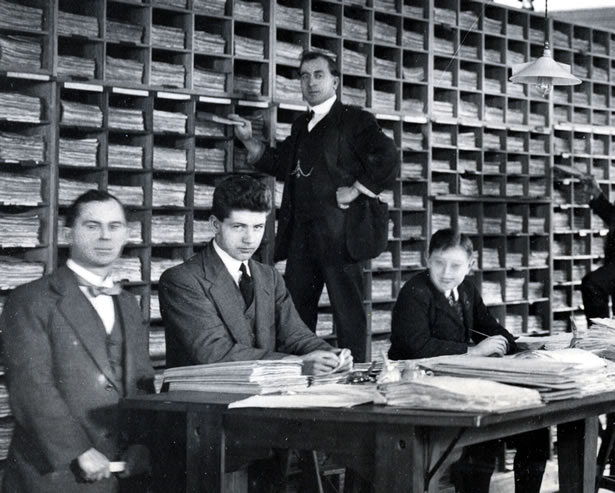

The challenge of maintaining this system grew as more and more men were sent overseas. Each file had to be accessible in order to document the movements of each individual, and the scale of this process was soon far beyond the capacity of the five clerks who had maintained all the Defence Department’s records at Buckle St in 1914.

The job of processing the Gallipoli casualty lists quickly forced an expansion of staff, and in June 1915 the department rented an attic office in Brandon St in downtown Wellington to house its ever-expanding Records Office. Files lined all the walls. ‘Every name has to be checked carefully, for mistakes are not allowed in this branch’, wrote the Sun’s reporter; ‘telegrams are sent to the next-of-kin of the wounded, sick, or killed men before the lists are handed to the newspapers.’ [1]

The ballooning work prompted the department to create a separate ‘Base Records Branch’ in November 1915. This soon moved into a third, larger office, which it again quickly outgrew. In March 1916 the department drew up plans for a purpose-built two-storey Base Records building lined with corrugated iron that was erected behind Parliament Buildings. A large public enquiries area occupied much of the ground floor space, while a pool of typists replied to about 500 letters from anxious relatives each day. At the time of its completion the building seemed massive and adequate for all conceivable future needs, but within a year its record room had been enlarged and further extensions were in the works. Base Records’ staff numbered 160 in mid-1917 and 230 a year later, by when more than 1000 letters were being received on a typical day.

National registration

Recruitment all but took care of itself until the spring of 1915. Initially a steady stream of men presented themselves at the local Defence office for consideration. From early 1915 they filled out an enlistment form at their local post office and sent this in. A medical examination identified those who were fit to fight. Each military district had a quota to fill, and each group of recruits were called to camp in time to fill the next reinforcement draft.

This system worked well as long as men kept coming forward, but the number of volunteers was starting to fall short by the winter of 1915. In October the government introduced National Registration, whereby all men of or near military age had to fill out a card giving personal particulars and indicating their willingness to serve in the NZEF. This exercise would provide the government with information about the number of potentially eligible men who had not signed up.

Government Statistician Malcolm Fraser was entrusted with the task of compiling the register. In October/November 1915 Post and Telegraph staff personally delivered registration cards to every household in the country. A staff of 244 clerks processed the cards to produce the desired statistics. Three hundred rolls listing the military-aged men in each county were supplied to local volunteers, who knocked on the men’s doors to urge them to enlist.

Conscription introduced

National Registration – and the associated campaign – failed to solve the recruiting crisis, and by early 1916 the government was moving towards conscription. Conscription had been introduced in the United Kingdom – with the exception of Ireland – in January. The Military Service Act passed on 1 August 1916 established that any man of military age could be balloted for active service abroad, subject to an appeals process and passing a medical examination. The compilation of the National Register, with its voluminous paperwork and interdepartmental co-operation, had suggested just how complicated the recruiting process would soon become.

Fraser and his team were once again entrusted with managing the exercise, which this time had an overlay of legal process and public scrutiny. The new system was based on the National Register, from which clerks removed the cards of those who had already enlisted or were otherwise ineligible. The cards were divided into classes - single men would be called up before married men – and by district so that local quotas could be maintained. Working on the assumption that many of those balloted would be medically unfit, the authorities planned to call up three men for every one the NZEF needed.

The Defence Department bombarded the public with information to ensure no one could claim ignorance of his legal obligations. It placed posters in every post office, police station and railway station; at wharves, shipping offices, shops and factories; and in tramcars, railway carriages and coastal vessels. In the cities, post office staff hand-delivered the posters to every home. They were even projected from lantern slides onto cinema screens.

The ballot

In 1919, Director of Recruiting Captain David Cossgrove wrote of the first ballot: ‘For the first time in the history of the English speaking peoples of the world the single men of military age of a British community found themselves subject to a lottery, the prizes in which might be anything from Home Service in New Zealand to death on the battlefield.’ The publication of the first list of names ‘was awaited with breathless interest by all, and with trepidation by some.’ [2]

Fraser supervised the first ballot of just over 4140 men on 16 November 1916. The process took more than 20 hours. Choosing each man involved rotating two drums containing marbles. The marble he chose from the first drum directed him to a drawer, and the marble from the second drum denoted a card in this drawer. Each card was turned upright in the drawer before a magistrate removed it and attested that it had been fairly balloted. The mayor of Wellington and a representative of the local Trades and Labour Council were present as observers on behalf of the public.

Fraser’s staff quickly assembled lists of the balloted men, despatching one set to the pool of typists in the Defence Department’s new Recruiting Branch. The branch issued each man with a notice stating that he had been balloted and ordering him to report to camp on a certain date. It was a lengthy process carried out under crippling time constraints, since the men had to be delivered the notices in time to appeal within 10 days if they wished to. The branch typically received the ballot cards at 8 or 9 on a Friday evening and worked in shifts for the next 36 hours to complete the job.

