Ballot boys

More families were hit with the unavoidable reality of the war in the middle of 1940. For the first 10 months of the conflict, the men who enlisted had been volunteers and the patriotic recruitment campaign had been successful: by June 1940, nearly 60,000 men had volunteered for military service.

After the first flush of enthusiasm, however, recruitment had slowed. A steadier supply of men was needed to keep a fighting force in the field, and in July 1940 the choice of whether or not to sign up for war ceased to exist. The introduction of conscription meant that every man between 19 and 45 was liable for service. No one could escape the net as the government trawled for men. At the very beginning of the war, the Social Security Department drew up a list of 'every male resident in the Dominion over the age of sixteen', anticipating the younger men becoming eligible to serve in the future.

In the five years that conscription was in force 306,000 men were called up. Although conscription was run on a ballot system, men with the fewest commitments were first in line. The young and single were more likely to be called up than older, married men. Others were exempt if they worked in essential industries such as war-related production and services. War veterans, invalids and those in hospital or prison were not liable. Māori were exempt from conscription and continued to serve only if they volunteered.

Home work

While thousands of civilian men became soldiers, some had to stay home and work. From the beginning of the war the government designated some industries and occupations as 'essential'. These included power supply, shipping, freezing works, timber mills, mines and munitions factories, but essential industries were never clearly defined: 'The whole process of selection in fact tended to be short-term and arbitrary in its application.' At different times during the war the list included tobacco processing, footwear manufacture, food canning and soapworks. Men working in essential industries could be exempted from military service by appealing to a panel representing both their interests and those of their employer. Usually it was employers who lodged appeals.

By early 1944, 180,000 New Zealand men were employed in essential industries. Those working in factories and other production were joined by policemen, firemen, railwaymen, doctors, chemists, magistrates, ministers of religion and Members of Parliament. And more than 15,000 men stayed working in public service departments.

In some communities resentment bubbled up towards men who were 'reserved' from being sent to war. The appeal system came in for criticism particularly from those who lived with the anxiety of having sons, brothers and husbands overseas. For the men themselves, staying home could be uncomfortable. One fit man in an essential job suggested that:

retained men should form their own association … its coat of arms showing a muscular worker 'held back by an obvious official with a spool of red tape and the president of the RSA [Returned Services Association] attacking our unprotected rear with an Army boot'.

Such wry humour was understandable. In public, attitudes towards the men who were exempted were often harsh and judgemental. Any fit-looking young man was fair game.

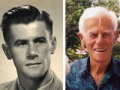

For those who had not chosen to stay out of action, the discomfort could be acute. Rangi Utiku, who was rejected by the army on medical grounds, was 'downhearted' and withdrew from social contact throughout the war. Others, like Ross Cooper, whose father appealed against his conscription and kept him home on the farm, felt embarrassed. He, too, spent the war with his head down, unwilling to risk the finger-pointing.

In spite of his unease, Ross Cooper's wartime work was recognised as crucial to the war effort. Food production – not only for New Zealanders, but also to supply the people of Britain – was so critical that it has been described, after military involvement, as 'the other leg of New Zealand's war effort'. Although farming was never declared an essential industry, appeals against the conscription of men working on the land were often successful. By 1945, the last year of the war, farmers made up a third of the men who had been kept out of the armed forces to work at home. The government protected farm production, even to the extent of temporarily releasing men who had just been called up, to help with seasonal work when needed. In an informal arrangement, the army also helped farmers by 'lending men for harvest work.'

'The manpower'

The government grip on civilians' lives tightened further at the beginning of 1942. Thousands of men leaving for war had left job vacancies in factories and other workplaces. To fill the gaps, 'manpower' regulations came into force. Now workers could be directed where they were needed. Compulsory registers were set up and in 22 centres throughout the country the Manpower Office became the hub of working life.

At first, all men between 18 and 49 had to get their names on a register. As jobs in essential industries grew, the net was cast wider, and over the next two years its scope expanded to men up to 70 years old. When the regulations were introduced, there was 'some hesitation' in making women register for manpower jobs. Only those who were 20 or 21 had to sign up. By 1944 this reluctance had disappeared, and all women between 18 and 40 were liable to work where directed.

Women who cared for children under 16 were exempt, but they were encouraged to volunteer if they could arrange childcare. For a while, married women were exempt too, but by the end of 1943 a wedding ring made no difference to the local manpower officer. For some women, like Riria Utiku, this came as a shock. She was also unhappy about being told she would be sent to either the woollen mills or a tobacco factory and managed to get herself a job in the public service instead. She was not alone in resisting the manpower officer and criticisms were made at the time that women were being 'forced into low-paid and unsatisfying employment'.

In the 1940s making women do any sort of paid work was a break with tradition. It went against the belief that 'women's lives were best focused on private family and domestic matters'. By the end of the war, though, 38,000 women had been sent to work where the government directed. They were invariably paid less than men. In October 1942 minimum weekly rates were fixed at £5 10s for men and £2 17s 6d for women. There was little resistance to the inequality. Sheila Smith worked in an orchard for 'about half' the rate of the men alongside her but felt there was nothing she could do about it.

That's the way it was. Because you were a woman you got much less than the men. That was the accepted thing, that you are a woman and you just held out your hand and got your pay packet and were grateful for it.

By the end of the war, more than 176,000 people were working where the manpower officer had sent them. The government retained its right to direct people into jobs until June 1946, nine months after the war ended.