This essay written by Geraldine McDonald was first published in Women together: a history of women's organisations in New Zealand in 1993. It was updated by Helen May in 2018.

1889-1993

The establishment of the free kindergarten movement in Dunedin in 1889 and the playcentre movement in Wellington in 1941, [1] the consolidation of the childcare movement in the 1960s, the emergence of Māori preschool movements in the 1970s and Te Kōhanga Reo in the 1980s, all related to one common task: educating and caring for children too young to be admitted to school. New Zealand women initiated, developed and supported these services. Their emergence, their forms, their general acceptance and their claims on the public purse can best be explained in terms of care rather than education. But unlike education, the issue of care has always been contentious, touching as it does on beliefs about the proper behaviour of women. Who should care for young children? Where should this care be carried out? What kind of care is best?

The free kindergarten, playcentre, and childcare movements were all at some time criticised on the grounds that young children should be cared for at home by their mothers. Only Te Kōhanga Reo, formed in 1982, seemed to escape such criticism. The common response to this argument was to stress the educational value of the particular service. However, their original rationales differed. The free kindergarten movement saw itself as a philanthropic endeavour, reaching out to help the children of the poor. The early mission of the playcentre movement was to provide women with relief from the care of small children; but this was not a generally acceptable purpose in the climate of the times, and it soon changed to educating women as parents. The childcare movement, unlike the other services, explicitly supported women's rights. Te Kōhanga Reo was conceived as an agency for preserving and reviving Māori language and culture.

Despite their differences, all these movements had a common outcome: offering women opportunities in the sphere of public life. Which women was determined in each case by class, race and the particular features of the movement. The early kindergarten movement recognised the talents of two categories of women: the wives of the well-to-do, and unmarried women of good education. The playcentre movement provided educational and vocational opportunities for women at home during their child-rearing years. The childcare movement accepted that women had the right to undertake activities outside the home and away from their children. The Māori movements drew on the knowledge and talents of older women, and provided Māori women with the leadership positions not always accessible to them in the longer-established services.

As enterprises involving large numbers of women, the movements for early childhood care and education were from time to time trivialised as 'women's work'. Although they provided services of particular benefit to women, they all welcomed the support of men, particularly on finance and building committees. In each movement women looked for men sympathetic to their cause, and often asked them to speak publicly for the movement, in order to make it more socially acceptable. All the speakers at the public meeting in March 1889 to gather support for the first Dunedin kindergarten were men. The first Nursery Play Centre Association committee, formed in Wellington in 1941, consisted of three women; however, they later co-opted two men to help them. This enabled them to make use of resources which men were more likely to have at their command, such as offices, staff and equipment: 'for years the committee met in Mr [Harry] McQueen's office and his staff did all manner of printing and duplication'. [2]

The characteristics of the family as a setting provided benchmarks across all services. Size of group, ratio of staff to children, and qualities of carer were measured against the concept of the family, with its 'free' 24-hour care. It was therefore doubly difficult for childcare workers to argue for professional training and an adequate salary.

If it was accepted that young children, or at least some young children, could legitimately be cared for outside their homes in early kindergartens when they were disadvantaged, or neglected; or in playcentres because their mothers would accompany them; or in Māori preschools because they would be cared for by the whānau, then the issue became how long they should be away from home. Sessional or half-day care became the dominant form of service. Even so, the fear that mothers might be 'dumping' their children in kindergartens and playcentres was at its height during the 1950s, when the theories of John Bowlby on the dangers of separating mother and child – 'maternal deprivation' – were having the most impact. A 1952 article claimed that kindergartens had been under fire because they did not take sufficient account of children's emotional needs; early playcentres had difficulty obtaining permission to use church or community halls. 'There was, in some quarters, strong opposition … from people who thought a woman's place was in the home twenty-four hours of every day.' [3]

Childcare incurred the greatest political and public opposition, because it allowed women sufficient respite from the care of their young children to undertake paid employment outside the home. Playcentres and Parents Centres both promoted the idea that separating a child from its mother before the age of two-and-a-half would put the child's mental health at risk. 'Separation' was interpreted as quite short periods of time, and no account was taken of the quality of care. For many years, such ideas made it difficult to get public support for the care of infants outside the home, except in desperate circumstances. As childcare began to gain some public support, the idea of family daycare – supervised care of small groups of children in private homes – was promoted, especially by those opposed to childcare.

The Kindergarten Movement

Objections to arrangements which allowed young children to be cared for outside their homes were by no means new. In New Zealand, individual creches and kindergartens were established early on, but did not spread to other sites. In 1879 a group of women in Dunedin tried to initiate a movement to provide crèches, but failed to gain sufficient support, and none was started. The WCTU established a kindergarten in Auckland in 1887; and in 1889 a second Dunedin group, which included some of the earlier women, successfully established a kindergarten there. Their stated aim was to provide the children of the poor with an uplifting education, and benefits to the mothers were overlooked in favour of this grander purpose.

