New Zealand has a long history of trying to protect its natural environment from exotic pests and plant and animal diseases, and some of the strictest quarantine laws in the world.

Quarantine officers first began checking imports at ports on a significant scale in the 1890s and their role expanded dramatically after the Second World War. By then quarantine authorities were monitoring the arrival of everyone and everything entering the country, whether by ship or by aircraft. Deregulation from the 1980s prompted a more strategic and nuanced approach.

The earliest arrivals

Sharing no land borders with other nations, New Zealand is one of the most isolated places on Earth, safer than most countries from unwanted diseases and pests. Its plants and animals existed in seclusion for millions of years, though wind and sea currents have blown birds, insects, marine life and seeds here. Polynesian voyagers, arriving around 700–800 years ago, brought food plants such as kūmara, yams, taro and gourds, along with the Pacific rat (kiore) and the Polynesian dog (kurī). The Māori colonists rapidly changed the native ecology of the islands, deforesting around 30 per cent of the landscape and hunting many bird species to extinction.

Biocontrols

Stoats, ferrets and weasels were a bad idea but biological control through natural enemies is now widely practised to control the spread of unwanted insects and fungi. It is an environmentally useful alternative to chemicals, which are costly, can have unwelcome side effects and can lose their effectiveness as targets develop resistance. Biological control agents include predators, pathogens (disease-causing organisms) or parasitoids (which infect and kill their prey). Many countries now practice integrated pest management, combining biological control agents with judicious use of chemicals. New Zealand has released about 60 biocontrol agents to date.European visitors accelerated this process of change from the late eighteenth century onwards, starting with the release of pigs, goats and sheep by James Cook’s crews. Soon Māori were enthusiastically growing potatoes and herding pigs to trade with Europeans for muskets and other desirable commodities. The settlers who flooded into the country from the 1840s introduced a wide variety of plants and animals. The settler economy depended on growing things to feed itself and to provide some export income. European settlers were intent on carving farms out of the bush, which involved importing livestock and grass seed in order to maximise stock yields, as well as birds and ornamental plants to make the new land seem more familiar.

Settlers introduced livestock such as cows and pigs, crops such as wheat, and fruit such as apples and pears. They also sowed English grasses, planted British trees, released British birds, and introduced hunting game such as deer, rabbits, and fish. Some species were introduced to control other imported species; weasels and stoats to control the rabbit population, and small birds to eat imported caterpillars. These soon became pests in their own right, and some imported garden plants became noxious weeds which choked native species. Other pests came in accidentally, including the Norwegian black rat, British slugs and snails, clothes moths, thistles, fleas, and houseflies.

Early years of plant and animal quarantine

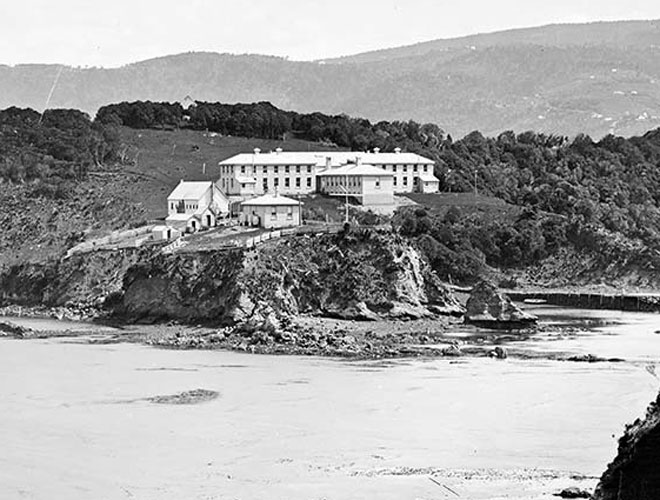

Alexander Turnbull Library, 1/2-003221-G

Quarantine Island, Otago Harbour (see full image and caption).

