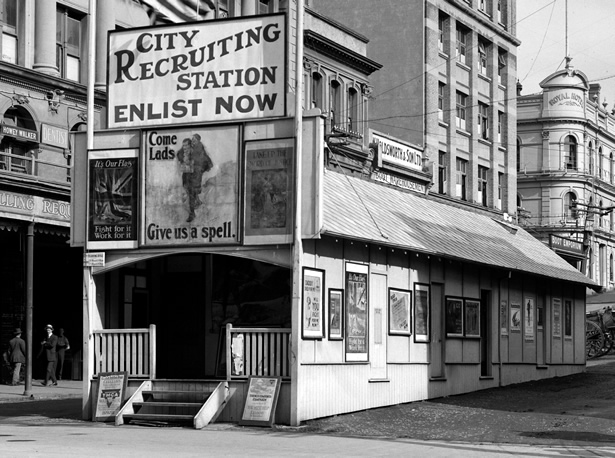

Recruiting men for the New Zealand Expeditionary Force (NZEF) was among the New Zealand government’s most pressing priorities during the four difficult years of the First World War. Tens of thousands were needed every year to keep the NZEF up to strength, and finding them presented major logistical, bureaucratic and tactical challenges to those responsible.

The war’s earliest days saw a great surge of patriotic enthusiasm, and every space in the NZEF was keenly sought after by willing volunteers. As the war dragged on, however, it grew harder and harder to find enough men to keep the NZEF in business. The demand for reinforcements outpaced the number of available volunteers by late 1915, so the government followed the lead of most combatant countries in introducing a conscription system the following year. Though controversial both at the time and since, the system allowed the government to keep the NZEF at full strength up to the close of hostilities. Ultimately some 98,950 people – including 550 nurses – served in New Zealand units during the war years.

Volunteers

New Zealand was well-positioned to contribute to a British expeditionary force when war broke out in August 1914. Three years earlier it had created a Territorial Force which could provide the nucleus of an expeditionary force in the increasingly likely scenario of war breaking out in Europe. The declaration of war brought 14,000 volunteers, many serving territorials, swarming into Defence Department offices across the country to secure their place in the NZEF.

Which unit should I volunteer for?

Men were initially invited to volunteer for a particular arm of service (such as the infantry, artillery or engineers), which enabled them to serve in a unit where their civilian skills might be best utilised. By late 1915 this approach was creating a shortage of men for the infantry, so henceforth all men were required to enlist for ‘General Service’. They could state a preference but the decision would ultimately fall to the Camp Selection Officer at Trentham Camp.

The first 8500-strong group of NZEF soldiers – the ‘Main Body’ and First Reinforcements – left New Zealand in October 1914. Maintaining an orderly and reliable flow of reinforcements would henceforth be the government’s first priority. The Main Body would need to be refreshed with two-monthly instalments of 3000 men to replace those who died or were removed from the forces by illness or injury. Each draft of reinforcements was numbered, with, for example, the 6th Reinforcements sailing in August 1915 and the 28th Reinforcements in July 1917. Each new draft began training as the previous draft prepared to embark for the front.

The forces were organised on a regional basis, with the four military districts of Auckland, Wellington, Christchurch and Otago expected to supply a quarter of each draft. Each regional office initially recorded the names of all those who volunteered, and called upon them when the next reinforcement draft was scheduled to enter camp to fulfil their part of the quota. This ad hoc programme was replaced in February 1915 by a more systematic and centralised process, whereby men could fill out an enlistment card at any post office. They then returned to work and awaited instructions on where and when to formally enlist and be medically examined before heading to camp.

Falling short

The NZEF landed on the Gallipoli Peninsula in April 1915, and the eight-month campaign which followed took a major toll on the New Zealand forces. The military authorities created a string of new units – including a whole new infantry brigade – which expanded the size of the NZEF by 6577 men. These added numbers, combined with the ongoing challenge of replacing the many men who fell in battle, increased the number of volunteers required every month.

News of the Gallipoli landings – and the sinking of the civilian liner Lusitania by a German U-boat which quickly followed – inflamed public sentiment in New Zealand and brought a surge of volunteers to the doors of recruitment offices. Volunteering remained buoyant until the final months of 1915, when the government raised the reinforcement rate from 3000 to 5000 men every two months. The pool of willing volunteers was beginning to dry up, and district quotas began to fall seriously short for the first time.