The last quarter of the nineteenth century saw the rise of philanthropic movements in all industrialised countries, particularly in the United States. A myriad of organisations sprang up to assist various categories of people in need, and education, incorporating middle-class ideas about how the working classes should comport themselves, became important as a means of improving the well-being of the poor and socially disadvantaged. Philanthropy was considered a proper activity for women of means. The kindergarten movement can be seen in this context:

The original benefactors looked to the provision of kindergartens for the children of the very poor, as a means of rescuing them from a vicious life-style and of turning them towards the light of Christian living. [4]

But its educational methods, developed by Friedrich Froebel (1782-1852), were not in themselves designed for charitable purposes. Froebel was reacting to the harsh methods and discipline of the German school system. He offered an alternative pedagogy based on the nature of the child, devised 'gifts' or objects for children to handle and study, and saw his methods as leading them into moral behaviour and knowledge of God. Froebel attracted influential female patrons; other women translated his works and provided commentaries on them. Philanthropy and pedagogy combined to form the kindergarten movement.

As the movement spread, it developed another aim. Industrialisation provided new kinds of employment for the women of the working classes, creating what came to be called 'the servant problem'. It was not just that servants were in short supply; there were also widespread complaints about the quality of those available. So it is not surprising that kindergarten methods became associated with training small children in domestic work. This can be seen most clearly in the United States, where there was a flourishing Kitchen Garden Association, aiming to provide training in domestic and household tasks using kindergarten methods.

The early records of the Dunedin Free Kindergarten Association show that the learning of domestic arts such as scrubbing tables and serving afternoon tea was part of the kindergarten programme. The Cohen Report of 1912 (written by Mark Cohen, a long-time supporter of the kindergarten movement in Dunedin) described kindergarten training as the basis of true technical education. The programme was concerned with happiness, work and industry. In 1918, the Wellington Free Kindergarten held an exhibition in the Masonic Hall in Boulcott Street. The first day was devoted to Mother's and Father's work in the home, the chief thought was Industry, and the table work consisted of scrubbing, chopping and stacking kindling, and making bread and milk. The next day the subject was work on the wharf, the next it was farm life and products, and on the final day it was soldiers in camp.

Kindergarten methods were embraced by those looking for a better world, in which social disorder was eliminated and there was a good supply of industrious workers. Many well-to-do women found substitute careers in voluntary service to the free kindergartens, raising subscriptions and proselytising for the movement. They did not, however, intend that their own children or those of their friends and relations should attend a free kindergarten. Such children went instead to the growing number of small private fee-charging kindergartens conducted by young women with kindergarten training. It was not uncommon for the children to be the young relatives of the teacher.

As the free kindergarten movement expanded, it moved beyond the most derelict areas of the cities, and the mothers of the children attending began to share some responsibility for fundraising. In the early days this had been the task of the ladies on the kindergarten committee. However, philanthropic aims did not by any means disappear when the movement became more democratic. Ted (Edna) Scott, who began her training in 1915, recalled: 'When we went into kindergarten work … we had a special feeling about it. We felt we were helping posterity. We felt it was a work of love and that we were doing good.' [5]

In philanthropic movements, one portion of society provided services for another portion. But as the kindergarten movement grew, it ran out of the children of the needy; and the needy often indicated that they did not appreciate being the subjects of patronage. However, a broader group of children was about to be catered for.

Hocken Library, MS-1149/006/001

Children at Rachel Reynolds Kindergarten, Dunedin, c. 1930s. Kindergartens then placed great emphasis on children learning to be tidy, orderly and industrious.

What women are able to do with their lives depends to a large extent on what other women are able to do for them. Despite the emphasis on the mother as the proper person to care for young children, care by servants and family members did not incur public condemnation. This suggests that where a child was cared for was a more powerful factor in the acceptance of various forms of care than who actually carried out that care. Until the Second World War, domestic servants were available to those who could afford them. The 1936 census showed the number of women employed in domestic service as 29,262. In 1945, the figure was 9169; by 1951 it was down to 8731.

The existence of domestic servants was a major factor in the slow early growth of the free kindergarten movement. Once middle-class women could no longer leave their children in the care of someone else in the house, demand for the expansion of free kindergartens grew. In 1941 Inge Smithells, the first organiser for the early playcentre movement, also pointed to the disappearance of servants as one reason for establishing playcentres.

In addition to the committees which established kindergartens, first in the main cities and later in smaller centres, the free kindergarten movement produced several other kinds of women's groups. Mothers' clubs began very early; they were led by the kindergarten director, who arranged speakers on topics such as child health and nutrition. In time, mothers' clubs began running their own affairs and raised considerable sums of money. As their confidence grew, they often came to challenge the decisions of local committees. Mothers' clubs were most successful in the 1950s. By then they had developed as autonomous organisations: they arranged their own speakers, raised money through bazaars and raffles, held shop days, formed drama clubs, organised Christmas parties and performed in annual Talent Evenings, when original skits and choral items were presented by groups from a number of kindergartens.