At first the European settlers gave little thought to what they were planting or shepherding and there were no restrictions on what people could bring in. It gradually became clear that some of their plants and animals had become pests which threatened their livelihoods, or carried smaller pests or diseases which could cripple the nascent agricultural and horticultural industries.

Settler governments began passing measures to protect livestock from pests and diseases in the 1840s. An 1849 ordinance required that all livestock arriving in New Zealand be checked for the mite ‘sheep scab’ by sheep inspectors, and successive inspection laws saw the mite eradicated from New Zealand by 1893. An 1861 Act allowed provincial governments to ban diseased cattle from their districts, and from 1876 diseased livestock could be prohibited from entering the country.

Plant quarantine was introduced more slowly, beginning with a Nelson Provincial Council ordinance requiring the detection and destruction of American Blight in 1854. The Codlin Moth Act of 1884 introduced the first nationwide measure, requiring Customs officers to ensure that imported fruit was free of the pest before it was unloaded. The Act was ineffective, and attempts to strengthen it by penalising orchardists who neglected to keep their trees pest-free met with little success.

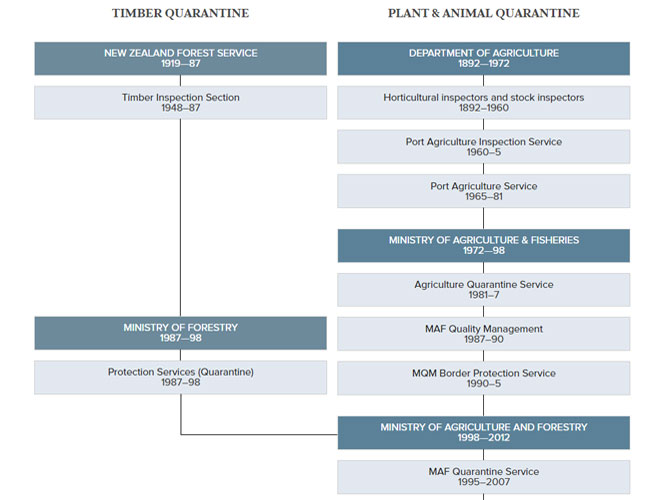

Adapted from Gavin McLean and Tim Shoebridge, Quarantine! Protecting New Zealand at the border, Otago University Press, Dunedin, 2010

Plant and animal quarantine timeline (see full timeline and caption).

In 1892 the Liberal government created the Department of Agriculture, tasking it with protecting New Zealand’s livestock industry. Refrigerated shipping had created a lucrative trade for New Zealand meat and dairy products in Britain, but continued success in this market would depend on the country’s exports meeting a high standard. The Liberals passed the Orchard and Garden Pests Act (1896) and the Noxious Weeds Act (1900), and these acts (together with their subsequent amendments) enabled the department to block the entry of diseased or infested plants at New Zealand ports or their distribution within the country. From 1899 the department built fumigation chambers at the main ports, where imported plants could be gassed to kill any insects hiding in them. The Stock Act (1893) empowered the department to quarantine all live animals arriving in New Zealand to check them for disease, and gave it broad powers to destroy any diseased stock found on New Zealand farms.

The department’s livestock and horticultural inspectors took over inspection work from the Customs officers who had previously carried out quarantine inspections. Before being released to their importers, livestock and live plants were sequestered at secure quarantine grounds to see if pests emerged or diseases developed. The horticultural inspectors inspected imported fruit at the wharf, gradually refining their processes. They met with occasional resistance from importers wishing to speed up the process, and their restrictions on imported produce sometimes played into tariff wars with Australia.

The aviation age and 'disinsection'

Border security challenges multiplied after the Second World War. Before then all people and cargo arrived by ship. In the case of the main trade route between Britain and Europe, ships generally came from well-regulated markets and for most of their voyages sailed through cool or temperate latitudes in weather chilly enough to kill off most pests. Threats still existed, such as termite infestations and those posed by barked timber and dunnage (low-quality timber carried by ships to secure cargo), but officials considered the risks manageable.