Press and public railed against the healthy young men who had yet to enlist, accusing them of cowardice and lack of patriotism. The folk-devil of the ‘shirker’ assumed a prominent role in the public discourse about recruitment. In October and November 1915 the government carried out ‘National Registration’, whereby the Government Statistician’s office compiled a card index of all military-aged men across the country and whether or not they were willing to serve. The news that 34,000 eligible men were unwilling to volunteer became a rallying cry for the introduction of conscription.

National Registration had also revealed 110,000 men supposedly willing to volunteer, even though they had yet to respond to the public clamour for men. The government created a Recruiting Board in January 1916 to oversee the personal canvassing of all men of military age across the country in an effort to bring forward the last few volunteers.

The board provided local recruiting committees with lists of all the eligible men in their area, so committee members could hammer on their doors and ask them to volunteer. The scheme failed to bring forward enough volunteers to fill the national quota.

The idea of conscripting the necessary men had entered public debate during 1915, and a vociferous lobby urged ‘equality of sacrifice’ through the conscription of men from across the whole of society. The armies of Germany, France, Italy, Austria-Hungary, Russia and many smaller nations had conscripted men from the outset of the war, with England the only major European combatant to rely solely on volunteers. It too introduced a conscription system in early 1916, followed by the United States and Canada in 1917.

New Zealand’s National Registration programme provided a body of information which could be used as the foundation of a conscription system, and the government slowly moved towards its creation. It gradually passed laws restricting the movements and activities of military-aged men, who from November 1915 were banned from leaving the country without the government’s permission. From February 1916 badges were to be worn by men who had been legitimately exempted from military service, to draw public attention to those who had not enlisted. The noose was tightening around the necks of those who had yet to volunteer.

In May 1916, Prime Minister W.F. Massey introduced a conscription bill based broadly on the English system. Passed on 1 August 1916, the Military Service Act empowered the government to call up any man aged between 20 and 45 for military service at home or abroad, subject to a medical examination and a limited appeals process.

Conscription

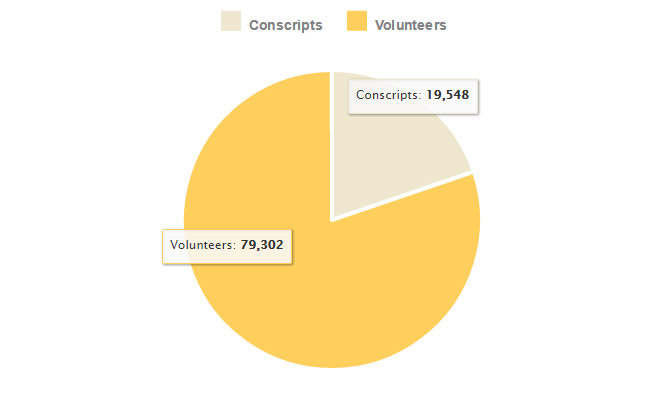

Between 1916 and 1918, 134,393 men were called upunder the monthly ballot system. A further 2876 men were called up under the so-called ‘family shirker clause’, by which the Defence Department could call up the sons of families from which no one had volunteered. It also called up 213 men under section 35 of the Act, by which men found not to have enrolled for conscription could be sent straight to camp without being balloted. This raised the net total of men called up under the conscription system to 138,034. More than half those balloted were rejected as medically unfit or exempted for other reasons, with an estimated 32,270 conscripted men actually being sent to camp. Of these, 19,548 – around 20% of all New Zealand’s First World War servicemen – embarked for the front in 1917 and 1918. Of these, around 80% were volunteers and 20% conscripts

Volunteers and conscripts who embarked for overseas service, 1916-18.

The first monthly ballot was held on 16 November 1916, at the Defence Department’s office in Featherston St, Wellington. It took 20 hours and 15 minutes to draw the 4024 cards. Government Statistician Malcolm Fraser spun two revolving drums containing numbered marbles and drew one marble from each. The first marble’s number directed him to a numbered drawer filled with 500 registration cards, the second to a specific card. All those so selected were now legally in the army, and they were informed by letter within a few days. Men could still volunteer for military service – 24,105 did so between September 1916 and November 1918. The conscription ballot used to fill up the shortfall in each district’s quota.

Director of Recruiting David Cossgrove claimed in early 1919 that ‘the most conspicuous feature of the ballot was the practically whole-hearted acceptance by the people of the justness of the measure.’ The majority of those conscripted accepted the government’s will and submitted to military service, though some evaded, resisted or directly opposed it.

Each man had the right to appeal against his calling-up, with appeals heard by his district’s three-person Military Service Board, usually composed of a magistrate chairman, a farmer and a trade unionist. The appellant could employ the services of a lawyer (about 40% did so), and the government likewise employed a lawyer. Hearings were held in public, allowing their proceedings to be published in the local press. There was no further right of appeal after the hearing, so the boards’ decisions were final. Historian David Littlewood estimates that around 32% of all conscripted men appealed on one ground or another.