Post-war kindergarten and playcentre mothers were both responding to much the same social forces. In general they were better educated than their own mothers had been, and looked for new ways of using their talents and abilities, without challenging the ideology of domesticity. By the 1970s, however, mothers' clubs were in decline.

By 1912, the Free Kindergarten Associations in the four main cities had set up training centres for kindergarten teachers; the graduates of each centre also developed their own associations. The New Zealand Free Kindergarten Teachers' Association (NZFKTA), formed in 1954, was the first national teachers' organisation in the field of early childhood care and education. By the 1970s, it was promoting the cause of women in general, and sympathising with the aspirations of the childcare movement, particularly its employees; in 1990 it combined with the Early Childhood Workers' Union to form the Combined Early Childhood Union of Aotearoa. The Free Kindergarten Union and the Playcentre Federation on the whole maintained their opposition to full-day childcare, each claiming to stand for the interests of mothers at home.

Playcentre

The first playcentre opened in St Mary's Church hall in Karori, Wellington, in 1941. Unlike the early kindergarten movement, this new venture was based on self-help and arose first in affluent suburbs. The founders were members of an educational and intellectual elite rather than a business or political elite, and did not set out to raise funds by public subscription. Thirteen of the 14 women who, with two men, signed the 1943 application by the Wellington Nursery Play Centre Association to become an incorporated society were women at home; the only one in paid employment lectured at teachers' college.

English educator Susan Isaacs had inspired New Zealanders when she took part in the New Education Fellowship Conference here in 1937, and her ideas had been stored in the heads and hearts of the playcentre founders: 'It is the conditions of life in the earliest years which most determine the future – whether a child becomes mentally ill or delinquent, or develops into a useful and satisfactory parent and citizen.' [6]

The playcentre movement was not concerned, as kindergartens had initially been, with children's piety and domestic and industrial skills, but with their mental health. As it developed, the movement aimed at nothing less than improving the mental health of the population. It promoted messy play and reflected its intellectual origins by scorning the practice of training children to 'tidy up'. Kindergarten supporters often viewed this as dereliction of duty to a child.

The first playcentres were not seen by their originators as providing a service in competition with kindergartens. An early pamphlet stated:

Of course, the Nursery Play Centre makes no attempt to fulfil the functions of a kindergarten. On the contrary, it aims at fostering the idea that proper provision should be made for the pre-school child, and it is hoped that the idea of the Play Centre will be followed by increased demand for the up-to-date kindergarten. [7]

In 1947 children of varying ages were attending playcentres, kindergarten children among them. There were no regulations banning this practice. The playcentre was a co-operative organisation, and no doubt some mothers of children attending kindergarten in the morning found it convenient to have the child attend an afternoon playcentre as well.

At the time the playcentre movement began, kindergarten teachers worked only half a day. It was envisaged that playcentres might operate in kindergartens or church halls on one or two afternoons, and that a kindergarten teacher might be employed by the group of mothers to supervise the children.

Archives New Zealand Te Rua Mahara O Te Kawanatanga, AAVK 6388 C784

A purpose-built crèche operated on the top floor of the Wellington railway station building between 1937 and 1941. Catering to mothers coming into the city to shop or run errands, it was available to anyone with a train ticket.

Playcentres took children from walking age onwards. Apart from their co-operative nature, they were at first very similar to a shoppers' creche. However, they rapidly developed into something rather different. When afternoon kindergarten was introduced in 1948, kindergarten teachers were no longer available to run playcentre sessions. Playcentre mothers therefore had to train as supervisors, and this proved to be the salvation of the movement: it became an alternative service, rather than paving the way for the establishment of new kindergartens. Playcentre training of women at home opened up opportunities for further training and work, for example as primary school or kindergarten teachers. Because playcentre was publicised as an extension of the family, women could work for it and train for the future without, as it were, leaving home.

Māori Education

Māori women who lived in city suburbs often enrolled their children in kindergarten or playcentre. However, there were large numbers of Māori mothers living in rural and frequently remote areas, with no access to any kind of service outside the whānau for the education and care of their preschool children.

In 1961 the Māori Education Foundation was established. The only woman member of its board of trustees, Miraka (Mira) Szazy, was the nominee of the Māori Women's Welfare League. The foundation's first annual report recorded that it had decided to devote a considerable share of its funds to improving and quickening those factors which encourage intellectual growth in the preschool child, and that it had appointed Mr A. (Lex) Grey preschool officer from February 1963. The development of services was to involve the active co-operation of parents. This story is told in detail in the chapter on Māori women's organisations.

