This essay written by Melanie Nolan and Penelope Harper was first published in Women Together: a History of Women's Organisations in New Zealand in 1993.

The Dunedin Tailoresses' Union (DTU) was New Zealand's first women's union. [1] With a membership fluctuating between 350 and 1400, it fought to improve the lives and working conditions of Dunedin's wage-earning women, and helped a wide range of clothing workers through its close association with the Federated Tailoresses' Union of New Zealand (FTU), the Department of Labour and the industrial labour movement.

In 1888 and 1889, lectures and sermons by the Reverend Rutherford Waddell and an investigation by the Otago Daily Times (ODT) brought the working conditions of Dunedin's female clothing factory workers to public notice. Although other women workers faced worse conditions, the tailoresses captured attention: their plight indicated that the industrial evils supposedly left behind in the 'Old World' had not only taken hold in the new, but were threatening the physical and moral health of the nation's future mothers.

At a meeting on 14 February 1889, local labour leaders and respectable citizens – including Waddell, W. Downie Stewart, and ODT reporter Silas Spragg – formed a committee to campaign for improvements. When employers refused to negotiate, the committee formed the Dunedin Tailoresses' Union on 12 July 1889. Under threat of strike action, local employers soon agreed to reduce working hours (although some women continued to take work home), and to raise wages by at least 2 percent, and in some cases as much as 40 per cent – a significant accomplishment for the union. Even so, the 1890 Sweating Commission heard complaints that the new rates were still not high enough for women to support themselves, and many tailoresses had to rely on their parents.

DTU members were mainly young single women; male clothing workers were invited to join, but few came forward, and in 1891 the union restricted itself to women. However, men were prominent at first as office-holders: Waddell was the first president and John A. Millar of the Seamen's Union was secretary. A succession of male presidents followed, most with close ties to other unions. [2] But by June 1891, when Harriet Morison succeeded Millar as secretary, she was supported by thirteen other women on the executive. She was followed by Ada Whitehorn, Selina Hale and from 1908 to 1943, Jane Runciman; these women, all single, negotiated the awards and ran the union.

The DTU quickly acquired assets, set up committees and provided for its members' well-being, obtaining a meeting hall, reading room and benefit committee, and planning a seaside convalescent home. It is estimated that over 1000 people travelled to the union's first annual picnic at Purakanui in 1890. In 1892 it formed a social committee and bought a piano, aiming to turn the monthly meetings into social occasions. Morison understood the importance of public relations, and actively fostered links between women wage-earners, the community, and the media. [3]

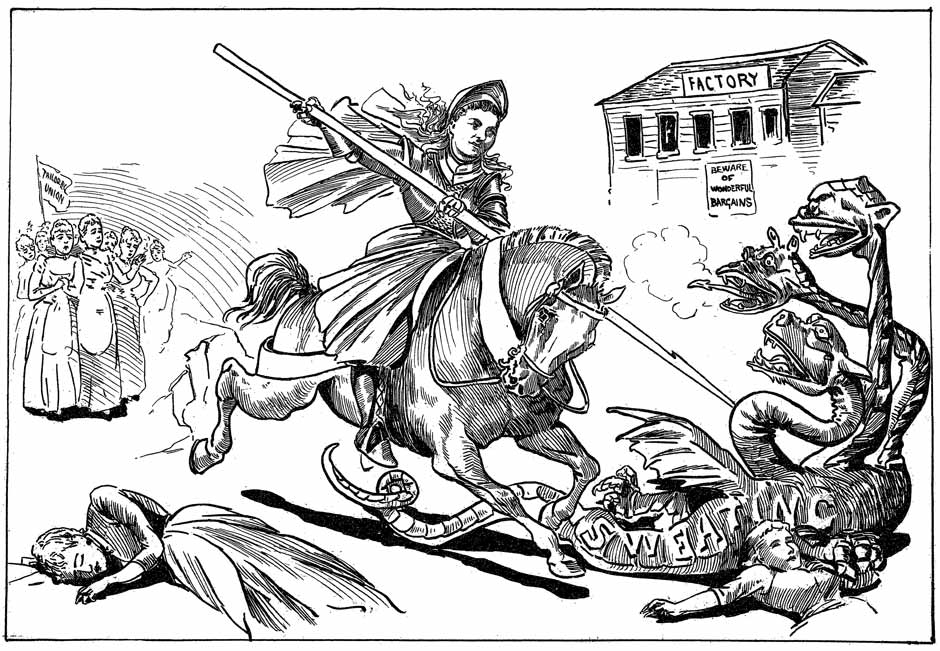

William Blomfield's 1892 cartoon shows a woman knight on a charger lancing the sweating monster, while a group of women holding a Tailoress's Union banner walk behind the knight in support. Ref: H-713-106, Alexander Turnbull Library.

The DTU was a feminist industrial organisation with three major concerns: organising women workers nationally, promoting women's training to ensure tailoresses were skilled workers and were paid appropriately, and supporting legislation which was in the interests of women workers. In its first three years it donated over £250, and Morison's services as organiser, to the struggling Auckland, Wellington and Christchurch unions. For a long time the only tailoresses' union with a full-time secretary, it was to become the backbone of a national federation. The Federated Tailoresses' Union held its first conference in Christchurch in July 1891. From 1895 it sought a national award for factory tailoresses; this was achieved in 1898, under the new arbitration system. Auckland, the last union to adopt the rates won by Dunedin, joined the federation in 1909, and the FTU finally negotiated a uniform national award in 1910.