From the late 1930s, the growth of long-distance commercial aviation changed this picture Airlines set up new services, first with seaplanes and then with land-based planes. An insect could survive a short plane trip much more easily than a voyage. Aircraft kept getting bigger, faster and – even more critically – more attractive to insects. Pre-war experiments in the Northern Hemisphere had shown that live insects and their eggs could easily survive plane journeys. In a 1946 experiment, the Royal New Zealand Air Force flew caged mosquitoes from Japan to Whenuapai. Many of the insects survived and were fit enough to reproduce in a northern summer.

© Pia Scanlon, Western Australian Agricultural Authority, 2019

Mediterranean fruit fly (See full image and caption here).

A new risk had appeared in 1944 when US ships returning from Pacific battlegrounds accidentally introduced the destructive oriental fruit fly, Dacus dorsalis (now known as Bactrocera dorsalis), to Hawaii. Co-operation between the US Navy and New Zealand authorities had prevented the flies from being brought to New Zealand by sea, but aircraft were a different story, since planes en route from North America had to land at highly infected Honolulu. New Zealand, like Australia, paid the US Department of Agriculture to spray aircraft. The practice of spraying planes with insecticide (‘disinsection’) gained currency after the war and the Department of Agriculture moved to spraying on arrival. They also inspected every aircraft arriving from overseas at a local ‘sanitary aerodrome’ (these then included seaplane landing bases).

The post-war decade saw health and agricultural authorities racing to keep up with a new transport industry that was quite literally taking off. Half an hour before landing passengers were sprayed with pyrethrum-DDT aerosol insecticide. Once they left the aircraft it received a more thorough treatment – 95 seconds on average for a 75-seater Lockheed Electra. At first aircrew sprayed their planes (‘blocks away’, and/or en-route, known as ‘top of descent’), but after a few years Agriculture accepted World Health Organisation (WHO) advice to spray the planes themselves on arrival, before the passengers disembarked (known as ‘On-blocks’). Eventually airlines adopted this practice, although most passengers viewed it as a government requirement.

The practice of spraying passengers seated on aircraft ended in the 1980s. Ministry of Agriculture and Fisheries (MAF) scientist Pat Dale pushed for trials of a new synthetic insecticide called permethrin, which would allow an aircraft’s internal surfaces to be treated while it was in a hangar for maintenance. The trials proved successful, and Air New Zealand adopted ‘residual treatment’ with permethrin shortly afterwards. Dale emphasised that the chemical was not toxic to people, estimating that a passenger would have to lick the entire inside of a jumbo jet, carpet included, to experience any ill-effects.

The modern quarantine system emerges

Archives New Zealand, NPS AANR 632.94 34/14/4

Post office inspections (See full image and caption here).

In 1952 the Plant Quarantine Regulations introduced the basic formalities that are still with us: declaration forms and the inspection of baggage, cargo and the aircraft itself. Quarantine inspectors took a growing interest in the items international passengers carried with them on arrival, particularly small quantities of potentially-infested fruit, meat which might harbour animal disease, and larger items (such as cars, furniture and ornaments) which might conceal pests or soil carrying disease. Inspectors also inspected packages at post offices, looking for parcels containing foodstuffs or plants.

The inspectors struggled to meet the ever-growing demands of expanding passenger travel and bulk cargo importing. Airport work increased exponentially, and there was pressure on the inspectors to interview passengers and spray planes as quickly as possible. The challenges of the aviation era led to the formation in 1960 of the Port Agriculture Inspection Service a stand-alone quarantine service which placed all the country’s inspectors under centralised management for the first time and initiated two decades of development and growth which produced the modern border inspection system.

YouTube: Archives New Zealand

Forbidden fruit! Department of Agriculture film, 1950s (See video and caption here).

Most ‘quarantine officers’, as the inspectors became known, worked in one of the four main centres and rotated between duties at ports, airports and post offices. Quarantine officials recognised that food carried by passengers posed the greatest risk of introducing pests and disease, so international passengers were directed to an ‘Agriculture’ lane at the Customs checkpoint if they had anything to declare. Quarantine officers ensured that dirt was scrubbed from shoes, that imported food was inspected and if necessary safely disposed of, and that risky items were fumigated or incinerated.