In 1971 a committee of inquiry into preschool education reported that there were 311 recognised kindergartens, 576 recognised playcentres, more than 300 registered childcare centres, 167 private kindergartens, 116 day nurseries, some workplace crèches for the children of students and teachers, and some shoppers' crèches. There were also about 80 family preschools, mainly in Māori communities in the Waikato region.

For many years there had been growing concern among Māori that their language was disappearing. In 1980–81, at a series of tribal hui, the concept of kōhanga reo – language nests – was born. By this time there were hundreds of Māori women with experience of organising some form of early childhood care and education; this extensive experience was brought into the new movement along with the purpose of maintaining te reo. Pasifika women soon adopted a similar model to create Pasifika language nests.

Hutt City Libraries, Evening Post, 26/2/1969

A meeting of Naenae Playcentre at the home of the secretary, February 1969. Five months after its formation, the playcentre had still not been able to find permanent premises.

Daycare and Childcare Services

Childcare, in the form of group daycare, has an ancient history. In nineteenth-century Pākehā society it was provided as a charitable service for the needy, for example for the children of drunken parents. It maintained a philanthropic role longer than the free kindergartens did.

During the 1950s and 1960s women were subject to conflicting social demands. On the one hand, they were supposed to be in the home with their young children; on the other, the economy needed them to work in a range of occupations. In the post-war years, birth cohorts grew very rapidly, creating a matching need for health, education and welfare services. These services had traditionally been staffed largely by women. Suddenly there was an acute shortage of teachers and nurses, and insufficient time to train enough women to meet the demand. However, there were plenty of trained women at home, looking after young children. Soon they were being asked – in fact, begged – by principals of schools and matrons of hospitals to return to work.

For many women, this posed a severe dilemma. Young children were supposed to be irrevocably damaged if their mothers were not with them constantly; yet going back to paid employment offered a much-needed boost to household income, as well as the stimulus of interesting work. But who was going to look after the children?

Suitable workplaces such as schools could often manage the care of a baby, with the help of the older girls. Some women were able to hire part-time help or call on grandmothers – though they too might be out at work. Neighbours were pressed into service too. Yet so-called 'backyard' child-minding arrangements could be unstable and unsatisfactory. Women whose children attended morning kindergarten had some limited time for outside employment; but since the waiting lists were so long, children might not gain entry until they were nearing school age. Playcentres were, on the whole, unsympathetic to mothers who wanted to enrol their children but could not help in the centre.

Yet group daycare, run for profit or not, was unlikely to be the first choice of most women returning to work. There were fears that children would risk infection in group care, and most daycare centres did not offer programmes of the same quality as kindergartens and playcentres. Daycare was tainted with the image of welfare and child neglect, and associated with the idea that it was only for women who had to work, rather than those who chose to do so. This idea was reinforced by the fact that, unlike the other early childhood services, daycare centres were overseen by the Child Welfare Division of the Department of Education.

For all of these reasons, beginning in the 1960s, there was increasing pressure for the government to take greater responsibility for childcare services. Women set out to change the public image of childcare, pointing out that all services for young children contained a component of care and a component of education. However, it was easier to get acceptance – and government funding – for childcare as a welfare service than as a right for women. Any suggestion that employed mothers had a claim on taxpayers' money stirred up all the old arguments about the proper role of women.

This situation changed for three main reasons. First, there were enough working women with dependent children to demonstrate that there was a need. Secondly, the entry of women with dependent children into universities, teacher training, the polytechnics and the senior forms of high schools created a need for suitable childcare. More women began to take up positions on the staff of such institutions; some needed childcare services themselves, or supported them on principle. There was no suggestion that student mothers were socially disadvantaged, and their use of childcare services did not carry the stigma associated with all-day care.

The third catalyst was the programme of activities that took place in International Women's Year, 1975. Childcare was a major concern of the Select Committee on Women's Rights. The funding and oversight of childcare had been moved to the Department of Social Welfare in 1973, when that department replaced both the Department of Social Security and the Child Welfare Division. Women now began a lengthy campaign to return the administration of childcare to the Department of Education.

Both kindergarten and playcentre were single-model services in which there was little variation in basic characteristics from one site to another. Childcare services, on the other hand, tended to operate independently of each other and developed a variety of forms. By the 1970s there were childcare centres run by communities, local bodies, universities, polytechnics and colleges of education, and the Public Service Association had established a centre for the children of public servants. Despite an easier climate of support, women still found it a struggle to keep childcare centres going.