The boards could consider exemptions for only a few, tightly defined groups. The vast majority of appellants asked to be excused on the grounds that they performed essential work, or that their absence would inflict great personal hardship on themselves or their families. Employers or unions usually applied for workers to be exempted from military service because they worked in essential industry, and from 1917 the government issued guidelines on which industries were considered essential and which were not. From early 1917 the boards could also appoint trustees to manage soldiers’ businesses while they were away. The boards often struggled to make judgments on personal hardship appeals, so the government made financial provision for soldiers’ families in order to free breadwinners from household responsibilities. No group was categorically exempted from military service, though appeals from members of the clergy and theological students were generally adjourned sine die (suspended indefinitely), which amounted to the same thing.

Littlewood estimates that 4.8% of all appeals were made by men seeking exemption on philosophical, ethical, or religious grounds (conscientious objectors). The Military Service Act permitted the Military Service Boards to exempt men on religious grounds, but only if they were an accredited member of a recognised pacifist sect. Only 73 men were exempted on religious grounds, though others willingly joined non-combatant units such as the Medical Corps or the Army Service Corps where they would not have to bear arms. Some conscripted men refused any form of military service, and 286 such men were court-martialled and sentenced to terms of imprisonment. Read our main feature on conscientious objectors and dissent.

The government recognised that the key to making conscription work lay in punishing those who tried to evade the system. Under the Military Service Act, balloted men who failed to present themselves for service could be imprisoned with hard labour for up to five years, and employers could be prosecuted for hiring them. In February 1917 the Defence Department created a Personal Service Branch which investigated all such cases and issued arrest warrants for absconders. By March 1919 it had investigated 10,737 men, of whom 1294 remained at large. Of those located, 2211 had been found to be eligible for service, 580 had been arrested for breaches of the Military Service Act and 1133 warrants were outstanding. Ultimately, 2320 men were deprived of their civil rights for 10 years for deliberately avoiding military service.

Medical examinations

Each recruit had to pass a basic medical examination before being accepted into the NZEF. Doctors or military medics inspected each man, ensuring they had good hearing and eyesight, a ‘well formed’ physique, a healthy heart and lungs, good teeth, that they were not afflicted by illness or fits, and that they were free of hernia, varicose veins or varicocele (testicular varicose veins), haemorrhoids and skin disease. The inspecting physician decided whether the man was in ‘good bodily and mental health’ and gave him a medical classification:

| A | Fit for active service beyond the seas |

| B1 | Fit for active service beyond the seas after operation in Camp or Public Hospital |

| B2 | Fit for active service beyond the seas after recovery at home |

| C1 | Likely to become fit for active service after special training |

| C2 | Unfit for active service beyond the seas but for service of some nature in New Zealand |

| D | Wholly unfit for any service whatever |

In the voluntary era recruits were inspected either by their local doctor or, increasingly, by an army doctor connected with their local Defence Department office. The first phase of their enlistment process involved being called to their local drill hall for inspection on a certain date, along with the other men of that reinforcement draft. By late 1915 recruiting offices had been opened in the four main centres, with a doctor always available to inspect men when they enlisted.

By 1916 the Defence Department was growing concerned that pressure on army doctors was allowing men to evade service by feigning illness or injury. With the introduction of conscription late that year, the department created a network of Medical Boards to inspect the recruits consistently and methodically. The boards travelled around the districts after each ballot, inspecting up to 60 men a day.

Henceforth balloted men were called to their local drill hall on a certain date. They filled out their attestation form and made the oath of allegiance before going into an adjoining room and stripping off their clothes. They then went into the medical examination room wearing only a jacket and carrying their inspection paper, which gave their military number but not their name. The board then inspected the man without knowledge of his identity. Cossgrove noted that it was often an unpleasant job for the medical officers, ‘working on a hot summer’s day amid a crowd of undressed, over-heated recruits whose last bath had been taken days, at least, prior thereto!’