A quarantine officer inspected every arriving ship, checking offloaded cargo for insects and ensuring that no foreign food left the vessel. The officer sealed the ship’s meat locker and made sure that ‘gash’ (garbage) bins were securely covered to prevent seagulls dropping food scraps ashore. Post office duty saw the international mail squeezed, shaken, sniffed and listened to; suspicious packages were opened and scrutinised. Imported vehicles were winched into the air to let quarantine officers hose foreign dirt from their wheels and chassis.

Ministry for Primary Industries

Foot-and-mouth disease in a dairy cow in Africa, February 2012 (see full image and caption).

The quarantine service watched international developments in plant and animal health closely, and maintained risk profiles on countries on the basis of information supplied by the WHO and other international watchdogs. The dual fears of foot-and-mouth disease and fruit-fly outbreaks drove much of the service’s work, reflecting its emphasis on preserving the viability of the country’s agricultural and horticultural sectors.

Professionalisation and growth dominated the quarantine service’s first two decades. It now preferred its staff to have relevant qualifications rather than just a rural background, and to speak more than one language to help communicate with passengers and crews who spoke little or no English. In the late 1960s the first female quarantine officers were appointed.

Ngā Taonga Sound & Vision, TZP46999

Segment from Agreport television programme about New Zealand's agricultural quarantine system in 1986 (see full video and caption).

Checking passengers and imports took time and could create tension, since security and speed were often at odds with each other. The quarantine service resisted several attempts to combine Customs and quarantine checks into a single role, arguing that this would reduce the country’s safeguards against ecological disaster. It has remained a politically-charged issue.

New Zealand’s changing patterns of trade brought new challenges. In the early 1960s Britain took just over half of New Zealand’s exports. By the early 1970s the proportion had fallen to just over a third, and it would keep shrinking. Trade with Australia and North America grew, but ever more ships now came from Asia (Japan especially) and other new places, posing more exotic pest and disease threats.

The switch to shipping containers in the late 1960s also changed the nature of the quarantine challenge. Containers made shipping cheaper and faster, but unfortunately pests liked these big boxes, which were warmer and drier than the holds of older ships.

Deregulation, 'biosecurity', and trade tensions

Ministry for Primary Industries

International trade in endangered species (See full image and caption here).

The deregulation of the public service and shifting management philosophies brought major changes to work at the border during the 1980s and 1990s. The old Ministry of Agriculture and Fisheries (MAF) bureaucracy was dismantled and the quarantine service underwent a succession of structural changes as it moved into the user-pays era. Formerly free fumigation and inspection services now cost importers money, and labour-intensive compliance services were moved to 'user pays' cost recovery principles.

At the same time the focus of political debate on quarantine issues was slowly shifting. Environmentalism was gaining traction at the political level and influencing public debate and policy to an unprecedented degree. The Biosecurity Act (1993) extended the purpose of border protection from the old preoccupation with agriculture, horticulture and exotic forestry to protecting the country’s natural environment. Organisms that would harm New Zealand’s ‘biodiversity’ would be resisted as strongly as those which could threaten access to international markets.

Visit our quarantine heritage

Island-based quarantine stations began with human ‘clients’ but went on to serve other purposes, plant and animal quarantine, defence and harbour infrastructure. The stations grew in number and some may be explored today. The main ones are:

- Motuihe Island (Auckland)

- Matiu/Somes Island (Wellington)

- Quail Island/Otamahua (Lyttelton)

- Quarantine Island/Kamau Taurua (Otago)

The emphasis on ‘biosecurity’ came at a time when the quarantine service was being forced to move more and more into risk-assessment analysis and away from physical inspections of imported plants and animals. The General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade 1994, which emphasised reducing domestic price subsidies and trade barriers, moved to establish more trade-friendly quarantine measures. This accelerated the quarantine service’s move towards a risk-analysis model, because to be compliant it had to base its inspection practices on transparent, scientifically-defensible practices acceptable to trading partners.