Childcare and the State

The extent to which childcare services are supported by the state is a measure of the gains and losses made by women in achieving social equality. From the 1960s, women had been campaigning for early childhood policies which would remove inequalities in state funding among the various services. The 1976 Conference on Women in Social and Economic Development, which summarised the work of International Women's Year, recommended that the oversight of childcare be returned to the Department of Education and that state funding be made equitable across all early childhood services. Because these services were largely initiated, used and run by women, and their outcomes were difficult to justify in economic terms, they were seldom high on the political agenda. Government funding continued to favour half-day services catering largely for the children of mothers at home.

In 1984, however, the incoming Labour government was committed to reforms which would provide early childhood services of high quality and contribute to equity for women in the workforce and in public life. These reforms were backed by a strong early childhood lobby. In 1986 – 10 years after the International Women's Year recommendation – responsibility for childcare was at last transferred from Social Welfare to Education. In 1988 the training of childcare workers and kindergarten teachers was merged.

Funding, probably the most basic issue, was not addressed until 1987, when the Cabinet Social Equity Committee set up a working group on early childhood care and education, convened by Dr Anne Meade. Both the Meade committee's report, Education to be more (1988), and the government's response, Before five (1988), supported the view that early childhood services of high quality benefited the whole of society, and accepted the need for government intervention to ensure their standards, equity and diversity. Before five recommended a funding increase of 125 per cent over four years to equalise funding between the different services by 1994/5, additional subsidies for children under two, and improved minimum regulations for buildings, staffing ratios and qualifications. Quality was to be assured by means of charters, as with other educational institutions receiving state funding.

In 1989 Cabinet approved funding for Before five's recommendations and the policies began to be implemented. A 1991 independent review of the results of increased funding showed that most of the growth in provision had been in Te Kōhanga Reo and Pasifika language nests, and in services for children under two years. Kindergartens had not yet received funding increases. Playcentres were going to use their increased funding to upgrade buildings and to support women working in a voluntary capacity for the movement. Childcare centres had focused on improving their staffing ratios and training.

Before five faced challenges and opposition from the outset, the policies being clearly at odds with the dominant philosophy of deregulation, user-pays, and minimal government intervention. The National Party was returned to power in 1990, and in a climate of continuing economic difficulties began to review policies on early childhood education. The reasons were partly fiscal and partly philosophical. The National government emphasised the 'core family unit', advocated increased 'family responsibility', and adopted targeted rather than universal social assistance.

The 1991 Budget substantially reduced the subsidy for under-twos and abandoned Before five's staged plan for increased funding. Later in 1991, some of the funds cut from the under-two subsidy were transferred to the Department of Social Welfare, and used to increase fee subsidies to low-income families using childcare or kōhanga reo.

By 1993, women had been banding together in a voluntary capacity to provide education and care for young children outside the home for more than a hundred years. Despite the various barriers they encountered, it should be acknowledged that together they created distinctive educational movements which served young children well, addressed the social problems of their times, and gave many women – Māori, Pākehā and Pasifika – an opportunity for their own abilities and creativity to be recognised and used.

Geraldine McDonald

1994–2018

The political endeavours of the early childhood organisations originally covered in Women together [8] continued through to 2018. Since 1993 they had variously experienced constitutional transformation, name changes and amalgamation; but their mission, although cloaked differently, was ongoing, particularly through their advocacy for affordable, quality ECE for all children. The sector remained significantly the domain of women working on behalf of children, their families and communities. Its status, while much enhanced since 1993, remained low compared with the other education sectors. Gender politics still framed the early childhood landscape.

The featured organisations were not the only institutions shaping the politics of early childhood services, but collectively they remained significant players, at times collaborating to forge and/or protect policy, and sometimes to protest. While cohesive action did sometimes take place across the burgeoning number of early childhood organisations, their philosophical, economic and political divides made this complicated. This essay outlines the broader political context for these endeavours in an era when early childhood policy was shaped and reshaped, more explicitly than in previous decades, by the political philosophies of successive governments.

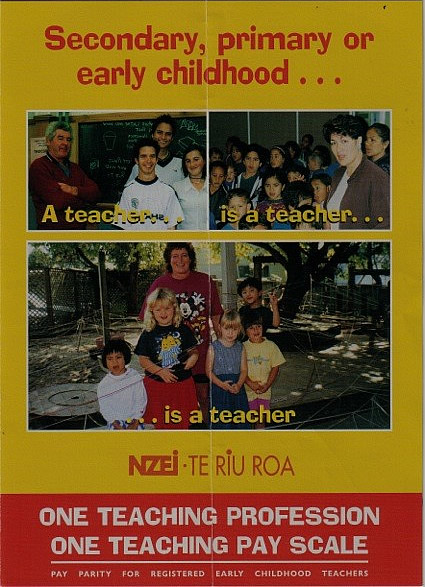

NZEI

NZEI poster seeking pay parity for early childhood teachers.