The Recruiting Branch grew from five staff in mid-1916 to more than 230 by the end of the war. Cossgrove remembered that they developed systems by trial and error. What they were doing was ‘without precedent in the military history of the Empire. Everything was new’. [3] The growing scale of the task forced the branch out of headquarters and into a series of commercial buildings in the city, each of which it outgrew before finally settling in Clarkson’s Building in Taranaki St.

The ballots were held almost every month for the rest of the war. Like the Base Records process, they generated a huge quantity of paperwork. Fraser noted after the war: ‘The cards in the Register, which weigh approximately 2¾ tons, if placed end to end would extend over 38 miles, and if opened and spread out would cover an area of some 18,765 square yards.’ [4]

Enforcing conscription

The introduction of conscription complicated the recruiting process considerably. For one reason or another, many conscripts did not want to go to war. Under the conscription system they were able to appeal on the grounds of ‘undue personal hardship’, because their departure from their job would be ‘contrary to the public interest’, or on the basis of tightly defined religious objections. A Military Service Board was set up in each district to adjudicate upon appeals.

The government recognised that the key to making conscription work would be to punish those who tried to evade the system. Under the Military Service Act, balloted men who failed to present themselves for service could be imprisoned with hard labour for up to five years, and businesses could be prosecuted for employing them. Men who failed to enrol in the first place were subject to fines and imprisonment. Fraser recalled that these penalties were ‘drastic and in every case … immediate proceedings were instituted.’ [5]

Those who were legitimately enrolled for the ballot were issued by the Census and Statistics Office with a ‘certificate of enrolment’ which they could present as proof of meeting their legal obligations. These were given to each man at his local post office so the staff could ensure he really was who he said he was. It was worth carrying this document on your person, as section 44 of the Act empowered the police to stop any man ‘who may reasonably be supposed to be of military age’ and demand proof of enrolment. From July 1918 they could arrest anyone not carrying their papers on the spot and imprison them for 48 hours.

The government had been gradually clamping down on the movements of military-aged men since late 1915. In July/August 1916 it banned men as young as 15 from leaving the country without a permit. From February 1917, Customs and Marine Department officers interviewed male British subjects of military age on their arrival in New Zealand. Anyone planning to stay for more than three months would have to become a permanent resident. From December 1917, the police were empowered to arrest and deport any man arriving from an Allied country in which conscription was in force.

Balloted men who failed to report for service on the appointed date presented the greatest challenge. They fell into two main categories: those who turned up for their medical examination but did not go to camp, and those who never appeared at all. The Recruiting Branch gave these men the benefit of the doubt, but when their district office was unable to find them their cases were referred to the new Personal Services Branch.

Created in February 1917, Personal Services investigated each case and reported back on those men it considered to be deliberately avoiding service. By March 1919 it had investigated 10,737 men, of whom 1294 remained at large. Of those located, 2211 men had been found to be eligible for service, 580 had been arrested for breaches of the Military Service Act and 1133 warrants were outstanding. District Defence offices arranged arrests with the police.

Arrested defaulters passed into military custody and were imprisoned after a court martial (being balloted put them under military jurisdiction). They served their sentence in either a military or a civilian prison, and at its conclusion they were drafted into the NZEF or, if they were medically unfit, into a home service role.

The end of the war

At the end of the war, A.W. Robin, the General Officer Commanding, was satisfied that the Defence Department had performed well. ‘The Expeditionary Force … was fully and efficiently maintained’, he wrote, ‘having at no period during the war been below strength, or short of equipment, Reinforcements, and supplies.’ [6] This assessment glossed over much of the strain and complexity of the war years, but was broadly accurate. The department and those assisting it had adapted and co-operated to efficiently manage the difficulties of wartime administration.

The Defence Department was now able to return to a peacetime footing, rapidly dispensing with large numbers of temporary staff and wartime branches for which there was no longer need. It learnt lessons from its wartime experiences, and soon moved to reconfigure its practices, its camp system, and its Territorial Force arrangements. It expanded its rehabilitation system for returned servicemen and helped manage the medical problems of those who had returned injured. It continued to search for those who had refused to serve. In May 1919, Defence published a list of 2600 defaulters, all of whom were deprived of their civil rights for 10 years and banned from returning to New Zealand for the same period if they had been abroad in December 1918.

Further information

This article was written by Tim Shoebridge and produced by the NZHistory team. It was commissioned by the State Services Commission. A fully footnoted version is available to download as a pdf here.

Primary sources

The annual reports of government departments for the years 1914-19 published in the Appendix to the Journals of the House of Representatives provided most of the information for this article. See also Statutes of New Zealand and the regulations published in the New Zealand Gazette. Key information was also drawn from the following reports at Archives New Zealand, Wellington:

- David Cossgrove, ‘Recruiting 1916-1918’, AD1 712 9/169 pt 2

- Malcolm Fraser, ‘War work of the Census and Statistics Office’, IA1 1652 29/125

Books

- Imelda Bargas and Tim Shoebridge, New Zealand’s First World War heritage, Exisle Publishing, Auckland, 2015

Notes

[1] Sun, 16 June 1915, p. 5

[2] David Cossgrove, 'Recruiting 1916-1918’, AD1 712 9/169 pt 2, Archives New Zealand, p. 24

[3] Cossgrove, p. 10

[4] ‘War work of the Census and Statistics Office’, p. 14, IA1 1652 29/125, Archives New Zealand

[5] ‘War work of the Census and Statistics Office’, p. 13, IA1 1652 29/125, Archives New Zealand

[6] Defence Department annual report, AJHR, 1919, H-19, p. 1

Community contributions