Age, height and weight requirements for the NZEF, 1914–18

The age and height requirements for new recruits changed during the war in response to the ever-increasing demand for more soldiers.

| Age | |

| August–October 1914 | 20–35 years |

| October 1914–October 1915 | 20–40 years |

| October 1915–July 1917 | 20–45 years |

| July–September 1917 | 20–44 years |

| September 1917–November 1918 | 19–44 years (19-year-olds required permission of parents) |

| Height | |

| August 1914–October 1915 | Over 5ft 4in (1.62m) |

| October 1915–November 1918 | Over 5ft 2in (1.57m) |

| Weight | |

| August 1914–November 1918 | Under 12 stone (76.2kg) |

The later days of recruiting

The Defence Department divided the eligible men, known as ‘reservists’, into several ‘divisions’, each of which was to be exhausted before the next was called up. Balloting began with the First Division, single men without wives or children, in November 1916, and moved on to Second Division men (married but childless) in October 1917.

The rules were amended and tightened in mid-1917 as the supply of unmarried men ran out. The district quota was abolished in September 1917, after which the conscription ballot filled national rather than local shortfalls. All Second Division ballots drew recruits from across the country. Young men were now allowed to volunteer at 19 with their parents’ permission; if they did not, they were called up automatically within a month of turning 20. Other men were allowed to volunteer only if their group of reservists was currently being balloted. Men from earlier groups who presented themselves later were expected to proceed directly to camp under threat of arrest.

By late 1917 the supply of single men without dependants was all but exhausted, with the exception of the approximately 500 young men who turned 20 each month. The Defence Department toiled to expand its catchment of eligible single men, to hold off conscripting men with dependants for as long as possible. It created a ‘Home Service’ branch consisting of men physically incapable of overseas service, but who might be placed into essential work at home to allow other men to be sent abroad. It also operated dental clinics at camps to reduce the number of men rejected with bad teeth, and funded minor operations in order to pass men who fell just short of medical fitness. In November 1917 it converted Tauherenīkau training camp into a ‘C1 Camp’, where men who narrowly failed their medical examinations might be brought up to an acceptable state of fitness and reclassified as ‘fit’. Despite these efforts, married men with one child were called up from April 1918 and men with two children from June.

Shortfalls in Māori units in France saw conscription extended to Māori in late 1917 and the first ‘Maori ballot’ conducted in May 1918. The government limited the ballot to the Waikato district, which had produced few volunteers. Minister of Defence James Allen was motivated by a belief that all sections of the community should be forced to play their part, but Waikato Māori resisted enlistment because of historical grievances going back to the land confiscation of the 1860s. When only a few of the 552 conscripted Māori presented themselves for military service, a raid on Te Paina marae in Mercer saw 14 men arrested and imprisoned. The war ended before any of the Waikato conscripts could be sent overseas. Read our main article on Māori conscription.

The disbandment of the 4th Infantry Brigade in France in early 1918 and the resulting drop in the number of reinforcements needed eased the pressure in New Zealand slightly, and the number of men balloted dropped each month after June 1918. The final ballot was conducted on 12 August 1918, with all remaining men in the earlier ballot divisions called up on 9 September and 10 October.

By the time of the Armistice in November 1918, New Zealand had supplied 98,950 recruits to the British war effort (in addition to 9924 in camp at the close of hostilities and those who served in other Imperial units). Of these, around 72% were volunteers and 28% conscripts. Around 9% of New Zealand’s total population was recruited for service in the NZEF.

Non-Māori ballots under Military Service Act, 1916–18

| Ballot No. | Ballot dates | Number called up | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First Division | Second Divison Class A | Second Divison Class B | Second Divison Class C | Total | ||