From 1994, the pattern was broadly one of National terms in government being characterised by caution and culling, and Labour terms yielding policy gains for the sector. However, developments such as the early childhood curriculum Te Whāriki (1996, 2017) were supported across political divides and organisational interests. From 1994 on, the organisations multiplied, the number of services almost doubled, and child participation increased, particularly amongst Māori and Pasifika children and younger children. There was an upswing in qualified teachers, supported by policy that regulated a teaching diploma as the benchmark qualification for licensing. By 2017, 69 per cent of staff held a teaching qualification, including all kindergarten teachers. [9] The balance of early childhood service provision continued to shift in response to social change, with enrolments declining in kindergarten, playcentre and kōhanga reo, and growing in private for-profit childcare (renamed education and care) and home-based services. The changing landscape of early childhood provision had implications for the organisations concerned.

National-led, 1990–1999

Despite National’s 1991 cuts to funding, regulations and qualification requirements, the Before five reforms gave funding gains to playcentre, kōhanga reo and childcare services. However, the benefits to staff, children and families were selective. National removed accountability measures, and rather than lowering fees, employing qualified staff and increasing wages, as had been intended, many private services increased their profits. The political mood had shifted.

The hard-won gains of the flagship kindergarten movement were curbed with the introduction of bulk funding, which ended centralised payment of teachers’ salaries. Regional kindergarten associations had to cut costs, rolls increased, teachers protested, and the umbrella organisation, the New Zealand Free Kindergarten Union, splintered. In 1996 kindergarten teachers were removed from the State Sector Act, absolving the government from negotiating kindergarten salary claims. Despite resulting tensions between the employer associations and kindergarten teachers’ representatives, all campaigned collectively in protest. For staff working in childcare, the introduction of the 1991 Employment Contracts Act had resulted in union coverage being removed. There was turmoil across the sector, causing Carmen Dalli to ask, ‘Is Cinderella back among the cinders?’[10]

Yet several projects had positive outcomes. The early childhood curriculum, Te Whāriki (1996), was achieved through strategic collaboration with a National government and cohesive support across the early childhood organisations. [11] As Sandy Farquhar wrote:

As a first curriculum for early childhood education in Aotearoa, and indeed one of the first internationally, it is remarkable that in an era of right-wing conservatism, the document was able to capture the spirits of feminism, Māori sovereignty, children’s rights and educational theories – at the same time as traversing the path to acceptance. [12]

In 1995 NZEI Te Rui Roa, the primary teachers’ union, by then representing staff in both kindergarten and childcare, began a proactive campaign. Working across the early childhood organisations, but excluding the Early Childhood Council which mainly represented private and corporate childcare interests, it launched the Future directions project in 1996. The collective organisations, led by Geraldine McDonald, argued for universal funding of ECE services equitable with schools; a benchmark teaching qualification, removing lesser childcare qualifications; and a strategic plan for the sector. This campaign marked a political turnaround, with opposition political parties promising they would adopt the report if elected. In difficult times, working ‘together’ was a strategic winner for the community early childhood organisations.

Labour-led, 1999–2008

The incoming government immediately put kindergarten teachers back into the state sector and initiated work on a 10-year strategic plan, with advocacy groups and individuals calling for a new agenda for children and the framing of early childhood policy around children’s rights. [13] A government appointed group, led by Anne Meade, the architect of Before five, and representing all the early childhood organisations as well as teacher education and research expertise, collaborated on developing a strategic plan. Various divides emerged among interest groups, such as non-profit versus privately owned and teacher-led versus parent-led services; but there was also an awareness that a divided sector would halt gains which would benefit children and families.

The 2000s brought the roll-out of the new strategic plan, Pathways to the future: ngā huarahi arataki 2002-2012, with its commitment to quality participation and new funding. This bold move was supported by evidence that qualified teachers were necessary for realising Te Whāriki’s aspiration for all children:

To grow up as competent and confident learners and communicators, healthy in mind, body, and spirit, secure in their sense of belonging and in the knowledge that they make a valued contribution to the world. [14]

The plan was for all staff in teacher-led centres to be qualified teachers by 2012. Funding streams differentiated between teacher-led and parent-led services, such as playcentre and kōhanga reo. The 2004 Budget announced ‘20 hours free ECE’ a week for three- and four-year-olds in community-based centres (although this fell short of earlier demands for a free preschool education as every child’s right). The policy was later extended to private centres and parent-led services, after dismay from parents who saw their children missing out.

New Zealand’s policy directions drew international attention. From the UK, Peter Moss described New Zealand as ‘leading the wave’ of innovation with the development of an integrated approach to funding, regulation, curriculum and qualifications. [15]

In 2008, with an election looming, political commentator Colin James said that Labour ‘may be remembered most lastingly for early childhood education’, which constituted ‘investing in infrastructure, just like building roads. It is arguably Labour’s most important initiative, its biggest idea.’ [16]

National-led, 2008–2017

The incoming government was determined to reduce the cost of Labour’s ‘infrastructure’. The word ‘free’ was immediately removed from the ‘20 hours free’ policy. An economic recession justified retrenchment, and research, training and professional development programmes were culled. The 2010 Budget announced that funding would cover only up to 80 per cent qualified staff. Instead there would be initiatives to improve participation in ‘high need’ locations.