These pressures saw the government shift more responsibility for inspections to importers and overseas officials, and confine itself to searching only a small sample of imports. Not everyone was happy with this. Environmentalists complained that these trade-driven practices opened the natural environment to serious risk. MAF responded that a ‘zero-risk’ policy, with everything manually searched, was no longer politically acceptable or logistically possible. Priorities would be determined by statistical modelling and technological innovation.

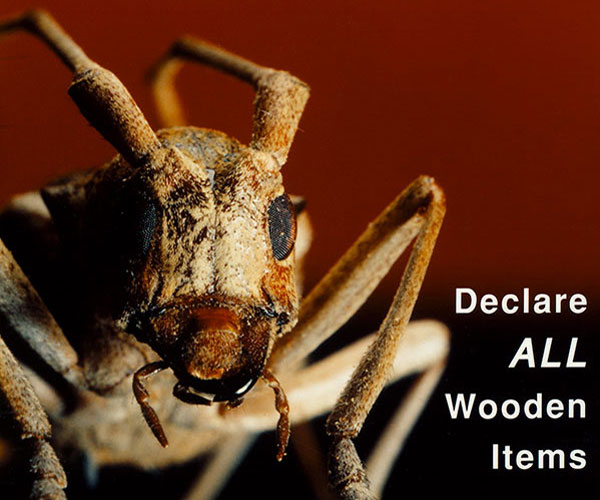

The ever-increasing number of shipping containers entering the country put growing pressure on the quarantine service. Under-staffed and under-funded, it tried to categorise risk levels and inspect only the riskiest boxes at the wharf. In 2000 public reaction to the discovery of four live snakes in separate containers brought a rethink. Three years later MAF (now the Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry) issued a new container standard and certified suitable major importers to create off-wharf transitional facilities, significantly increasing the border protection firepower. By 2004 it had accredited 12,000 people to unpack containers at 5000 facilities, massively expanding the border security force. Earlier it had launched a website to advise overseas travellers about banned items.

YouTube: Ministry for Primary Industries

Brown marmorated stink bug (See video and caption here).

Several outbreaks in the mid-1990s raised the profile of quarantine in the public domain. Outbreaks of Mediterranean fruit fly in 1995–6 saw New Zealand fruit banned from several overseas markets for more than a year, while an outbreak of white-spotted tussock moth in 1996 caused widespread concern. MAF and the then Ministry of Forestry launched major programmes to manage these incursions and gradually eliminated the insects.

These incursions prompted Cabinet to allocate around $20 million to the strengthening of the country’s quarantine work, allowing the purchase of X-ray machines to help inspect baggage at airports and international mail. It also facilitated the development in 1996 of a detector dog programme which trained beagles to sniff passengers and baggage for food items. By one estimate this pushed the detection rate up from about 55% to 85–95%.

Further information

This article was written by Tim Shoebridge and Gavin McLean and produced by the NZHistory team. It was commissioned by the Ministry for Primary Industries.

Books

- Jaimie Baird, Quarantine inspected: the work of front-line quarantine inspectors in New Zealand’s biosecurity system, Primedia, Wellington, 2012

- Joan Druett, Exotic intruders: the introduction of plants and animals into New Zealand, Heinemann, Auckland, 1983

- Gavin McLean and Tim Shoebridge, Quarantine! Protecting New Zealand at the border, Otago University Press, Dunedin, 2010

Links

- Acclimatisation (Te Ara)

- Beekeeping (Te Ara)

- Biosecurity (Te Ara)

- Biosecurity New Zealand (Ministry for Primary Industries)

- Conservation – a history (Te Ara)

- Government and agriculture (Te Ara)

- Insect pests of crops, pasture and forestry (Te Ara)

- Marine invaders (Te Ara)

- Weeds of agriculture (Te Ara)

Community contributions