Meanwhile the DTU concentrated on the still unorganised women making clothes to individual order, and in 1898 it negotiated an agreement with nearly 50 Dunedin bespoke tailoring firms. Besides supporting the fledgling federation, and a Southland branch, the workplace issues it dealt with included policing wage rates, debating the proportion of apprentices to skilled journeywomen, seeking the abolition of piecework, winning preference for union members, ensuring there was fair distribution of work when the Depression brought short hours, and fighting against the introduction of the 'team system' or machinery which sub-divided labour during World War II.

As Morison's and Whitehorn's involvement with domestic workers shows, the DTU was keen to help organise and educate other working women, and to raise women's status generally. It lobbied so actively for women's suffrage that two-thirds of the 4000 signatures collected in Dunedin for the first nation-wide suffrage petition of 1891 were from working women. The second generation of DTU activists supported National Council of Women (NCW) campaigns to remove women's civic disabilities. Runciman, the DTU's delegate to the NCW and a labour union representative on the King Edward Technical College board, became one of the first women justices of the peace in 1928. However, her calls for greater unionisation of women were largely unproductive, although she was one of three women elected to the national executive of the United Federation of Labour in 1918.

The DTU was committed to labour legislation and state intervention; from 1890 it campaigned for female factory inspectors, and after 1900 the Department of Labour employed Morison and Hale as inspectors and Women's Employment Branch officers. When six months of negotiations between the FTU and Auckland employers fell through in 1892, the DTU again turned to the state and lobbied for compulsory conciliation. Thereafter it scrutinised every amendment to factory legislation, lobbying local MPs and their circle. Throughout, it strove to be conciliatory rather than 'antagonistic to employers', and its active members were keen to 'carefully and skilfully avoid all trouble themselves'. [4]

The union struck trouble in 1895. Bad weather meant that two picnics planned by Morison were a financial disaster, so she organised a carnival to wipe off debts and raise funds. She put the carnival bank account in her name, but did not keep proper books. In 1896 members of the DTU executive committee accused her of embezzling union funds, and she resigned. The incident resulted partly from tensions within the union leadership, but it may also have involved a challenge to Morison's wide-ranging feminist approach: certainly the DTU became less active in issues beyond the workplace after she had gone. Its early exuberance had been costly; the Christchurch union had to shoulder responsibility for the federation in the late 1890s, and the DTU was still in debt to Christchurch in 1909.

In 1921 the New Zealand Federated Clothing Trade Employees Union succeeded the original 1891 federation, and in 1928 moved its headquarters from Dunedin to Christchurch. Its secretary, John Roberts, amalgamated all three Christchurch clothing unions into one regional union in 1935, and pressured other regions to follow suit. The DTU executive strongly opposed Roberts, but R.A. Hill, secretary of the Otago and Southland Tailors' Union, supported him. The South Dunedin branch of the Labour Party joined in, accusing the DTU of being old-fashioned and slow to support the party. When a postal ballot of women was held in 1945, 66 percent of the 1068 votes returned were for amalgamation with 174 male tailors, cutters and pressers in a new Otago and Southland Clothing and Related Trades Union.

From June 1945 the DTU ceased to exist. The old DTU executive had wanted its successor to consist of four males and eight females, with a female secretary and president, reflecting the preponderance of women members, but this was not accepted; very few women attended the first combined meeting, and men dominated the new union for at least the next twenty years.

Melanie Nolan and Penelope Harper

Notes

[1] There had been some organisation of women in tailoring workplaces in the 1880s. The Kaiapoi Sick and Accidents Benefit Society had existed from 1884, with a male president and general committee, but a largely female visiting committee (though it was not formally organised). The women involved went on to play a prominent role in the Christchurch Pressers' Union. See, for example, Lyttelton Times, 25 January 1893.

[2] They included David Pinkerton, Sydney Brown, Patrick Hally, William Hood and, from 1906-45, J. T. Paul.

[3] Community involvement was high; for instance, the Knox College singing classes assisted at the DTU convalescent home fundraising concert, businesses made substantial donations, and Freeman Kitchen, editor of the Globe, published all he could on the union.

[4] ODT, 24 July 1890; 30 December 1890.

Unpublished sources

Christchurch Tailoresses' and Pressers' Union executive minutes, 1891–1935, Canterbury University Library

Couling, D. F., 'The Anti-Sweating Agitation in Dunedin, Christchurch, and Auckland, 1888–90', BA (Hons) essay, University of Otago, 1973

Dunedin Tailoresses' Union collection, Hocken

Harper, Penelope, 'The Dunedin Tailoresses' Union, 1889–1914', post-graduate diploma thesis, University of Otago, 1988

J. T. Paul papers, Hocken

Rodden, Mary C., 'Women and the Labour Movement, 1910–1918', BA (Hons) research essay, University of Otago, 1976

Tailoresses' Union Invercargill Branch minutes, 1920–1942, Otago Trades Council records, Hocken

Published sources

Globe, 1888–1893, McNab Collection, Dunedin Public Library

Paul, J. T., Our Majority: and the After Years 1889–1939, Some Dark Shadows and High Lights in Industrial History, Otago Daily Times and Witness Newspaper, Dunedin, 1939

Community contributions