| 1 | 16–18 November 1916 | 4024 | 4024 | |||

| 2 | 11–12 December 1916 | 2886 | 2886 | |||

| 3 | 8 January 1917 | 3514 | 3514 | |||

| 4 | 5–6 February 1917 | 6581 | 6581 | |||

| 5 | 5–6 March 1917 | 4311 | 4311 | |||

| 6 | 10–11 April 1917 | 4573 | 4573 | |||

| 7 | 1–2 May 1917 | 8066 | 8066 | |||

| 8 | 29–30 May 1917 | 8001 | 8001 | |||

| 9 | 26 June 1917 | 7588 | 7588 | |||

| 10 | 21–23 August 1917 | 14050 | 14050 | |||

| 11 | Remainder of division, 24 September 1917 | 8320 | 8320 | |||

| 12 | 26 October 1917 | 1410 | 4627 | 6037 | ||

| 13 | 26 November 1917 | 698 | 4828 | 5526 | ||

| 14 | Remainder of division, 18 December 1917 | 822 | 3494 | 4316 | ||

| 15 | Remainder of division, 14 February 1918 | 978 | 255 | 1233 | ||

| 16 | Remainder of division, 19 March 1918 | 486 | 78 | 564 | ||

| 17 | 13–17 April 1918 | 514 | 35 | 9769 | 10318 | |

| 18 | Remainder of division, 12 May 1918 | 509 | 33 | 7559 | 8101 | |

| 19 | 10–11 June 1918 | 490 | 38 | 57 | 9816 | 10401 |

| 20 | 16 July 1918 | 574 | 32 | 36 | 4936 | 5578 |

| 21 | 12 August 1918 | 434 | 23 | 30 | 4912 | 5399 |

| 22 | Remainder of division, 9 September 1918 | 507 | 13 | 12 | 3874 | 4406 |

| 23 | Remainder of division, 10 October 1918 | 540 | 14 | 8 | 38 | 600 |

| TOTAL | 16 November 1916 - 10 October 1918 | 79876 | 13470 | 17471 | 23576 | 134393 |

Key:

First Division: single men without dependants

Class A, Second Division: married men without children

Class B, Second Division: married men with one child

Class C, Second Division: married men with two children

Note:

Anticipating that many men would be rejected on medical or other grounds, the department called up three or four men for each vacancy in the reinforcement draft. On six occasions the government called up all the remaining men in a reservists’ group without holding a ballot, when that group was on the brink of being exhausted.

Sources

Return showing the number of reservists compulsorily called up under the Military Service Act 1916, IA1 1652 29/125; Calling up notices for ballot 23, NZ Gazette, 1918, pp. 3513-20.

Attached documents

Recruiting 1916–18

David Cossgrove, Report on conscription, 1916–18, November 1919 (pdf, 38mbs)

Director of Recruiting David Cossgrove wrote this assessment of recruiting under conscription in March 1919. It includes a detailed overview of how the scheme operated, recruiting circulars explaining the day-to-day working of the system, and some useful statistics.

Reference:

Archives New Zealand/Te Rua Mahara o te Kāwanatanga

Wellington Office

AAYS 8638 AD1/712 9/169 pt 2

Fraser report

Malcolm Fraser, ‘War work of the Census and Statistics Office’, November 1919

Government Statistician Malcolm Fraser compiled this potted history of the wartime conscription process from the perspective of those responsible for administering it. It provides many useful clues to how the process was undertaken, and complements the Defence Department perspective provided by the Cossgrove report. It includes a table of figures outlining the number of men called up in each ballot, though it omits the men called up in the 23rd ballot in October 1918.

Reference:

IA1 box 1652 29/125, Archives New Zealand

Provision and Maintenance

Title: New Zealand Expeditionary Force: its provision and maintenance (pdf, 20 mbs)

Published in February 1919, Provision and maintenance is the most detailed statistical overview of the military side of New Zealand’s First World War experience ever published. It provides a snapshot of the Defence Department’s knowledge at the end of the war, although some of the figures would be revised over the next few years. Read our feature on First World War statistics

This copy was held at the Defence Department’s head office, and the handwritten annotations reflect the process of amendment which followed its publication.

In 1922 the British War Office published a similar book covering the whole British Empire, Statistics of the military effort of the British Empire during the Great War 1914–1920, which can be downloaded here: https://archive.org/details/statisticsofmili00grea.

Provision and maintenance graphs (not in main pdf above)

- NZEF: dates of training camps, dates and strengths of mobilisations and embarkations, periods of training, and numbers in camp at any date

- NZEF: establishment of New Zealand Division and New Zealand Mounted Rifles, strengths of reinforcement drafts, and percentage rate of reinforcement

- NZEF: percentage of the total population and of the male population of military age mobilized and embarked

Reference:

Archives New Zealand/Te Rua Mahara o te Kāwanatanga

Wellington Office

AAYS 8666 AD37/23/33

Further information

This article was written by Tim Shoebridge and produced by the NZHistory team in 2016. A fully footnoted version is available to download as a pdf here.

- Paul Baker. King and Country call: New Zealanders, conscription and the Great War, Auckland University Press, Auckland, 1988

- Imelda Bargas and Tim Shoebridge, New Zealand’s First World War heritage , Exisle, Auckland, 2014

- David Cossgrove, ‘Recruiting 1916-1918’, 31 March 1919, AD1 712 9/169 pt 2, Archives New Zealand

- John M Graham. ‘The voluntary system: recruiting 1914-16’, MA thesis, University of Auckland, 1971

- David Littlewood, ‘The tool and instrument of the military? The operations of the Military Service Tribunals in the East Central Division of the West Riding of Yorkshire and those of the Military Service Boards in New Zealand, 1916-1918’, PhD thesis, Massey University, 2015

Website

- Conscription, conscientious objection and pacifism, an entry on Te Ara.

Community contributions