These issues highlighted political divides over funding quality ECE for all children versus targeting funding to those deemed to pose risks. The Early Childhood Council supported moves curtailing the costs of quality. In contrast, kindergarten organisations, determined to protect the employment of their 100 per cent qualified teachers, faced funding shortfalls. An ECE Taskforce established in 2010 excluded full representation of the early childhood organisations, and focused on examining the ‘effectiveness and efficiency of the Government’s current early childhood expenditure’. [17] The Taskforce urged a ‘stepping up’ by the sector, including parents, to take more responsibility with less reliance on the state. Its recommendations proposed a shift from universal funding mechanisms towards targeting so-called ‘priority children’.

The focus on child participation, particularly for four-year-olds, did yield gains, with innovative ECE participation programmes in targeted localities; but there were concerns about the quality of services, due to cuts in funding and qualification requirements. Most early childhood organisations saw the policy context as narrow, and linked to wider government agendas concerning welfare, economic risk and vulnerable children.

Te Whāriki survived the policy shifts, protected by its international acclaim as well as full sector support. In 2014, an Advisory Group was set up. This made recommendations around resources, research and professional development, areas that in earlier times had been culled. A ‘refresh’ was undertaken in 2016, and 2017 saw the launch of an updated Te Whāriki, accompanied by a national professional developed programme. Early fears from the sector that the curriculum might be diminished were mostly allayed.

2018

For most in the early childhood sector, including its organisations and personnel, the mood was optimistic. The new Labour-led government established an Advisory Group for a 10 Year Early Learning Strategic Plan, building on Pathways to the future (2002), with the emphasis on ‘strengthening the sector’, ‘turning the tide’ from profit-focused provision, ‘returning to the principle of free public education’, and ‘limiting the detrimental effects of competition’ between services. [18] This was a bold agenda, but the outcome would depend on the government’s ability to bear the brunt of National’s support of corporate business interests in early childhood provision, and the considerable cost such changes implied.

The early childhood organisations covered here were broadly aligned behind the government’s agendas, and indeed active in crafting its policy directions. While the early childhood landscape had changed since 1993, the broad aspirations and mission in support of women and children were still evident, albeit operating within different institutional arrangements and involving more diverse alliances. There was a collective understanding that jointly brokering sufficient common ground was a necessary precursor for any government action.

Despite many policy gains, the early childhood sector was still defined by one constant reality: that the interests of young children and women had to battle for consideration and funding in the political landscape.

Helen May

Notes

[1] The term 'nursery play centre' was used until 1962, when 'nursery' was dropped. The current term, 'playcentre', was introduced in 1973.

[2] Wood, 1981, p. 7.

[3] Wood, 1981, p. 11.

[4] Dempster, 1986, p. 1.

[5] McDonald, 1975, p. 3.

[6] Quoted in Somerset, 1976 edn, p. 60.

[7] Quoted in McDonald, 1974, p. 154.

[8] NZ Free Kindergarten Union, NZ Playcentre Federation, NZ Childcare Association – Te Tari Puna Ora o Aotearoa, NZ Kindergarten Teachers Association, Early Childhood Workers Union (Employment), Te Kōhanga Reo Trust (Māori).

[9] https://www.educationcounts.govt.nz/statistics/early-childhood-education

[10] Dalli, Carmen, ‘Is Cinderella back among the cinders? A review of early childhood education in the early 1990s’, in H. Manson (ed.), New Zealand annual review of education 1993: 3, Faculty of Education, Victoria University of Wellington, 1994, pp. 223–54.

[11] Nuttall, 2013; May and Carr, 2016.

[12] Farquhar, Sandy, Ricoeur, identity and early childhood, Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Lanham, MD, 2010, p. 150.

[13] Mitchell, 2002.

[14] Ministry of Education, 1996, p. 9.

[15] Moss, Peter, ‘Leading the wave. New Zealand in an international context’, Travelling pathways to the future: ngā huarahi arataki. Early Childhood Education Symposium proceedings 2–3 May 2007, Wellington, Ministry of Education, p. 33.

[16] Colin James, Otago Daily Times, 19 February 2008.

[17] ECE Taskforce, 2011, p. 13.

[18] Ministry of Education, Terms of reference: development of a 10 year strategic plan for early learning, Ministry of Education, Wellington, 2018.

Unpublished sources

Dempster, Dorothy, 'From Patronage to Parent Participation: The Development of the Dunedin Free Kindergarten Association 1889-1939', DipEd thesis, University of Otago, 1986

Finlay, P., 'The History of Tinui Playcentre', New Zealand Playcentre Federation diploma assignment, 1975

Heslop, Jane, 'Early Childhood Care and Education as Social Control: An Examination of the Kindergarten Training Curriculum in Auckland between 1910 and 1990', MPhil thesis. University of Auckland, 1990

Levitt, Phyllis, 'Public Concern for Young Children: A Socio-Historical Study of Reform, Dunedin 1879-1889', PhD thesis, University of Auckland, 1990

Meade, Elizabeth Anne, 'An Organisational Study of the Free Kindergarten and Playcentre Movements in New Zealand', PhD thesis, Victoria University of Wellington, 1978

Wood, Joan, 'The Early History of Playcentre', unpublished ms, 1981, New Zealand Council for Educational Research Library, Wellington

Published sources

Dalli, Carmen and Sarah Te One, ‘Early childhood education in 2002: Pathways to the future’, in I. Livingston (ed.), NZ annual review of education 2002:12, School of Education, Victoria University of Wellington, Wellington, 2003, pp. 177-202

Department of Education, Before five: early childhood care and Eeucation in New Zealand, Department fo Education, Wellington, 1988

Early Childhood Care and Education Working Group, Education to be more (the Meade Report), Government Printer, Wellington, 1988

Early Childhood Education Project, Future directions: early childhood education in New Zealand, NZEI Te Rui Roa, Wellington, 1996

ECE Taskforce, An agenda for amazing children, NZ Government, Wellington, 2011

Gardiner, Crispin, Review of early childhood funding: independent report, University of Waikato, Hamilton, 1991

May, Helen, 'After "Before Five": The Politics of Early Childhood Care and Education in the Nineties', Women's Studies Journal, Vol. 8 No. 2, September 1992, pp. 83-100

May, Helen, Politics in the playground: the world of early childhood in New Zealand, University of Otago Press, Dunedin, 2009 (2nd edn)

May, Helen, The discovery of early childhood, NZCER Press, Wellington, 2013 (2nd edn)

May, Helen, ‘`New Zealand case study: A narrative of shifting policy directions for early childhood education and care’, in L.F. Gambaro, K. Stewart, and J. Waldfogel (eds), An equal start? Providing quality early childhood education and care for disadvantaged children, Policy Press, London, 2014, pp. 147-70

May, Helen, ‘Documenting early childhood policy in Aotearoa New Zealand: Political stories—personal journeys’, in L. Miller, C. Cameron, C. Dalli and N. Barbour (eds),, Sage handbook of early childhood policy, London, Sage, 2017, pp. 151-64

May, Helen and Kerry Bethell, Growing a Kindergarten movement: its people, purposes and politics, Wellington, NZCER Press, 2017

May, Helen and Margaret Carr, ‘Te Whāriki: A uniquely woven curriculum shaping policy, pedagogy and practice in Aotearoa New Zealand’, in T. David, K. Gooch and S. Powell (eds), Handbook of philosophies and theories of early childhood education and care, Routledge, London, 2016, pp. 316-26

McDonald, Geraldine (comp.). An early Wellington Kindergarten as described by Ted Scott, SET, 1, New Zealand Council for Educational Research, Wellington, 1975

McDonald, Geraldine, 'Educational Innovation: The Case of the New Zealand Playcentre', New Zealand Journal of Educational Studies, Vol. 9 No. 2, November 1974

Meade, Anne, 'Women and Young Children Gain a Foot in the Door', Women's Studies Journal, Vol. 6 Nos 1/2, November 1990, pp. 96-110

Ministry of Education, Te Whāriki: he Whāriki matauranga mo nga mokopuna o Aotearoa: early childhood curriculum, Ministry of Education, Wellington, 1996

Mitchell, Linda, ‘Currents of change: Early childhood education in 2001’, in Livingston, I. (ed.), NZ Annual Review of Education 2001: 11, School of Education, Victoria University of Wellington, Wellington, 2002, pp. 123-43

Mitchell, Linda, ‘Shifting directions in ECEC policy in New Zealand: From a child’s rights to an interventionist approach’, International Journal of Early Years Education, 2015, Vol. 23 No. 3, pp. 288-302

M.L.D. [Mary Dobbie], 'Kindergartens Under Fire', Here and Now, June 1952

Nuttall, Joce, Weaving Te Whāriki: Aotearoa New Zealand’s early childhood curriculum document in theory and practice, NZCER Press, Wellington, 2013

Smith, Anne and Helen May, ‘Connections between early childhood policy and research in Aotearoa New Zealand: 1970s-2010s’, in M. Fleer and B. Van Oers (eds), International handbook on early childhood education and development, Springer, New York, 2017, pp. 531-50

Somerset, Gwen, I play and I grow, New Zealand Playcentre Federation, Auckland, 1976